When an athlete reaches the podium despite a prior medical event—a cancer diagnosis, say, or a car accident—we consider it a triumph of the human spirit. When a bunch of athletes do so, and all of them have suffered the same setback, we can be forgiven for wondering what’s going on. According to the International Olympic Committee, roughly one in five competitive athletes suffers from exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, or EIB, an asthma-like narrowing of the airways triggered by strenuous exercise. The numbers are even higher in endurance and winter sports. Puzzlingly, studies have found that athletes with EIB who somehow make it to the Olympics are more likely to medal. What’s so great about wheezing, chest tightness, and breathlessness?

The answer isn’t what you’re thinking. Sure, it’s possible that some athletes get a boost because an EIB diagnosis allows them to use otherwise-banned asthma medications. But there’s a simpler explanation: breathing high volumes of cold or polluted air dries out the airways, leading to an overzealous immune response and potential long-term damage. “It’s well established that high training loads and ventilatory work increase the degree of airway hyper-responsiveness and hence development of asthma and EIB,” explains Morten Hostrup, a sports scientist at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. In other words, the athletes who train hard enough to podium are more likely to develop EIB as a result.

That trade-off might be worthwhile if it means competing at the Olympics. For those of us who simply enjoy spending our winter days vigorously exploring the outdoors, the risk of EIB remains mostly unknown territory. Activities with the highest risk involve sustained efforts of at least five minutes, particularly if they take place in cold or polluted air. Cold air doesn’t hold much moisture, so it dries the airways. This affects skiers, runners, and triathletes, among others. Indoor environments like pools and ice rinks are also a problem, because of the chloramines produced by pool water and exhaust from Zambonis. As a result, swimmers, ice skaters, and hockey players are also at elevated risk of EIB. Over time, repeated attacks can damage the cells that line the airways.

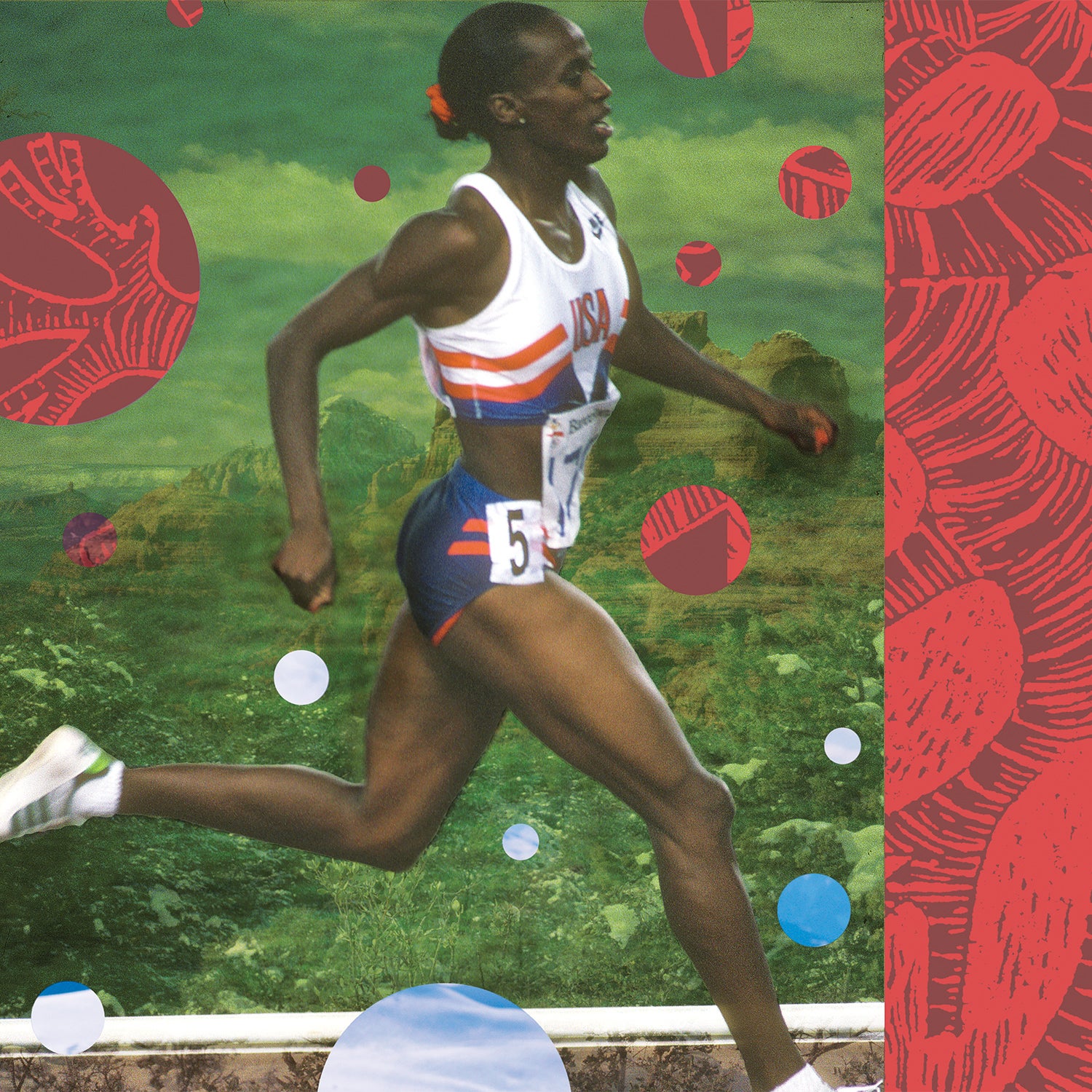

Unfortunately, many athletes develop symptoms of EIB without realizing the underlying problem. After all, the feeling that you can’t catch your breath is pretty much written into the job description of most endurance activities. But starting in the 1990s, sports scientists began to suspect that top athletes had more breathing problems than would be expected. Before the 1998 Winter Games, U.S. Olympic Committee physiologists examined Nagano-bound athletes to see whose airways showed abnormal constriction in response to arduous exercise. Almost a quarter of the athletes tested positive, including half the cross-country ski team.

One reason EIB often flies under the radar is that the usual diagnostic workups aren’t challenging enough to provoke an attack in conditioned athletes. Among the accusations against disgraced coach Alberto Salazar was that he showed athletes how to fool EIB tests to get permission to use asthma meds. “He had a specific protocol,” star 5,000-meter runner . “You would go to the local track and run around the track, work yourself up to having an asthma attack, and then run down the street, up 12 flights of stairs to the office and they would be waiting to test you.” Salazar certainly gave some shady advice, including encouraging Fleshman to push for the highest possible dosage of medication. But his tips for gaming the asthma test were similar to what USOC physiologists advocate, and published last spring also concluded that more intense exercise challenges are better for diagnosing EIB in conditioned athletes. If you’re really fit, in other words, the rinky-dink treadmill in the doctor’s office isn’t going to push you hard enough.

If you do get an EIB diagnosis, your doctor can prescribe asthma medication, including inhaled corticosteroids like fluticasone and airway dilators like salbutamol. If you’re an elite athlete subject to drug testing, you’ll need to tread carefully, since some of those medications are either banned or restricted to a maximum dosage. Hostrup and his colleagues note that there’s also evidence that fish oils high in omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C, and even caffeine might help reduce EIB symptoms. And on the non-pharmaceutical side, you can minimize the chance of an attack by doing a thorough warm-up of 20 to 30 minutes, including six to eight 30-second sprints. This can temporarily deplete the inflammatory cells that would otherwise trigger an airway-narrowing attack.

The best outcome of all, of course, is to avoid developing the problem in the first place. In 2008, I interviewed a Canadian military scientist named Michel Ducharme, who told me stories of cross-country skiers swallowing Vaseline in an attempt to protect their airways from the cold. This is a terrible idea on many levels—and, he assured me, totally unnecessary. Air warms up very quickly when you inhale it, so there’s no risk of freezing your throat tissue. But dryness is another question, and scientists have reconsidered whether some kind of protection—just not Vaseline—could be useful if you’re going hard on cold days.

One option is a heat-and-moisture-exchange mask, which warms and moistens the air you inhale. A company called AirTrim makes them with a range of levels of resistance for training or racing. Several studies have found that this type of mask seems to reduce EIB attacks. Research by Michael Kennedy at the University of Alberta found that EIB risk increases significantly when temperatures drop below about five degrees Fahrenheit. The precise threshold depends on conditions and individual susceptibility, so if you start coughing or wheezing, that’s a sign your airways are irritated. If you don’t have a breathing mask, a scarf or a Buff over your mouth can offer a temporary solution.

Don’t take all this as a warning against getting outdoors in the winter. I live in Canada, so staying inside when it’s below five degrees Fahrenheit would be a death sentence. But I’m no longer as macho about the cold as I used to be. I wear puffy mittens and merino base layers, and when my snot starts to freeze I cover my mouth and nose. Athletes with EIB may do better than their unimpaired peers at the Olympics, but that’s one edge I can do without.