It’s pretty clear, at this point, that plyometric training can make you a more efficient runner. There’s still plenty of debate about how it works. Does it streamline the signals traveling from brain to muscle? Does it make your tendons stiffer, enabling them to store and release more energy as they’re stretched with each stride? Does it alter your running style so that you take quicker and lighter steps? No one is sure, but there’s little debate that it does something.

As a result, studies like , published last month by a group led by Aurélien Patoz of the University of Lausanne, don’t garner much attention. They found a 3.9 percent improvement in running economy after eight weeks of either plyometric or dynamic strength training, roughly comparable to what Nike’s original Vaporfly 4% shoe produced. (They also found no evidence that either form of training altered running stride in any significant way, for what it’s worth.)

Why no excitement about a free four-percent boost? As someone who has experimented on and off with various forms of plyometric training over several decades, let me venture a hypothesis: it’s perceived as too complicated, and possibly risky, for most of us. Plyometrics involve explosive movements in which you try to maximize the force produced in the shortest possible time. You often see people leaping off steps, bounding over hurdles, and performing various other feats of impressive coordination.

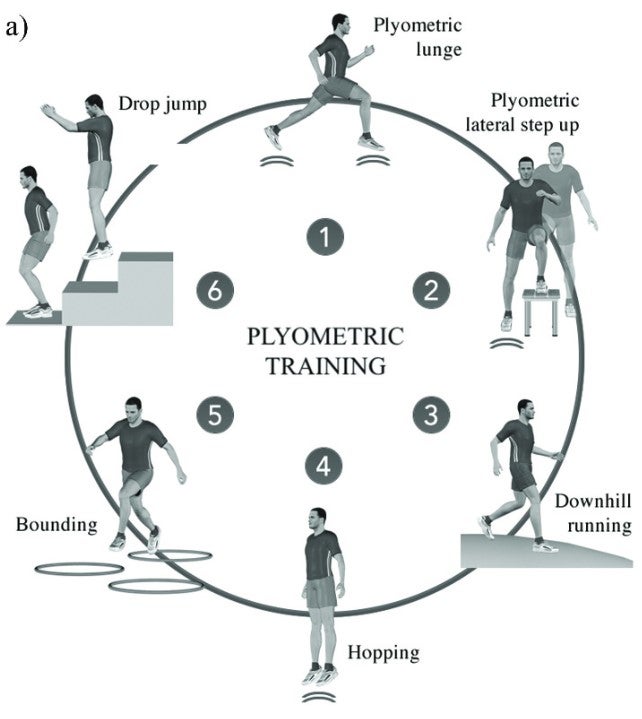

The subjects in Patoz’s study were amateurs with no prior experience with any form of structured strength training. As a result, the exercises they did weren’t especially daunting by plyometric standards. But they weren’t simple, either. Here’s an overview of the program:

Even if you think your hamstrings can handle drop jumps, plyometric lunges, bounding and so on without snapping, you still need various bits of equipment and a bunch of time. Does it need to be that complicated?

That’s the question tackled by , this one led by Tobias Engeroff of Goethe University Frankfurt and published in Scientific Reports. They stripped plyometric training down to its bare bones, tested it on a group of amateur runners—and still found a significant improvement in running economy after just six weeks. The exact size of the improvement depends on how you measure it and at what speed, but was between 2 and 4 percent.

Engeroff’s plyometric program involved nothing but hopping on the spot. Specifically, “participants were instructed to start with both feet no wider than hip width apart and to hop as high as possible with both legs, keeping the knees extended and aiming to minimize ground contact time.” They started by hopping for 10 seconds, resting for 50 seconds, and repeating five times for a total of five minutes. They did this five-minute program daily, decreasing the rest and increasing the number of sets each week: the second week was 6 sets of 10 seconds of hopping with 40 seconds of rest; the sixth and final week was 15 sets of 10 seconds hopping with 10 seconds of rest, still totaling five minutes.

This program was based on the idea that it’s tendon stiffness that boosts running economy. In particular, the stretch and recoil of the Achilles tendon provides between half and three-quarters of the positive work required for running, by some estimates. Engeroff’s short daily program draws on recent research by Keith Baar and others suggesting that connective tissue such as tendons responds best to brief, frequent stimulus rather than longer and harder workouts. Notably, this approach didn’t injure any of the runners.

The point here isn’t necessarily that daily hops are the new magic exercise that everyone should do. Indeed, it’s worth emphasizing that Patoz’s study found essentially the same improvements with both plyometrics and dynamic strength training. That’s a familiar result in studies that have tried to determine the best economy-boosting regimen: all sorts of different approaches seem to produce similar results. Patoz’s dynamic strength program involves a bunch of bodyweight exercises that focus on concentric contractions: lunges, step-ups, squats, stair jumps. Those are all components of my current strength routine, and I like the idea that, in addition to stiffening my tendons, I might also be strengthening my muscles.

It’s worth acknowledging that the subjects in both these studies were recreational runners with little prior experience of either plyometric or strength training. The minimalist program that works for them might not do much for a serious competitive runner with years of resistance training experience. Those are the people who might need to do the elaborate one-legged triple-axel hurdle hops that you see in online training montages. For the rest of us, though, the message seems to be: do something. It’s as effective as supershoes, and way cheaper.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book.