Imagine heading out for an easy jog, but with the feeling in your legs magically altered so that they burn with the pain you would normally experience at a much faster pace. Nothing else is affected: your heart rate remains low, your breathing is untroubled, your mind is sharp. How would this impact your ability to continue? Would you be able to keep going for as long as you normally can, or would the pain force you to stop early?

That’s the basic question posed in , from the research group of Alexis Mauger at the University of Kent in Britain. He induced heightened pain using an injection of hypertonic saline (water that’s saltier than blood) in the thigh, then tested the endurance of his subjects’ leg muscles. The basic result may seem obvious: the subjects quit sooner when they were in more pain. But the interesting question—and the answer is not as obvious as it may seem—is: Why?

For a long time, I didn’t think much about the vocabulary I used to describe what the crux of a hard race or workout feels like. It’s difficult and painful and exhausting; you’re drowning in acid or piggybacking a bear or (my go-to) “rigging” (to rig being the unofficial verb form of rigor mortis). But those words don’t all mean the same thing. Do you really stop because it hurts too much? Or is there something else that makes you incapable, or at least unwilling, to continue?

These are deep waters and difficult questions, which, once I started wondering about them, turned out to be so interesting that I ended up writing about them a few years ago. But one distinction that’s much clearer to me now is the difference between effort, which researchers sometimes define as “the struggle to continue against a mounting desire to stop,” and pain, which, in the context of exercise, we can define as “the conscious sensation of aching and burning in the active muscles.”

Back in 2015, I saw a conference presentation by a researcher named Walter Staiano that contrasted these two sensations. The data he presented that day was eventually . In one experiment, he and his colleagues asked volunteers to plunge their hands in ice water until they couldn’t tolerate it anymore, rating their pain on a scale from zero to ten every 30 seconds. As you’d expect, pain ratings climbed steadily until they approached the maximum value (peaking at 9.7, on average), at which point the volunteers gave up. In the ice-water test, pain is the limiting factor.

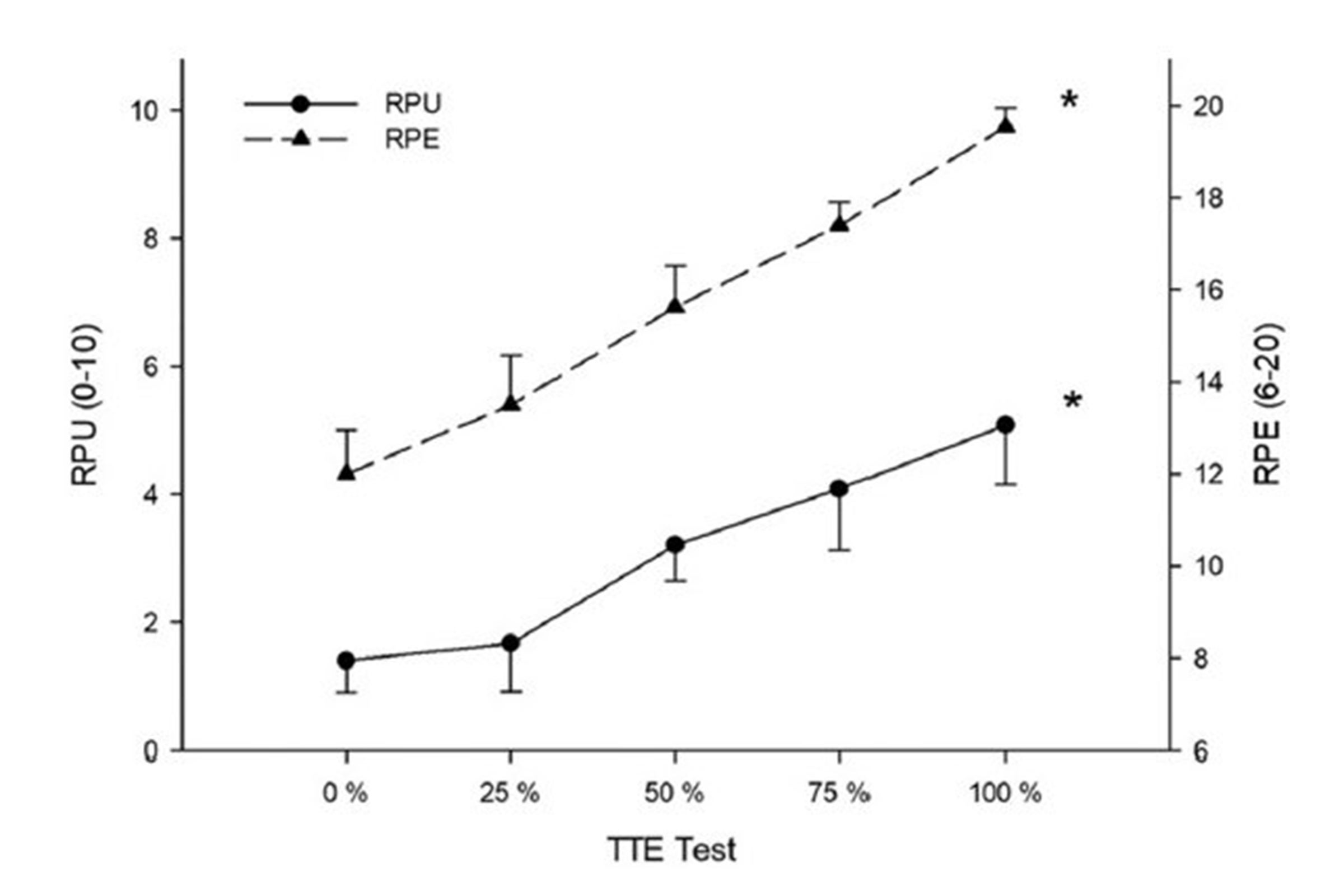

Then, with this experience of what ten-out-of-ten pain feels like, they performed a cycling test to exhaustion, rating both their pain and their sense of effort (on the Borg scale, which runs from 6 to 20) once per minute. As the study explains, “participants were reminded not to mix up their ratings of the conscious sensation of how hard they were driving their legs (an important component of overall perception of effort during cycling) with the conscious sensation of aching and burning in their leg muscles (muscle pain).”

Which one is the limiting factor? As the cycling test progressed, both pain and effort drifted steadily upward. On average, by the time the subjects gave up, their pain rating was 5.0 out of 10. That corresponds to “strong” pain but is still a long way from the near maximal values they experienced in the ice-water test. Effort, on the other hand, got all the way to 19.6 out of 20 on average. It’s tempting to conclude that the subjects quit because their effort was maxed out.

Here’s what the data from the cycling test looks like. The pain ratings (RPU), shown on the left axis, are drawn with circles and a solid line; the effort ratings (RPE), shown on the right axis, are drawn with triangles and a dashed line. The horizontal axis shows the passage of time, scaled to the eventual point where each subject gave up.

Based on this experiment and others like it, I’ve been converted to the view that your subjective perception of effort is more important than pain in dictating your limits. That doesn’t mean pain is irrelevant. There’s no doubt hard exercise hurts, and that pain may indirectly influence your performance. For example, Staiano and his colleagues suggest that coping with pain demands inhibitory control, a cognitive process that may fatigue your brain in ways that increase perception of effort. In this view, you don’t quit because the pain becomes intolerable, but the pain is one of several factors that pushes your effort to its tolerable limits.

Not everyone agrees, though. Mauger, a former colleague of Staiano’s at the University of Kent (Staiano has since moved to the University of Valencia, in Spain), has published a number of studies in recent years exploring the idea that pain itself can be a limiting factor in endurance. The main goal of his new study was to establish a protocol that would allow him to modify pain while keeping other factors like exercise intensity constant. You can’t just ask subjects to exercise while poking them with sticks or dipping their hands in ice water, because that’s not how we experience pain during exercise.

The good news is that hypertonic saline injections seem to work. The exercise protocol in the study was an isometric knee extension, which basically involves trying to straighten your knee against an immovable load. Comparing a heavy resistance (20 percent of maximum torque) to a light resistance (10 percent), with the addition of the saline injection, his 18 subjects couldn’t detect any qualitative differences in the pain they experienced. The injection made the light load hurt in the same way as the heavy load. This opens the door for some interesting future experiments in which researchers alter pain without changing any other physiological parameters, hopefully in realistic activities like cycling and running.

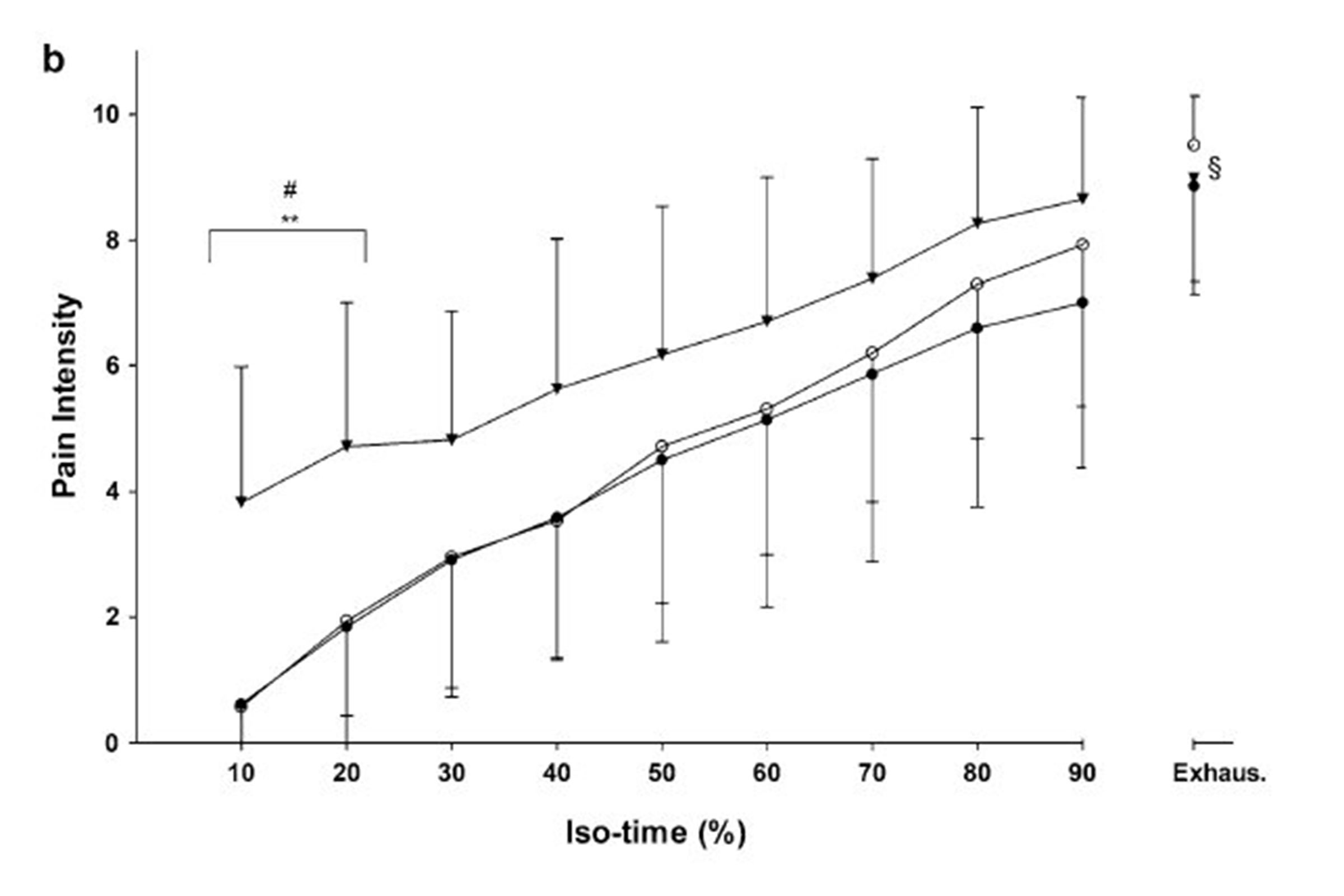

For now, the researchers compared three different variations of the knee-extension test, with subjects pushing against a 10 percent load until they couldn’t sustain it anymore, which typically took a little less than ten minutes: once with no injection (shown below with open circles), once with the painful injection of hypertonic saline (triangles), and once with a placebo injection of weaker saline that didn’t cause pain (closed circles).

The pain graph is fairly straightforward. The subjects report higher pain right from the start of the test, and it stays high. Eventually, everyone reaches a near max value of pain before giving up, but the hypertonic-saline group maxes out more quickly (448 seconds, on average), presumably because it started at a higher value. In comparison, it lasted 605 seconds with the placebo injection and 514 seconds with no injection.

From Mauger’s perspective, this looks like a smoking gun, showing that “muscle pain has a direct impact on endurance performance.” The theory is that the salt in the injection triggers feedback through certain nerve fibers known as group III/IV afferents—the same nerves during hard exercise. That’s why the sensation of pain mimics the feeling of harder exercise. Eventually, it reaches a point where the pain becomes intolerable, and you stop or slow down.

But how do we reconcile Mauger’s results with Staiano’s? Mauger’s subjects only gave up when pain was maximal; Staiano’s subjects gave up when pain was just five out of ten. I suspect that has a lot to do with the choice of exercise protocol. Mauger’s subjects were sitting in a chair trying to straighten their right leg. They weren’t out of breath or even moving. Just as in the ice-water challenge, it’s not hard to believe that pain was one of the dominant sensations they felt. Staiano’s subjects, on the other hand, were cycling, with all the other feelings and sensations that entails. Most of what we do in real life looks more like cycling than leg straightening or ice-water challenges.

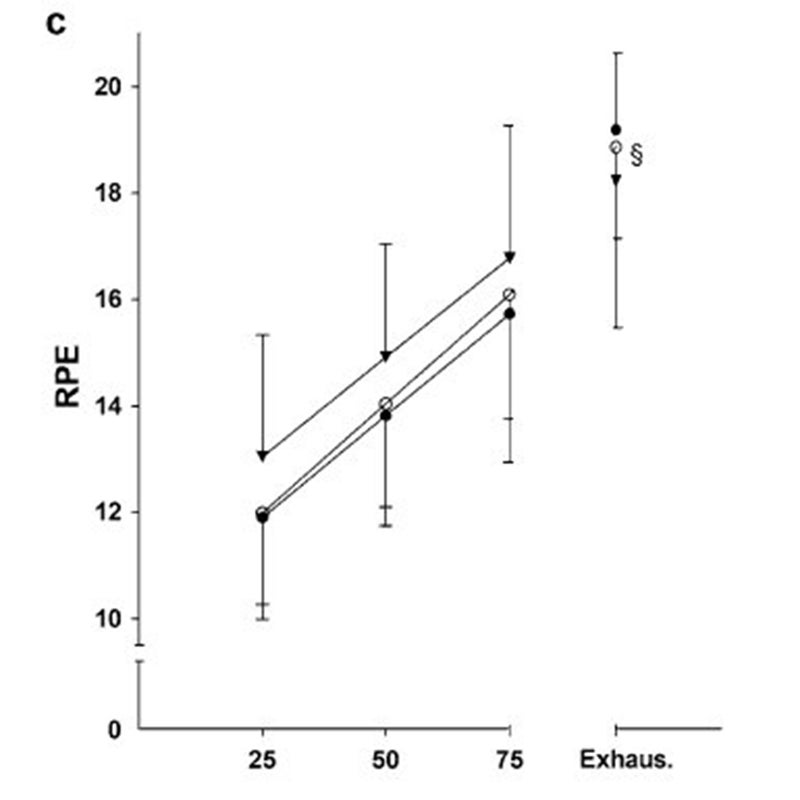

It’s also worth taking a look at how Mauger’s subjects rated their perception of effort. He doesn’t spend much time discussing it other than to note that there were no significant differences in perception of effort between the groups at any time point. This seems like a blow to Staiano’s suggestion that pain may influence endurance by increasing perception of effort. But take a look at the actual data for perception of effort (RPE, on a scale of 6 to 20):

As expected, effort increases steadily throughout the test. And while there’s no statistically significant difference, it certainly looks as though the hypertonic-saline group (the triangles) has higher effort ratings throughout the test. At exhaustion, the subjects are somewhere around 19 on the effort scale, which is pretty close to maxed out. The data in this study isn’t sufficiently detailed to answer the question one way or the other, but in my view, it doesn’t rule out the theory that pain matters mainly because it changes your sense of effort.

If, at this point, you have the sense that we’re trying to classify invisible angels on the head of a pin, that’s understandable. Something makes us slow down, whether we call it effort or pain. But for me, blaming pain for my inability to race faster never felt quite right. Sure, there were lots of times when I . But there were also times when I successfully ignored the pain, and yet I still eventually encountered the feeling that I couldn’t go any faster. So for now, I remain in Staiano’s camp—if only because that’s how I prefer to remember my glory days.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .