One of the key articles of faith of modern sports nutrition is that your body can only use a certain amount of protein at a time. Opinions differ on what that amount is. It might be as little as 20 grams; it might be as much as 40 grams, particularly for older adults whose bodies are less sensitive to the muscle-growth-stimulating effects of protein. Maybe it needs to be expressed relative to body size, like 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight, rather than as a fixed number. Those details don’t matter here; the point is that there’s a maximum.

The reason that’s important is that most North Americans eat lots of protein, but don’t spread it evenly throughout the day. A typical pattern might be 10 to 15 grams at breakfast and lunch, then 65 grams or more at dinner. That means that at breakfast and lunch, you’re not getting enough protein to max out the synthesis of new muscle protein. At dinner, on the other hand, you’re getting too much, so the excess will simply be burned for energy. The better solution, according to this logic, is to smooth out your protein consumption so that you’re getting at least 20 grams (or 40 or 0.4 grams per kilogram or whatever) at each meal, adding a protein-rich snack sometime during the day, and perhaps even another one right before bed.

That’s the conventional wisdom. So from researchers at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, led by noted muscle physiologist Luc van Loon (whose vivid, no-nonsense advice I’ve written about previously), has generated plenty of buzz. In short, van Loon’s new data suggests there’s no upper limit on protein after all, and that huge doses of protein—they use 100 grams in the study, because that’s about how much protein they figured they could eat at a barbecue without force-feeding themselves—produce proportionately larger increases in the formation of new muscle.

A Unique Kind of Protein Study

The study involved 36 volunteers split into three groups. They each did a one-hour weight-training workout and then immediately downed a drink containing either 0, 25, or 100 grams of protein. The protein came from the milk of a Holstein cow that the researchers injected with a special carbon isotope tracer. This meant that one of the amino acids in the milk had a slightly different chemical form than usual, enabling the researchers to track the progress of the protein drink as it was digested and incorporated into new muscle proteins in the subjects’ bodies. (I once interviewed one of van Loon’s postdocs about an earlier “glowing cow” experiment, and he described the unexpected responsibilities he had to take on: “My job was to talk to them, brush them, and basically keep them in a good mood,” he recalled. “If the animal becomes stressed, milk production declines, so we treated them like princesses.”)

Anyway, the next part of the experiment basically involved sitting around for 12 hours and taking a bunch of blood samples and muscle biopsies to figure out what was happening in the subjects’ muscles following the exercise-protein combo. That combination is important: both resistance exercise and eating protein boost the formation of new muscle protein, but putting them together within a window of four to six hours produces a muscle-building effect that’s greater than the sum of its parts. The full suite of measurements and analysis is extremely complex (and , if you’re interested), but the most important parameter is how much new muscle protein is being synthesized, because that’s what (more or less) dictates how much muscle you’ll gain over time.

There are two key things about the study. One is the time frame: most previous studies only monitored muscle protein synthesis for six hours or less, so 12 hours provides a much longer window for the effects of a big protein dose to show up. The second is the protein dose: previous studies topped out at 45 grams, so it may have been hard to see big differences compared to, say, 20 or 30 grams.

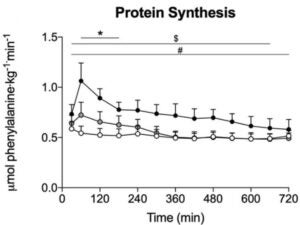

Here’s the key result, showing protein synthesis over the 12 hours following the workout and protein drink. Black circles are the 100-gram group; grey circles are the 25-gram group; and white circles are the 0-gram control group:

The effect isn’t subtle: the 100-gram group is getting way more protein synthesis than the 25-gram group right away. And the biggest difference comes after the six-hour (i.e. 360-minute) mark: by that point, the 25-gram group is back to baseline, while the 100-gram group still hasn’t gone back to baseline even after 12 hours. The extra protein synthesis isn’t exactly proportional—that is, four times more protein doesn’t give you four times the synthesis—but it’s substantial.

What the New Protein Findings Mean for Athletes

There’s a straightforward conclusion here, which is that the idea of a maximum protein dose—at least, one at 40 grams or less—was wrong. You always want to be cautious about chucking away a whole bunch of seemingly settled science on the basis of a single study. But this study seems solid, and it has identified some clear gaps—in duration and protein dose—in the earlier studies that it’s overturning. So let’s assume for now that it’s correct. The question, then, is what it means for how athletes should eat.

For practical purposes, the real apples-to-apples comparison would have been 100 grams of protein versus four doses of 25 grams spaced four hours apart. Which pattern would produce more protein synthesis in that comparison? Nobody knows at this point. There are a bunch of other reasons that I’ll be sticking with three meals a day, including the fact that I really enjoy all my meals. As an endurance athlete, I’m also as conscious of my carbohydrate supply as I am of protein. And even for protein and muscle-building, there are lots of unanswered questions—like whether you’d need to time your workout around your 100-gram protein bomb. If I lift weights in the morning then get all my protein in the evening, or vice-versa, does that still work?

There are certainly people who are into the one-meal-a-day thing, and for these people this is an important result. In their discussion, van Loon and his colleagues note that their findings suggest that time-restricted feeding shouldn’t necessarily lead to muscle loss. For me, the main takeaway is that it’s probably not as important as I once thought to spread my protein perfectly throughout the day. That won’t change how I actually eat, because getting 25 grams of protein at every single meal has always been more aspiration than reality—but at least I’ll feel less guilty about it.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .