THERE ARE RUNNERS on first and second and two outs in the top of the first inning of the first game of organized baseball I’ve played in seven years, and on the pitcher’s mound, a large inverted triangle of a man with thin eyes set deep in a bone-ridged face toes the rubber. His name is Mario. Behind him, the green hump of Marin County’s Mount Tamalpais rises over a high concrete wall and one palm tree wavers. The wooden bat is a welcome, familiar weight in my sweating fingers, and the soles of my cleats are heavy, weighed down with clumps of infield mud. Gulls circle, and I can smell the sea. They made baseball for afternoons like this.��

Gaming the System

Several prisons worldwide are known to organize sporting events for their prisoners.Mario

Mario is a pitcher for the San Quentin Giants baseball team.

Mario is a pitcher for the San Quentin Giants baseball team.Johnny

Johnny is the catcher for the San Quentin Giants baseball team.

Johnny is the catcher for the San Quentin Giants baseball team.��

The crowd, a group of about 150 inmates clad entirely in blue and positioned behind home plate, murmurs. Mario wears a permanent grin. Good pitchers don’t grin. Good pitchers, the tired adage goes, are killers.��Mario’s fastball can’t be faster than 75 miles per hour; his curve is a long, slow loop. He’s not a killer. At least, I don’t think so.��

“Thanks for coming,” says a voice from behind me as I step into the batter’s box. “It’s a real honor. My name’s Johnny.”

I look back. The catcher, a taut, wiry man, stares up with wide eyes. The tattoos on his neck appear to have tattoos on them.��Johnny—now, Johnny could be a killer.

“Thank you,” I say.

In baseball, as in any sport, you play best when you empty your head and keep it simple. Your thoughts should not extend beyond preparation for reflex. Then you step up and get to it.

But just now, as Mario checks the runners, lifts his leg, and delivers, the noise in my head is rattling.��

Mario, Johnny, I think. What did you do?

I'M HERE, LIKE MANY before me, as a member of the visiting team. , a 159-year-old, mostly medium-security correctional facility home to 5,000-odd inmates, including the murderer , is the only prison in America that invites civilians inside its walls to compete with well-behaving felons who wear spikes and swing bats. I first heard about San Quentin’s teams— and their brother team, the A’s—in the summer of 2009. I’d played baseball in college, and a former teammate, Alex, had e-mailed me about his San Quentin experience. “The tans of the prisoners were EPIC,” he wrote, “and that stereotype you see in movies about a guy dressed like a girl who gets handed around to other prisoners is absolutely true!”

I wanted to see for myself, but getting in is complicated. In 2007, a filmmaker made a documentary about the Giants (title: ), and every spring a few Bay Area newspapers preview the season. But the prison’s wardens tightly control access and spin on these stories, and they often bar journalists who want to watch the games.

Last summer, Alex introduced me over e-mail to the Giants’ liaison to the outside world, a San Francisco real estate attorney named Elliot Smith. A diminutive 69-year-old man with a Tom Selleck mustache, Smith spends the majority of his free time as one of the Giants’ four coaches, a role that requires arranging the team’s schedule, recruiting opponents, and running a series of highly competitive tryouts each spring. (On a team dominated by lifers, attrition is rare.)

Smith is a self-described product of the sixties with a long-held interest in social justice. “You’re helping humanize people in a dehumanizing system,” he says. “Baseball is my vehicle for��doing that. I spend a lot of time talking to guys while the game’s going on. Guys need someone to talk to.”

In June, Smith told me he was short a few opponents for an upcoming game and��needed players. That’s how I’ve come to be facing Mario. I’m playing center field alongside a motley collection of players from Smith’s Bay Area men’s league. There are seven of us,��accountants and law-school students and beer-league all-stars, all clad in red.��

Smith tells me that playing here is safe, because a spot on the Giants is perhaps the highest privilege in the California penal system, one that no idiot wants to sacrifice by picking a fight with a visitor. “You’re often dealing with people who have killed people for one reason or another,” he says. “But you have to compartmentalize that: they did what they did, but they’re still human beings. They’re not animals. The only trouble we ever had was two players on the same team almost getting in a fistfight. A guard raised his rifle, then realized they were visitors.”

During warm-ups today, a siren went off and all the inmates, including the Giants, sat down on cue while the guards in the rifle towers did a sweep of the yard. This was zero-tolerance time. Still, there are no officers on the field, just us and the Giants. And, it should be noted, before we walked into the prison, via a series of wrought-iron gates out of Game of Thrones, Smith told me, “As a formality, I have to warn you that they don’t negotiate for hostages here.” I laughed, he didn’t.

The ball emerges from Mario’s hand like a fresh egg, and reflexes take over. I reach out and get all of it, which is to say I feel nothing. When you hit a baseball perfectly, it’s all light and air, as if performing this most difficult task were the easiest trick in the world. The ball takes off toward right center and I sprint toward first, then nearly face-plant after slipping on a slick metal plate that sits, inexplicably, in the middle of the baseline. When I right myself, I see the ball land in the center fielder’s glove, just in front of a group of Hispanic guys playing chess. Warning-track power is a cruel lord.

BASEBALL IN SAN QUENTIN dates to the 1920s, but it became well-known three decades later, when pro scouts brought prospects into the prison to bat against a former major league pitcher named Blackie Schwamb, who had been incarcerated in 1948 for murdering a Long Beach doctor. Starting in the 1990s, San Quentin began hosting men’s-league teams from the Bay Area. The home team was named the Pirates. A skull and crossbones flew from a flagpole in the prison yard. In 2000, the team changed its name when San Francisco’s big-league team donated its used game jerseys and grass for a new field.

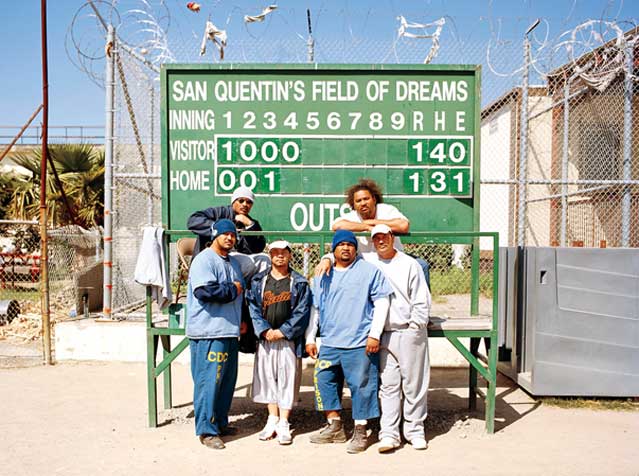

San Quentin’s field is the misshapen green heart of the prison yard. It’s surrounded in right and center field by a high concrete wall topped with razor wire and guard turrets. The infield contains no grass, and on the day I visited right field was occupied primarily by a shallow pool of water. A steady stream of inmates with impressive body art walk around an exercise path that doubles as the field’s warning track. Beyond this, past right-center field, sit a row of chess tables. One of San Quentin’s house rules holds that a batted ball that hits an inmate at the tables is a ground-rule double. The players on the field are the only racially integrated group of people in San Quentin. Out in the chess tables, people gather according to color: the black guys here, the Mexicans there, the white dudes underneath the manually operated scoreboard, which reads SAN QUENTIN’S FIELD OF DREAMS.

Home plate faces away from the��prison’s hospital, the adjustment ward, death row, and the cell blocks. The effect of this is somewhat illusory. All the batter sees is the field and the chess tables, Mount Tam, the lonely palm tree, the razor-crowned wall, and the scoreboard. You can’t see the bay or the million-dollar homes or the sailboats, but you feel their presence. It’s either a brilliantly appropriate name for a field or a merciless one.

Because we’re short on players, we’re forced to put Smith at third base and pick up two new members of the Giants:��Louie, an infielder who recently transferred to San Quentin, and Chuck, an outfielder with mirrored sunglasses, braids protruding from a do-rag, and a fixed smile.

Chuck tells me he’s a 45-year-old former firefighter. He’s in right field and I’m in center; we hit it off, me asking for scouting reports on the Giants’ hitters and him delivering them with brutal candor. The center fielder is a dead pull hitter, the shortstop and third baseman are home run threats, and the leadoff guy can’t hit.

Chuck is a very good fielder who has a friendly demeanor, the sturdy build of a running back, and a cavernous hole in his swing. After he strikes out looking in his second at-bat, we talk shop on the bench.

“That third strike looked low,” I say.

“Yeah, it was low!” he says. “I just have to practice. Spend some time in the cage.”

“You have a batting cage?”

“N��!” he says, shades glinting. “That’s the problem!”

THE GAME MOVES quickly, with our pitcher, a Stanford undergrad, mowing the Giants down. Their hitting has suffered in the past year. In fact, according to Smith, everything about the program has��suffered in the past year. “The first thing was the rain,” he says. “That set back the season.” Tryouts usually happen in February, then the team practices in March and starts its 40-game schedule in April. This year, tryouts didn’t happen until March. “Then it stopped raining,” Smith says, “and we had a chicken pox epidemic, and they shut down the prison for a couple weeks. Then we had problems with players getting hurt or having attitude issues or getting transferred. We had our best��pitcher get the shit beat out of him by a bunch of guards. He never came back. He was hospitalized for quite a while, and I don’t know what happened to him. So we were really down. Then a couple guys walked off the team.”

According to Smith, it’s an open question each year whether San Quentin’s wardens will renew the program, even though the team doesn’t cost any money. The coaches are volunteers, and the equipment is donated. Smith has a ballplayer’s disdain for the present. “In the old days, when the yard was more open, you’d get hundreds and hundreds of people watching a game on a weekend,” he says. “The field was literally ringed with inmates. A lot of them would be yelling. Sometimes it was funny, and sometimes they’d be shaking the fence. That was tense. That was the real San Quentin��experience. It’s not like that anymore.”

It sure isn’t. Early in the game, someone in the chess tables screams, “Hey Louie, tuck in your shirt so I can see your ass!” But��after that, the crowd has a slack energy. Hard to blame them: it isn’t so much a game as a series of weakly hit fly balls and strikeouts.

Then, in the bottom of the fifth, the score tied at zero, a sharp ground ball is hit down the third-base line. Smith stops it with a quick stab, the jagged movement of a man retaining the last drops of his athleticism, and heaves the ball toward first. The throw dangles in the air for a long time before ending its downward arc in our first baseman’s outstretched glove. When Terry, the rangy inmate umpiring at first base, gives an emphatic punch-out signal, the yard erupts, giving Smith his due: “E�����������������������������������հ�!”

In the top of the sixth, we finally break through, thanks to a pop-up that falls between three standing Giants, a walk, and a San Quentin ground-rule double that ricochets off a spectating inmate. With the score 1–0, Mario intentionally walks the hitter ahead of me, loading the bases. You may not be familiar with all of baseball’s nuance, but surely you know this: intentionally walking a batter to load the bases so you can get to the next guy is the greatest insult in the game. I work a walk to force in a run, my first and last time on base.

WE'RE WINNING 3–0 when Smith calls the game for darkness after the sixth inning. We shake hands with the Giants, who are a picture of grace. Mario’s face is a big, childish smile hiding deep-set brown eyes.��

“Where are you from?” he asks.

“Santa Fe,” I say.��

He tells me he’s spent some time in Albuquerque and liked it, and I concur that it’s a good town, and we pause awkwardly, as though this agreement has created some temporary bond. He walks away, and I follow my teammates out. We’ll soon pass the adjustment ward and death row, and a small, doughy guard with the complexion of paper and an insipid smile will tell us that the guys we just played would “rape, kill, and murder anything in sight” should they be let free. We will walk to our cars and drive toward San Francisco, over the great shining bridge, our windows down and our radios up. First, though, we pass Johnny, the��catcher, and Terry, the first-base umpire, who are standing behind home plate. I stop to linger.

“It’s a real honor for you to come here and play us,” Johnny tells me again. He walks with a limp; it appears that the game has beaten him. I shake his hand, then Terry’s.

“You’ve got to come play again,” Terry says.��

I tell him that I would love to, but that I live in New Mexico.

“That’s OK. Come back out later this summer,” says Terry.

I tell him that there’s travel coming up. “That’s OK, come next summer.”

He smiles, and I pause. It strikes me that the earnestness is not a put-on. Terry and Johnny are just truly bored, and, at least to me, they’re truly kind. I’ve never met a group of people for whom sport is more essential. Then I ask a painfully obvious question.

“You—you’ll be here next summer?”

“Oh yeah,” Terry says. “I’ll be here for the next 17 years.”