The Nike Vaporfly 4% wasn’t shy about how much of a boost it claimed to give runners: the promise was right there in the name. When the shoe was released back in 2017, researchers at the University of Colorado published data showing that it improved athletes’ running economy (i.e., efficiency) by an average of 4 percent over the best marathon shoes at the time. Chaos—and a whole bunch of world records—ensued.

The key ingredients in the Vaporfly were a stiff, curved carbon-fiber plate embedded in a thick layer of soft-but-resilient midsole foam. Neither of these elements was magical on their own, but they somehow combined to make runners substantially more efficient, for reasons that scientists don’t fully understand and are still arguing about. Since then, virtually every major shoe brand has come up with multiple iterations of the so-called “supershoe,” tweaking these basic ingredients in minor and sometimes major ways.

But a key question has remained mostly unanswered: are the newest shoes significantly better than the original Vaporfly? A few researchers have run head-to-head tests of models from different brands, with generally muddled results. Some newer shoes might be a percent or two better, but there’s so much individual variation that it’s hard to be sure. Since Nike’s bold move in 2017, the shoe brands themselves have mostly steered clear of making explicit claims about how good their shoes are.

That’s about to change. Puma, a veteran shoe brand that relaunched its serious running line in 2018, has a new shoe dropping in time for this month’s Boston and London marathons. They think it’s dramatically better than anything else on the market—about 3.5 percent better, in fact. They’re so convinced that they arranged to have the shoe tested by Wouter Hoogkamer, the head of the Integrative Locomotion Laboratory at UMass Amherst and, as it happens, the man who led the external testing of Nike’s Vaporfly back in 2017. Hoogkamer released his data earlier this week, and it’s impressive.

What the New Data Shows

Hoogkamer’s study is posted as a preprint on bioRxiv, a site where scientists share their results while awaiting peer review. He and his colleagues brought in 15 volunteers, all of whom had run under 21 minutes for 5K (for women) or 19 minutes (for men). To test their running economy, he had them run on a treadmill for five minutes at a time while measuring their oxygen consumption. The more oxygen you consume at a given pace, the more energy you’re burning and therefore the less efficient your movements. A good shoe should maximize your efficiency—and therefore minimize your oxygen needs—at a given pace.

Each runner had their economy tested eight times: twice each in four different shoes. The comparison shoes were the Nike Alphafly 3 (which Kelvin Kiptum used to set the men’s marathon world record and Ruth Chepngetich used to set the women’s record); the Adidas Adios Pro Evo 1 (which Tigst Assefa used to set the previous women’s marathon world record in 2023); and Puma’s top-of-the-line . The newest Puma supershoe is an update of this latter model. It’s been dubbed the Fast-R Nitro Elite 3 (original, I know).

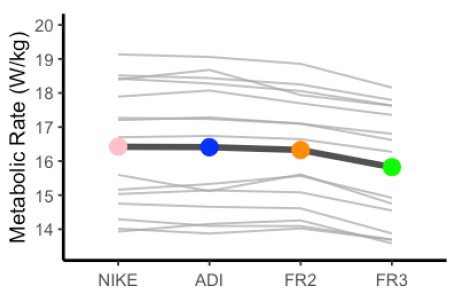

Without further ado, here’s the running economy data for the four shoes. Metabolic rate, in watts per kilogram, tells us how much energy the runners were burning at a prescribed pace that was assigned based on their 5K PR, ranging between 6:00 and 7:30 per mile. The thick line shows the average results, the thin lines show the individual ones.

It’s clear that the Fast-R3 resulted in the lowest metabolic rate across the board—which means it’s the most efficient shoe. The runners burned 3.6 percent less energy wearing the Fast-R3 than they did in the Nike shoe, and 3.5 percent less than in the Adidas. (Some free marketing advice: they should have called the new shoe the Fast-R3.5.) It also burned 3.2 percent less energy than the Fast-R2—making the new model pretty significant update from its own previous edition. What’s even more remarkable, given the wide range of individual results seen in previous supershoe studies, is that every single one of the 15 runners was most efficient in the Fast-R3.

Puma has also run its own internal testing on more than 50 runners, according to Laura Healey, who heads the brand’s footwear innovation team. In their data, the shoe is 3.3 to 3.5 percent better than its rivals. Running economy doesn’t translate directly to race time, but a boost of 3.2 percent (the margin between the Fast-R2 and the Fast-R3) is expected to reduce race times by about 2.0 percent for a 2:00 marathoner, 2.6 percent for a 3:00 marathoner, and 3.3 percent for a 4:00 marathoner.

What’s the Magic Ingredient?

With the Vaporfly, it was easy to understand—at least superficially—why the shoe was different from its peers at the time: it had that thick foam and carbon plate. It’s harder to get a handle on what makes the Fast-R3 special, because the basic architecture is the same. The differences between the Fast-R2 and Fast-R3 are subtle, but the running economy data shows that they’re significant.

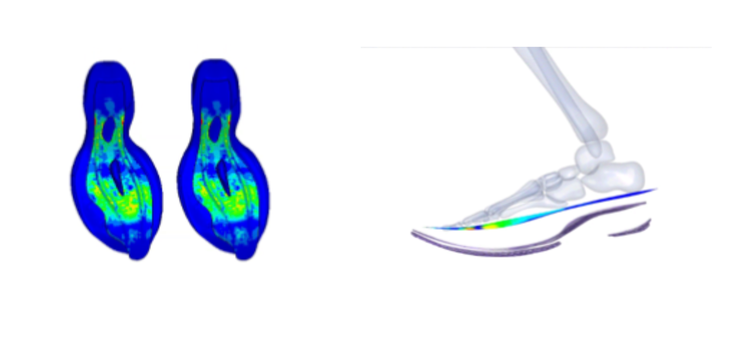

Puma’s team started with the Fast-R2 and created a virtual model of the shoe using biomechanical data collected from ten runners wearing pressure-sensing insoles while running on a force-sensing treadmill. The model showed exactly what was happening inside the shoe at each instant during a running stride: where the forces and strains were highest and lowest, how the shoe was bending and compressing, and so on.

Then they went through a process of iterative computational design and optimization. For example, if the virtual model showed that a particular area in the midsole wasn’t experiencing much strain, they would remove some of the foam in that location. Or if it showed that a region of the carbon plate was excessively strained, they would reinforce it with a rib of extra carbon. All this was done digitally within the virtual model, so they could see if the changes made the situation better or worse without going through the hassle and expense of building a new prototype.

By the time they finished this virtual optimization process, they’d snipped away enough superfluous foam and carbon to reduce the weight of the shoe by more than 30 percent, from 249 grams to 167 grams. There’s a rule of thumb that adding 100 grams to a shoe worsens running economy by about 1 percent, so this 82-gram reduction accounts for about 0.8 percent of the Fast-R3’s advantage. As for the rest, there’s no single obvious change that explains it. Instead, the iterative process of making sure every bit of foam and carbon fiber is contributing seems to have created a more efficient shoe.

There are some other subtle differences. The Fast-R3 is a little less stiff than its competitors when you try to bend it along its length, and a little less stiff when you compress the midsole—but it returns slightly more energy when it springs back. The foam in traditional running shoes returns about 65 to 75 percent of the energy you spend compressing it. Superfoams such as PEBA in the Vaporfly and other supershoes return about 85 percent. Puma’s Nitro Elite foam, an “aliphatic thermoplastic polyurethane” (A-TPU), returns over 90 percent. In Hoogkamer’s testing, compressing the whole shoe (not just the midsole foam) returned 89.9 percent of the energy, compared to 85.0 percent in the Nike shoe and 85.7 percent in the Adidas.

What Happens Next?

There are a lot of reasons to be skeptical of any shoe company’s claims about its newest model. Hoogkamer doesn’t work for Puma, but his study was funded by them, just as his Vaporfly study was funded by Nike. Both studies were small. Subsequent events showed that the Vaporfly’s 4-percent boost was real and spectacular. Over the coming weeks, we’ll get a sense of whether the Fast-R3’s 3.5-percent boost also passes the real-world test.

One problem is that Puma’s roster of elite road runners isn’t as impressive as Nike’s or Adidas’s. At first glance, they don’t have anyone who’s likely to set an attention-grabbing world record. Still, we’ll start seeing the new shoe in action at the Boston Marathon on April 21 and the London Marathon on April 27.

One of the athletes who will be wearing it in Boston is Rory Linkletter, a 2:08 marathoner from Canada. He’s been training in the shoe, so I asked whether he could tell that it was different. He said the first thing you notice is how light it is, and the second is the springiness: “It’s softer than previous supershoes, and that softness is met with some pretty remarkable bounce.” He doesn’t have enough experience with it to know whether it’s faster, but he’d just done an 8-mile tempo run along Lake Mary Road in Flagstaff that was a minute faster than he’d ever previously done.

If Linkletter sets a big PR in Boston, it will be impossible to know how much credit, if any, should go to the shoe. But over the months to come, we might start seeing some patterns—and seeing whether other shoe companies adopt similar computational approaches, if they haven’t already. The “many small tweaks” approach of the Fast-R3 means there’s no single gimmick to copy. It also means that further refinements might be possible. Five years ago, I wondered whether supershoes were like klapskates in speedskating (one big innovation followed by a plateau) or tech suits in swimming (a series of innovations that kept making swimmers faster and faster). It’s starting to look like option B.

—

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my new book .