Last October, I watched a former environmentalist from Suffolk, England Chrissie Wellington, a cheerful woman whose friends call her Muppet win the Hawaii Ironman. None of the experts on the Kona course had ever heard of her, and when she took the lead after the halfway point, we assumed she would blow up. Upstarts aren’t supposed to have a prayer in Hawaii, but Wellington owned the race, finishing the 2.4 miles of ocean swimming, 112 miles of biking, and 26.2 miles of running in 9:08:45, five minutes ahead of the next-fastest woman, Samantha McGlone.

Chrissie Wellington biking

Hawaii Ironman champion Chrissie Wellington on the road

Hawaii Ironman champion Chrissie Wellington on the roadReto Hug

Team TBB's Reto Hug fueling up

Team TBB's Reto Hug fueling upBrett Sutton

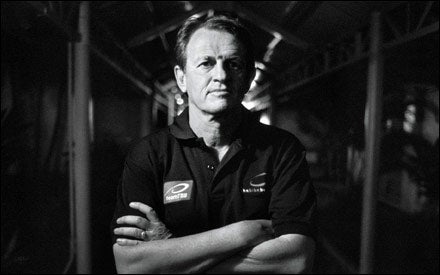

Sutton at the track

Sutton at the trackJustin Granger

Triathlete Justin Granger on a break in the pool

Triathlete Justin Granger on a break in the poolAt a press conference that evening, we learned that Wellington had quietly raced and won her first Ironman, Ironman Korea, seven weeks before Hawaii, a decent feat but nothing compared with a victory at the Ironman world championship. Equally mystifying was the fact that she’d been a pro, training seriously, for only nine months.

At one point during all this, Wellington took a moment to thank her coach, who wasn’t there but whose name was very familiar to people in the know: Brett Sutton. And with that, the reaction to her win shifted from “How did this happen?” to “Oh.” Since then, she’s proved it was no fluke. Earlier this year she won Ironman Australia and Ironman Germany. Returning to Kona on October 11, she’s a favorite to defend her title in triathlon’s greatest event.

SUTTON IS A 49-year-old Australian who’s been building top triathletes for almost 20 years, among them Wellington, Loretta Harrop, Greg Bennett, and several others. In disciplines both long and short, his pupils have won some 15 world championships and two Olympic medals. He’s widely considered the best, and most unorthodox, coach in the sport.

Sutton is shamelessly at odds with trends in modern-day triathlon. Most of his peers hold exercise-science degrees, still compete themselves, and love technologies like power meters and heart-rate monitors. Sutton is a high school dropout who never ran a triathlon and has no respect for gadgets. He says they’re pointless in a pursuit as purely aerobic as triathlon. Instead, he draws on the performance fundamentals he learned during his early days as a swim coach and as a trainer of racehorses and greyhounds. He’s famous for being a hard-ass. The running joke is that his secret formula is to treat people like animals.

But for the past ten years, Sutton has been a pariah in the sport, because of a crime he was arrested for in 1997, when he was coaching the Australian national triathlon team in preparation for tri’s debut at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. In 1999 he confessed to having had sexual relations several times with a female swimmer he coached in 1987 when he was 27 and she was reportedly 14. Investigations after his arrest indicated that this episode was an isolated case; Sutton, it appeared, was not a serial pedophile. He received a two-year suspended jail sentence for sexually assaulting a minor and a three-year sanction by the International Triathlon Union and Triathlon Australia, the governing bodies associated with the Olympics.

During the sanction, he was suspended as a coach and banned from national sports facilities in Australia. He was also barred from attending national and international events, and when he showed up at a race in Japan a few months later, he was escorted out. An official told reporters, “It was like having a black cloud over the race.”

Sutton never stopped coaching, though, and several of his athletes followed him, including Harrop, who would go on to win the silver medal at the 2004 Olympics. Freed from the restrictions of overseeing a national squad, Sutton assembled an international group of triathlon specialists. He set up shop in other countries, such as Switzerland and Brazil.

For years, he earned his living by charging athletes a monthly fee and taking a cut of their winnings. (Which aren’t as large as you’d think. Even a star like Wellington is lucky to pull in around $150,000 a year in prize money.) Last year, a new sponsor took over Sutton’s team an Asian bike-shop chain called the Bike Boutique so he no longer draws money directly from the athletes, a shift that has allowed him to be even choosier about whom he invites onto his team. In the past, one knock against him was that he had never produced a Hawaii Ironman champion. Now, few will be surprised if his athletes start dominating the event.

Although Sutton’s home base is Leysin, Switzerland, where he holds a summer training camp, he prefers Third World countries for his fabled “heat” camps: two months of hard training in a sweltering, humid climate to prepare for the start of the race season, and two more rounds of the same thing before and after Hawaii. In February of this year, he took his team to the U.S. Navy’s defunct base at Subic Bay, in the Philippines, for the first of them.

Sutton has rarely let outsiders in while he works, but when Wellington scored her historic win, I set out to meet him. After five months of back-and-forth by e-mail, he agreed to let me visit him in the Philippines. I was told that everything, including his past, would be up for discussion. I had my doubts, but when we sat down around a coffee table during my first night in camp, I was surprised that he started unloading right away.

Sort of. Sutton, who has a rugged, green-eyed face that’s seen some hard road, didn’t say much that was directly related to the assault charge. Instead he talked about a harsh childhood under the pressure exerted by a father who was a demanding swim coach. “I come from an extremely violent home,” he said. “I was the most passive.” His swimming was poor, but his father led him into coaching at the age of 10. He was almost 15 when he was kicked out of school for coaching in a professional program. He left home and found work at dog- and horse-racing stables in New South Wales. He also said he has suffered from manic depression, and that it kicked in before his arrest, at a time when he was gaining a global reputation as a tri coach.

“I had a business partner who’d killed himself,” he said. “So I was already in a bad way.”

It all sounded a little staged, as if Sutton was trying to offset whatever I might think about his sex crime. But I don’t think the self-loathing was an act. At the hotel one morning during my stay, Sutton came by and sat down while I ate breakfast. He talked for an hour about his training philosophy, and then he visibly sagged as his mind turned to the bad old days.

“People think because you’ve had some success you can forget about certain things in your past, that you can get over it,” he said. “It’s not something that comes and goes. I’ve always hated myself viciously. Now I just hate myself for different reasons.”

SUTTON KNOWS HE has enemies. Athletes invited to join his squad, team TBB, are warned that he’s “damaged goods.”

“I get the rejects, the ones who are desperate,” he says melodramatically. “Others won’t come near me because I’m tainted.”

Obviously, athletes like Wellington have accepted who he is. “All I could do is go by what I saw and the relationship I established with him in a short amount of time,” she told me in the Philippines. “I saw nothing that gave me any concern, and still haven’t.” What they get in return is a level of expertise that will take some of them to the top. For this reason, Sutton has no shortage of applicants, and he tends to turn people down at least twice before agreeing to coach them. He almost always says no to Americans, whom he considers “soft.”

The morning after my first talk with Sutton, he gives me a ride in his minivan to a 7 a.m. swim session at a community swimming pool. Twelve sleepy-looking triathletes are sitting under a palm tree, eagerly waiting for the gate to be opened among them Wellington and Reto Hug, a two-time Olympian from Switzerland. Some of the athletes are away from the camp right now, but the full squad numbers only 18. Sutton prefers not to work with too many people at once, a rarity in the age of Web coaching. “I know I could have 100 people here and make more money,” he says. “But that’s not what I’m about. Coaching is sacred to me.”

During the 90-minute session, they will swim three miles’ worth of intervals, the first of the day’s three workouts. In the hours ahead, I’ll see a few glimpses of Sutton’s hard-man side. One of the triathletes has a water bottle on deck and starts sipping from it between swimming sets. Sutton sees it and hurls it over a fence. “I haven’t yet seen an aid station at an Ironman swim,” he shouts. “If you win a world championship, then you can bring a drink.”

The Bobby Knight moments are few, however, and what stands out more is Sutton’s ability to see into the depths of an individual. He examines each athlete and issues unique instructions one-on-one, as if he were coming up with plans on the spot. Greg Bennett, whom Sutton turned from an average pro to a star in the late nineties, told me about the Sutton eye.

“He has learned how to read animals that are fatigued,” he said, “so when he’s taking on people, isn’t that just another animal?” Bennett added that this skill helps Sutton push his athletes to the brink but not over it. “There were weeks and months where I pushed myself harder and longer than I ever could have imagined. You go into a workout thinking, There is no way I can do what he’s after, and yet day in and day out your body responds.”

In the pool that morning, Wellington does her swim with Bella Comerford, a 31-year-old Scot. Wellington and Comerford demonstrate the contrasting types that Sutton looks for in athletes: They have different levels of natural ability, but they both have a killer work ethic. Wellington, who came to Sutton after competing at the amateur level for three years, was the type of raw talent that other coaches might have overlooked. But she has incredible genetic gifts Sutton calls her a “thoroughbred” so she needs only a few months of training to achieve good form.

Comerford, in contrast, wins by virtue of hard work. “A plow horse,” Sutton calls her. Even if she never wins at Hawaii, in the series races that are triathlon’s bread-and-butter, she’s a star. In the first half of 2008, she won Ironman South Africa and Ironman Lanzarote, the latter contested on what’s considered the toughest course in the sport.

“We call her the little Nazi,” Sutton says. “Bella is my champion soldier.”

SUBIC BAY LIES ABOUT a four-hour drive northwest of Manila. Since the Navy left in 1992, the local government has attempted to transform the area into a tourism destination. Today, for the most part, it’s a partially developed ghost town, with various casinos and hotels, including the Grand Seasons, where Sutton and many of the athletes are staying.

I watch the team train for three days. Rumor has it that Sutton runs a torture academy there are tales of athletes sprinting in wetsuits and of nine-hour bike rides. Those things can happen, but what I see is fairly simple. The team swims an hour and a half per day, bikes two hours or so, and runs more than an hour. A five-hour training day, with the occasional day off, is standard. The really hard part is doing this week after week. Belinda Granger, a 37-year-old tri veteran from Australia who’s been working with Sutton for the past two years, tells me that when a new athlete joins the program, the raw volume can be a shock. “They go backwards before they go forwards,” she says.

��

“If it’s not long, it’s got to be hard,” Sutton quips about the workouts, underlining his belief in interval training repeats of fast-paced efforts interspersed with short recoveries. Then there are Sutton’s infamous “black” days Black Wednesday, for example when he issues a virtually endless succession of intervals. During one session, the team swims six miles’ worth of them: 100 meters, 100 times. I was told of another challenge in which the team ran 35 miles in 100-degree heat.

“What fascinates me about Brett is this emphasis on the mental side,” Wellington says. The value of a Black Wednesday, she says, is psychological toughening. For this to work, the athlete has to trust Sutton completely. He demands and gets total submission. If he doesn’t, the athlete can expect to be booted.

“There is a procedure to becoming a world champion,” Sutton says. “It’s not a natural one. It’s not normal. If you want to be a civilian, be a civilian. My athletes are soldiers. This is the jungle. The lion gets up every day. If he doesn’t catch the gazelle, he doesn’t eat. If the gazelle doesn’t outrun the lion, he’s dead.”

Another Sutton admirer is Alec Rukosuev, a former pro triathlete who coaches at the National Training Center in Clermont, Florida, a site for athletes from around the world. For him, it’s simple: Sutton’s methods work. “Guys like Brett are the ones doing it right,” he says. “He has a strong personality. All the great coaches do. They are like Napoleon. People will do anything he says.”

IF SUTTON WEREN’T a famous coach, my guess is that his long-ago crime might be forgotten by now. But it will always be there, and there are people who think he still doesn’t belong in the sport. Richie Cunningham, a professional triathlete from Australia, says, “I would never be coached by the guy. I guess for some it’s OK to sell your soul, as long as you end up winning.”After Wellington’s win, Nikola Tosic, a Serbia-based triathlete and blogger, posted a picture of her with a speech balloon pasted in, which has her saying, “I want to thank my coach, Brett Sutton, a convicted child molester.” Tosic didn’t know about Sutton until Ironman coverage prompted him to search the Web. On his blog he wrote, “Brett Sutton is a convicted sexual abuser of children. For some super crazy lucky reason he is not serving a life sentence or something like that.”

No one has disputed the basic facts surrounding Sutton’s past: He had a sexual relationship with a girl under 16. The girl (whose name has never been made public) grew up and changed sports. When the scandal finally broke, 11 years later, she was married to a triathlon coach named Spot Anderson. They have since divorced.

Recently, I spoke with Anderson about how and why the episode eventually came to light. “Sutton was asking me if I wanted to be an assistant coach for the national team,” he recalled. Anderson wasn’t interested in coaching elites, but the offer prompted a discussion about Sutton with his wife. “Then she told me the story,” Anderson said.

Anderson called Rob Pickard, then a performance manager for the Australian national triathlon team. “I knew Spot pretty well and listened,” Pickard says. “I said, Well, Spot, if you’re that concerned, why are you telling me? If it’s true, you should tell the police.’ “

In 1997, three years before the start of the 2000 Games in Sydney, Sutton was running a swim clinic at the Australian Institute of Sport when police showed up and arrested him. Against the backdrop of triathlon’s Olympic debut, the emotionally gripping story swept the Australian media, generating headlines like DREAM COACH ADMITS SEX WITH GIRL.

Sutton was charged with ten counts of what, in Australia, is called “indecent dealings” with a minor. Anderson says he pressed for a rape charge, which carries a stiffer penalty, but the police dismissed this after their investigation. In the end, Sutton pleaded guilty to six counts of indecent dealings. But his position has been that, even though the sex shouldn’t have happened, it was consensual. When he talked about the case later, he went on the offensive.

“Everyone yelled it was rape, but it wasn’t rape at all,” he told one Australian reporter. “I was never going to, under any circumstances, plead guilty to rape or anything like that. I wanted the charges changed to something more appropriate, and they did that.”

At one point during my e-mail correspondence with Sutton, I asked him to verify certain details about the three-year sanctions he was supposed to serve. He took that as a cue to rail against that penalty one more time. “The whole situation was a farce,” he replied. “They could cancel my registration, with their organizations, legally. They could do absolutely nothing more. The barring and stuff was all fantasy on their behalf.”

The takeaway? Sutton is sorry in some ways, defiant in others. If he wanted to, he could show up at Kona this month, clipboard in hand, but I don’t think he will. Instead he’ll stay in the limbo zone, sending athletes out there to make his statements for him.

THE FINAL AFTERNOON of my stay in the Philippines, I ride in Sutton’s van as he follows Wellington on a hard bike ride. He’s sent the team off in front of her, explaining to me that her bike strength was demoralizing not only most of the women but some of the men. “Look at that,” he says, pointing to the speedometer as we buzz along a flat road. It reads a bit over 30 miles per hour. “This is what I was seeing last year. And people thought I was crazy to send her to Hawaii.”Wellington is looking fitter than she did last October, stronger and several pounds lighter. Wellington has said it’s important to her to show the world she’s for real. Having crushed the doubters, the question now is whether she will break to pieces, get sick of it all, or leave Sutton. Another rap is that he burns people out. One of those who stuck with him the longest, Loretta Harrop, struggled with injuries in the last part of her career.

“We’ve gone up against Sutton for 20 years now,” says Pete Coulson, an Aussie who has coached his wife, Michellie Jones, from the early 1990s to the present. “I think Michellie came in second to four of his world champions. If you look at results only, he’s the best coach there is, no doubt about it.”

Coulson’s criticism of his rival centers on the cumulative mental and physical punishment he doles out. “You look at his athletes, they’re phenomenal for about two years and then they’re gone. Michellie wouldn’t last in his program. Do you want to be great for two years, or do you want a career? Time will tell with Wellington. Looking at her right now, she may be the best Ironman triathlete ever produced.”

Rukosuev who grew up training on a swim team in Siberia doesn’t see the problem. “It was when I was closest to injury that I had my best races,” he says. “Would you rather have the two years of success or five years of mediocrity? Yes, Sutton buries you. Or you could be mediocre for five years. Who cares?”