Meet Lazarus Lake, the Man Behind the Barkley Marathons

What kind of sadist creates the hardest race in the world? We sent our writer to find out.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Around 10 A.M., Gary Cantrell��saw a turtle in the middle of the road. “We gotta get there before a car does,” he said, pointing at the small green-yellow shell a dozen yards ahead of us in the westbound lane of Nebraska’s Highway��20. The cattle prod he was using as a walking stick tapped against the asphalt as he made slow, steady headway along the shoulder.

Both pinky toes poked out of holes in Cantrell’s running shoes. Above white crew socks peeked a few inches of tanned calves. With a painful moan, he bent down and scooped up the animal, then righted himself and shuffled across the road, where he set the turtle in the long grass. “I take them the way they’re headed,” he said, “or they’ll just turn around and walk back.”

This patch of sandhills and hay bales just east of Valentine��marked the roughly 1,800-mile point in that Cantrell had begun two months earlier in Newport, Rhode Island. Many people who cross the country on foot run 40 to 50 miles a day and finish in two or three months. Cantrell was averaging��27 miles a day��and would take four months to finish.

The previous night, I had driven up from my home in��New Mexico to meet him at a Super 8 motel, where I found him seated next to a half-empty box of pizza, applying benzoin and bandages to his feet. “It’s a mystery to me why you want to write about my transcon,” he said. “It’s kind of a pathetic attempt. I’m an old, beat-up man who doesn’t have a lot left in the tank.” He cut a pea-shaped piece of moleskin and pressed it into the ball of his foot.

But Cantrell is not just any old man. He is the mastermind behind arguably the world’s toughest footrace: the Barkley Marathons.��Though��you might know him by a different name: Lazarus Lake.

Every year on the closest Saturday to April Fools’��Day, about 40 hand-picked runners line up behind the yellow metal gate that marks the entrance to northern �ձ�ԲԱ�������’s . Cantrell stands on the other side of the gate with a fresh Camel in hand. With a quiet flick, he lights the cigarette and lets out a stream of smoke: the signal that the race has begun. Over the next 60 hours, runners will attempt to complete five laps on a 20-mile course through the mountainous, forested park. More than 98 percent will fail.

The Barkley Marathons is unlike any other ultramarathon��in the world. On the surface, 100 miles in 60 hours might seem reasonable. , one of the country’s most difficult��and most prestigious ultras,��has a time cutoff of 48 hours. But the Hardrock course has 33,000 feet of cumulative elevation gain and follows designated trails. The Barkley has almost double the climbing and is largely off-trail. It is part trail race, part orienteering challenge. Since it began in 1986, the event��has been attempted by more than��1,000 people, some multiple times. Just 15 have finished.

Frozen Head is known for its steep topography, inch-long saw briars, relentlessly��cold rain, and disorienting fog. The park butts up against Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, a now defunct maximum-security facility that was once home to criminals like James Earl Ray, who assassinated Martin Luther King Jr. Stone buildings and barbed wire were the warden’s primary defenses, but it was the surrounding mountains and thick vegetation that ensnared Ray when he and six other convicts jumped the wall in 1977. Police found Ray and his cohorts two and a half days later, a mere eight miles from the penitentiary.

The Barkley started almost nine years later, largely in response to��Ray’s failed escape. Cantrell heard the news and figured he could cover 100 miles in the same amount of time. He couldn’t. .

To be fair, Cantrell doesn’t make it easy. Maintained trails do exist��in Frozen Head State Park, but the Barkley barely makes use of them. Instead, participants use a map and compass to navigate Cantrell’s specified route up brushy��climbs and across creeks. Cantrell hides 13 books along the course. Runners have to tear out the pages corresponding to their bib number to prove they completed the whole loop (they get a new bib for each circuit).

The Barkley’s history is one of close calls and failures so spectacular they almost don’t seem real. In 2006, got lost on loop one and stumbled all the way into the next county before finding his way back to��the start��32 hours later. In 2005, the same year he set a speed record on the Appalachian Trail,��Andrew Thompson got to a book drop partway through loop five and was so out of it that he forgot why he was there. He walked back to the park entrance and called it quits.

In 2017, a half-hour after local runner��John Kelly became the Barkley’s 15th finisher, Canadian pro��Gary Robbins collapsed in front of the yellow gate that marks the finish—just six seconds over the cutoff. Only, he’d come from the wrong direction, having taken a wrong turn in the final miles. He lay on the ground soaked, shivering, and desperately mumbling, “I have all my pages.”

Stories like these have captivated even nonrunning audiences��and launched the Barkley—and Cantrell along with it—into somewhat unlikely fame. Mainstream media outlets like the ��and ��have written about the race, and in 2014, the event was the subject of��. At the center of it all is Laz, as runners call him, the bearded, potbellied figure presiding over the sufferfest with his pitbull, Big, at his feet and a Staples Easy Button for participants to press at the finish. It’s common knowledge that he lies about the actual race distance, which Barkley veterans hypothesize is closer to 120 or 130 miles. He has told countless female competitors that he doesn’t think a woman can finish his race, because, by his calculations, women’s finishing times across the sport of ultrarunning��are��on average 12 percent slower than men’s. Add 12 percent to the fastest Barkley finishing time, he argues, and you don’t come in below cutoff. (By that math, Brett Maune’s 2012 course record of��52 hours��3 minutes��and 8 seconds would actually lead to a woman finishing��well under the 60-hour cutoff, but Cantrell says that “only Maune has a time in that range.��It would��take a true outlier.”)

As runners trickle in with drooping faces, tattered clothing, and dilapidated feet, Cantrell taunts them with jokes. “I remember talking with him after my third loop,”��Kelly says of his first Barkley attempt, in 2015. “He said something like, ‘Well, it’s pretty much just a formality from here. You’re almost there.’” Kelly had 40 miles and about 24,000 feet of climbing ahead of him. He never finished loop four. The following year, he made it through to the first few hundred yards of loop five before falling asleep on the side of the trail in a spot now dubbed Upper Kelly Camp. Runner had a typical attitude coming into her first Barkley last year, telling me that she “wasn’t quite sure whether I should view Laz as a friend or a foe.”��

Cantrell and his wife, Sandra, live in a farmhouse in Bell Buckle, Tennessee, a town an hour south of Nashville with a population of 532. Their property is dotted with rock walls Cantrell built in the garden and trails he made��in the woods. “We were hippies in a sea of accountants,” says Sandra, who Cantrell met in the accounting program at Middle Tennessee State University in the late seventies. Cantrell wore his curly��blond hair in a ponytail and sat in the far back of the classroom. Every time Sandra turned around, he would wink, tilt his head to the side, and stick out his tongue. ��

These days they have three grown kids, a few grandkids, Big the pitbull, and a Jack Russell mix named Little. Sandra prepares people’s taxes for a living. Before Cantrell retired in 2011, he ran the books for a manufacturing company and the city government in the neighboring town of Shellbyville. Neither one of them tells me their real age, because they’re afraid of getting their identities stolen. Though Cantrell has a more interesting answer for those who pry. “Age for me is the mileage on my body,” he says. By that measure, he’s ancient.

Running has been a part of Cantrell’s life practically since he can remember. His father grew up in Oklahoma on the farm next��to Andy Payne, winner of the 1928 , a short-lived cross-country race from Los Angeles to New York. Growing up in Tullahoma, Tennessee, Cantrell and his brother, Doug, were regaled with stories of Payne’s famous run.��

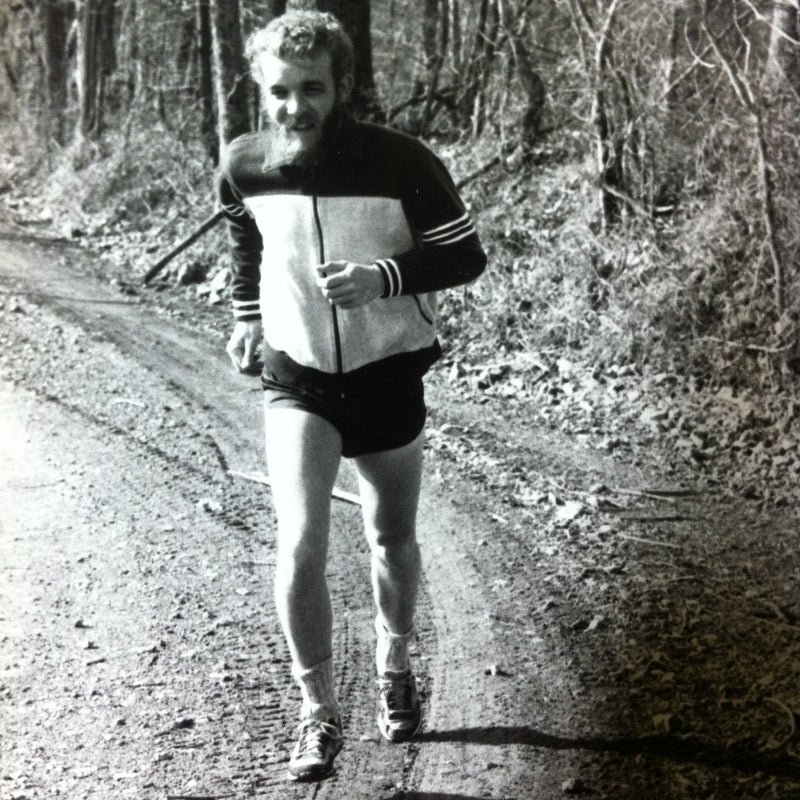

Cantrell himself started running in 1966, the same year he started smoking. He was in middle school (this would put him in his mid-sixties��now, if he’s telling the truth), and his father had started running a mile a day on the local track. Young Gary tagged along. “It was the first thing I could beat him at,” he says. When he entered high school, Cantrell joined the cross-country and track teams, breaking five minutes for the mile by his senior year.

“I liked the training, I liked the atmosphere, and I liked the people,” he says. More than anything, he relished the competition.��After graduation, he moved to the city of Memphis and became the 12th��member of the local running club. Every Saturday, the club held a race. “We’d meet at the Memphis state building, pick a course, and hide a stopwatch in the bushes,” Cantrell says. “Whoever got back first pulled out the stopwatch and called out everybody else’s times.” �����ԹϺ��� of these club events, Cantrell entered any race he could find—local 10Ks, all-comers track meets, and, soon, marathons.

“Age for me is the mileage on my body,”��he says. By that measure, he’s ancient.

In a letter to a friend written shortly after his first 26.2 miles, at �ձ�ԲԱ�������’s Andrew Jackson Marathon in 1975 or ’76 (he can’t remember), Cantrell recalls waking four hours before the 8 A.M.��race start to “get ready and [eat] five ham sandwiches for stability.” He finished in 3 hours 20 minutes. “I felt so proud I was so ecstatic what a thrill I had done it,” he wrote. “A marathon, wow, incredible. You really ought to try it once it is unreal it was one of the highlights of my life.”

By the time he found his way to Middle Tennessee State University in 1979, he was running multiple marathons a year and covering 80 to 100 miles a week, with 120- or 140-mile weeks in the lead-up to big races. Often��he ran farther than 26.2 miles in training.

In 1979, ultramarathons were few and far between, and 100-milers even more so. Gordy Ainsleigh’s Western States Endurance Run, in California, was just two years old. There were no ultra-distance races in Tennessee. With school and, soon, work and kids in the picture, frequent travel was not an option. So Cantrell found challenges closer to home.

One��October Saturday in 1980, he set out to run 100-plus miles from Alabama to Kentucky up Highway 231. He wore shorts, shoes, a T-shirt,��and a nylon windbreaker with some cash in the pocket. “You just had to run really quick,” he says, “to get to the next store before you got too thirsty.” He covered the first 64 miles in 12 hours and 14 minutes, rushing to get to a bar where he could watch the Oklahoma-Texas football game on TV, but he quit at mile 93 after a freezing rainstorm left him futilely stuffing newspaper into his clothes for insulation.

The next fall, Cantrell returned with friends and ran the whole route in a little over two days. With that, cross-state “journey runs,” as Cantrell called them, became an annual tradition. “We ran from Knoxville to Nashville a time or two,” he says. “Then we ran from Cumberland Gap to Nashville. We ran from different places to different places.” To maintain the adventure of a multi-day run, every time someone finished under 24 hours, Cantrell found a new, longer route. Ultimately, he settled on a 500-kilometer line cutting diagonally across Tennessee from Missouri to Georgia, which became the Last Annual Vol State��Road Race. The event took place in July, with a time cutoff of ten days, so that anyone willing to endure for that long would be able to finish. There were no aid stations, nor dedicated stages: participants ate wherever they found food and slept whenever they could, in parks and parking lots. To this day, the event is held under the same conditions.

The Vol State was not the first race Cantrell created, nor would it be the last. There was the Strolling Jim 40, the Nick Marshal 24-Hour track race, the Two-Bit Marathon, and the Idiot’s Run, a 123-mile race entirely on gravel roads “that would torture your feet.” More recently, he’s started a new track race,��called , and the��Big��Backyard Ultra, a last-man-standing event where competitors loop a 4.1667-mile trail every hour. Whoever lasts the longest wins. Everyone else receives a DNF. But by far the hardest and most well-known race Cantrell has dreamed��up is the Barkley.��

On April Fools’��weekend in 1986, Cantrell went down to Frozen Head with some friends to attempt a new course he and his pal Karl “Raw Dog” Henn had mapped out in the woods where Ray had attempted his escape. The course initially consisted of several smaller loops totaling 50-plus miles. No one finished in the alloted 36 hours. But the next year��they all came back.

Sandra remembers these early years as big family reunions, a rare opportunity for the far-flung ultra community to reunite. By then��the Cantrells had a trio of young kids, and every April��the five of them traveled to Frozen Head. Babies fidgeted in playpens��and toddlers ran around in the dirt while Cantrell and his peers went to battle in the woods.

“They were just doing this run for fun,” Sandra says. “It was about getting people together and having a great weekend.” The fact that no one could finish—yet—wasn’t a deterrent. It was the reason for the race’s existence. Even in the mid-eighties, when ultrarunning was in its infancy and covering 100 miles was still considered the frontier of human endurance, Cantrell felt the sport lacked true challenge. Then, and even more so now,��most races were entirely within the range of reasonable human accomplishment, and finishing was simply a matter of determination. Few, if any, races afforded runners the opportunity to find their absolute limits.

“It’s easy to design an impossible race, and it’s easy to make a race everyone can finish,” Cantrell says. “It’s really hard to find that point where impossibility is just so close.” The Barkley was, and has always been,��the pursuit of that line. It was doable, he thought, but only for the very best runners—a true test of human athleticism, skill, and fortitude.

The first man to fit the bill was “Frozen” Ed Furtaw, who completed the fiftyish mile course in 1988. The following year, Cantrell doubled the official distance to 100 miles��and dubbed the first half a fun run. (The course has since changed many times. The 100-mile race now consists of five loops, and��the 60-mile fun run is three loops.)

“What makes the Barkley so unique in the world is the fact that when someone succeeds, he makes it tougher,” Furtaw says. “He wants to keep it at the limit of possibility.” Over the next six years, several more people completed the fun run. In 1995, British runner Mark Williams staggered to the yellow gate in 59 hours 28 minutes, becoming the Barkley’s first 100-mile finisher. The course changed, too, incorporating additional climbs and descents.

“It’s easy to design an impossible race, and it’s easy to make a race everyone can finish,”��Cantrell says. “It’s really hard to find that point where impossibility is just so close.”��The Barkley was, and remains, the pursuit of that line.

Despite the hours Cantrell spent bushwhacking through the park, mapping new parts of the route, he never expected��many��people to be interested. “I didn’t think people would give the Barkley a chance,” he says, “I didn’t think that people would say, Yeah, let’s go put ourselves through the excruciating limits of endurance and think we’re going to fail for multiple days, because it’ll be so great.” He was wrong.

Within a few years, Cantrell had to institute a wait list to accommodate the thousand or so people��that were clamoring to sign up for his race each year.��In 2014, he created the Barkley Fall Classic, a 50K mini Barkley to give fans and wannabe Barkers, as race participants call themselves,��a taste of the real deal. These days, he’s had to go to extreme measures, like switching up the start date without warning, which��deters interested bystanders and keeps the race’s footprint small. The race-entry process is kept secret. (Figuring out Cantrell’s e-mail address and sending him the required application materials at the right time on the right day is “part of the game,” says Barkley veteran , who has attempted Barkley twice��but never finished.)��It’s a process that favors doggedness and respect for the race’s culture as much as a fat resume of fast ultra finishes.

In some ways, runners today have an advantage over those who attempted the Barkley in the eighties��and nineties. Back then, running headlamps, hydration vests, and endurance gels didn’t exist, let alone lightweight, technical shoes and apparel. So Cantrell has done his best to counteract the benefits of modern gear. Participants are not allowed to use pacers or GPS watches. Instead, he��hands out $11 timepieces from Walmart. The only on-course aid comes in the form of a few gallon jugs of water stashed along the route. Success requires speed and endurance, yes, but also navigational prowess, grit, a mind for problem-solving, and the ability to keep it together after more than two full days and nights without sleep.

From the outside, it might look like the vast majority of runners at the Barkley are failing. Cantrell doesn’t see it that way. “Your job as a race director is to provide a platform for runners to find greatness in themselves,” he says. “Everyone can find success within the process of discovering what they’re capable of. If they do that, they walk off feeling a winner.”

It’s a mentality he picked up through 30 years of coaching middle school��and high school basketball. “Coaches do a lot of good,” he says. “Sports are the place where you get introduced to the real world. It’s where you learn that everyone is not going to succeed, that you have to work for what you get, and that the other team is trying to win, too.” Like any good coach, Cantrell is in the business of presenting athletes with seemingly insurmountable challenges, not in the hope that it will break them��but on the certainty that it will make them stronger. “Every runner who signs up for a race is a star,”��he says. Whether the the individal wins, finishes, or DNFs��does not matter. Their journeys toward new personal limits are as meaningful to Cantrell as his own were decades ago. “The important piece is not necessarily whether you fail or succeed,” says Kelly, “but how far you were able to get and what you found out about yourself in that process. That’s an opportunity that’s difficult to find elsewhere.”

It’s been years since Cantrell has been able to run competitively. He’s had a bad back since the eighties, the result of a herniated disk, and a few years ago he suffered a complete blockage of the femoral artery in his left leg and was diagnosed with Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disorder. But his passion for traveling long distances on foot has not diminished.

“A lot of people would not consider this fun,” he said as we wandered down Highway 20 at two miles per hour. “I’ve had people ask me, ‘What made you want to do it?’ and my answer is that I can’t really imagine anyone not wanting to do it. How could you ever look at the map and not wonder what it would be like?” Dressed in a flannel and a straw hat, with double-bridged glasses perched above Santa Claus cheeks, he looked more like an aging Huck Finn than the mean old man I’d anticipated based on the stories I’d gathered. In his clear, soft tone, I heard the excitement of the twentysomething who took off across Tennessee on foot just because it sounded fun.

During the night and day that I walked with him, he seemed to subsist on pizza, Dr��Pepper, and cigarettes. The only green things I saw him eat were pistachios.��He’s missing 13 teeth, which he pulled out himself as they rotted in order to avoid dentist fees.

The disparate parts of his personality—the accountant named Gary who’s suspicious of having his identity stolen and the “hillbilly”��(his word) Barkley creator named Laz—are difficult to reconcile.

According to Cantrell, Laz is just a nickname. The story he tells is that he found it in a phone book while on a journey run in the eighties. Ten years later, he used it to sign up for his first e-mail address, to avoid using his real information. The moniker stuck, and as Barkley began to gain popularity, it became a sort of race-director nom de guerre.

Some runners think that Laz is an intentional construct, something Cantrell uses to separate himself from the Barkley’s brutality or to add to its mystery. “He’s built this persona, and people latch on to it,” says Beverly Anderson Abbs, a longtime Barkley participant who’s finished two fun runs.

Ultimately, Cantrell seems to enjoy��giving people something to puzzle over. “Wrong information out there is OK,” he said. “It just makes the truth harder to find.”��

He says he doesn’t waste much time worrying about what other people think of him. When I asked if there was anything about himself that he wished people knew, he responded with a low, breathy laugh. “Why would they care?” he said. “In the end, all the races are about the runners. I’m not important.”