At last monthтАЩs World Cup cross-country-skiing event in the northern Finnish resort town of Ruka, some of the top competitors, including Finnish Olympic champion Iivo Niskanen, chose to withdraw at the last minute. тАЬItтАЩs not too long to the Olympics,тАЭ Niskanen . тАЬMinus 23 [degrees Celsius, or -9.4 degrees Fahrenheit] is too much for me. A simple choice.тАЭ

That surprised me, to be honest. Several decades of running through Canadian wintersтАФoccasionally, though not frequently, in temperatures colder than thatтАФhas left me with the general feeling that itтАЩs almost never too cold to exercise outside as long as youтАЩre appropriately dressed. I even wrote an article about how to survive those frigid runs a few years ago. But of research on sport in cold environments, published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health by a team of researchers from Italy, Austria, and Canada, takes a somewhat more cautious view of things.

The review is online, but here are some of the highlights:

Cold Hurts Performance

The research here isnтАЩt quite as much of a slam dunk as you might expect. NobodyтАЩs setting world records in Arctic conditions, but the reasons for the performance drop arenтАЩt as obvious as they are in hot weather. For example, one study from the 1980s had cyclists ride to exhaustion at either 68 F or -4 F. There were no differences in their oxygen consumption or heart rate at a given pace, but the cyclists nonetheless gave up after 67 minutes in the cold condition compared to 112 minutes in the warm condition.

There is evidence that warm muscles function better: by , an increase of one degree Celsius (0.6 degrees Fahrenheit) in muscle temperature boosts strength and power by two to five percent. This likely affects both endurance sports and strength/power sports, and impaired muscle coordination in the cold may also raise injury risk in sports like downhill skiing. But these subtle physiological effects are probably only part of the story: being really cold is also psychologically distracting and distressing, and that undoubtedly plays a role too.

You (Sort of) Get Used to It

The big news for Canadian soccer fans last month was their national teamтАЩs in a World Cup qualifierтАФthe first time that has happened since 1976. The game took place in Edmonton, where the temperature at kickoff was 16 degrees Fahrenheit. Did the Canadians have a physiological advantage? Meh. If there was one, it was marginal at best. As a put it a few years ago, тАЬhuman cold adaptation in the form of increased metabolism and insulation seems to have occurred during recent evolution in populations, but cannot be developed during a lifetime in cold conditions as encountered in temperate and arctic regions.тАЭ

In fact, a lifetime of cold exposure may even backfire: thereтАЩs some evidence that people who do a lot of cold-inducing activities like open-water swimming actually end up with worsened ability to keep extremities like their toes warm. It may be possible to prompt some minor metabolic changes with deliberate cold exposure, and the authors of the new review do float the idea of cold water immersion (i.e. ice baths) for athletes whoтАФlike Mexican soccer playersтАФrarely encounter cold environments but have an important competition there. My personal hunch, though, is that, unlike other environmental stressors like heat and altitude, the Edmonton advantage was primarily mental rather than physical.

Wear a Merino Base Layer

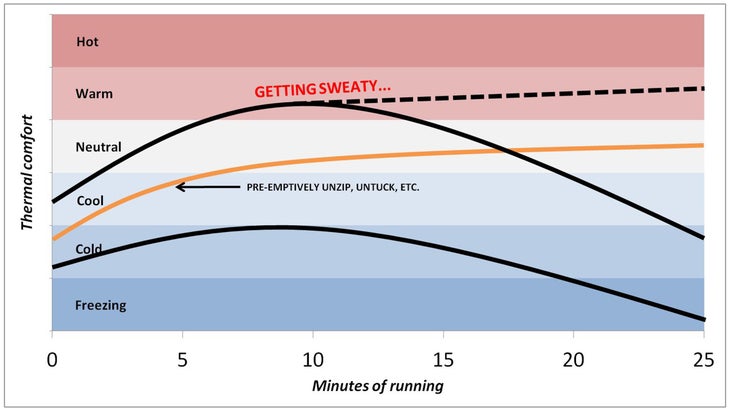

The primary scientific conclusion of the 163 references cited in the review is that you should really try to dress properly when itтАЩs cold. ThatтАЩs the best defense weтАЩve got. In particular, for sustained exercise, you should start out being тАЬcold-uncomfortableтАЭ in the early stages of a workout, since metabolic heat production from exercise will soon make you тАЬwarm-comfortable,тАЭ and overheating will make you sweat which will ultimately drag you back down to тАЬcold-uncomfortable.тАЭ This was the main theme of my article on how to handle winter running, from which I reproduce this highly scientific graph:

Interestingly, the authors of the review turn out to be big fans of merino base layers, citing research that finds them to have тАЬgreater thermal insulation properties and water absorbency than synthetic underwearтАЭ when worn against the skin. The science doesnтАЩt look all that convincing to me, but anecdotally IтАЩm fully on board with that: I went merino a few years ago, and now do literally every winter run (as well as a large percentage of cool fall and spring runs) with .

Plan Your Warmup

One of the key goals of a warmup, as the name suggests, is getting your muscles warm. ThatтАЩs a bigger challenge when itтАЩs coldтАФand more importantly, itтАЩs a lot harder to keep them warm between the warmup and the start of the competition. The specific advice here depends on the logistical details of your workout or competition, but the overall theme is finding ways to stay warm for as long as possible before starting. That mainly involves wearing extra layersтАФand the review notes that cross-country skiers often change their base layer right before the competition to get rid of any sweat that accumulated during the warmup. (ThatтАЩs a tactic I also use before cold-weather running races, though I sometimes wonder if I lose more heat by stripping down in the cold than I save by getting a dry base layer on.)

How Exercising in the Cold Affects Your Health

There are some very obvious acute risks to exercising in extreme cold, like frostbite. The most important defense is covering exposed skin: at the ski race in Ruka, many of those who chose to compete had specially designed tape on their nose and cheeks to protect themselvesтАФsomething IтАЩd never seen before. (Check out the pics : itтАЩs quite a colorful sight!)

There are also some potential long-term implications. Prolonged heavy breathing of dry air can irritate the airways, and eventually lead to an asthma-like condition called , or EIB, characterized by coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath during or after exercise. Since cold air canтАЩt hold as much moisture as warm air, itтАЩs always dry, so winter athletes are at much greater risk of EIB than summer athletes. A study of the 1998 U.S. Winter Olympic team found that 23 percent of them had EIB, including half of the cross-country skiers.

To prevent symptoms, the review suggests several different asthma medications, including salbutamol, salmeterol, and formoterol, all of which are (within certain limits) permitted by anti-doping rules and have not been shown to enhance performance in healthy athletes. This is an important point, because there has been lots of criticism of endurance athletes for having a high rate of asthma medication useтАФfor example, when Norway sent to the last Winter Games. ThereтАЩs an interesting and nuanced debate to be had about what constitutes тАЬathletic enhancementтАЭ versus treatment of a legitimate medical condition. But I think critics have sometimes missed this straightforward explanation for why so many endurance athletes are prescribed asthma meds.

Of course, the preferable approach is to avoid damaging your airways in the first place. The risk of EIB if youтАЩre doing prolonged hard exercise at temperatures of around 5 degrees Fahrenheit or below, according to Michael Kennedy, a researcher at the University of Alberta and one of the reviewтАЩs co-authors. But dryness, rather than cold, is the main trigger, so you might run into problems even in warmer temperaturesтАФincluding indoorsтАФif the air is particularly dry. If you notice symptoms like coughing and wheezing during or after a workout, take steps to moisten the air youтАЩre breathing. For starters, you can use a scarf or balaclava either over or in front of your mouth. I have an old neck warmer that sits a few inches in front of my mouth and creates a moist little microclimate without getting ice all over my face.

There are also more sophisticated options like heat-and-moisture exchanging masks, deliberately designed to warm and moisten air while allowing you to breathe hard enough for exercise. The review notes some research on a model called the . Unfortunately, itтАЩs not perfect: a published earlier this year found that performance was hurt by 1.4 percent in a four-minute all-out running time trial, with slightly lower muscle oxygen and hemoglobin levels while wearing the mask. I actually donтАЩt think thatтАЩs a big problem: you breathe way harder during a four-minute race than you would during, say, an hour-long training session. And the study used AirTrimтАЩs тАЬsportтАЭ filter, which is designed for training, rather than one of their three тАЬracingтАЭ filters, which have progressively lower breathing resistance. All of which is to say that, if youтАЩre doing long training sessions in extreme cold and having some respiratory symptoms, IтАЩd give one of these masks a try.

As for the skiers in Ruka, the rules dictate that a temperature below -4 Fahrenheit, taken at the coldest point on the course, triggers cancellation of the race. (and contrary to NiskanenтАЩs claim that it was -9.4 Fahrenheit), officials measured that temperature at -1.5 Fahrenheit, so the race went ahead. Either way, thatтАЩs pretty cold. ThereтАЩs a decent chance IтАЩll end up going for an easy run in conditions like that sometime this winter. But racing? No, thanks.

This story has been updated to include information from Michael Kennedy.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .