Already in the midst of a massive push to extract more oil and gas from the nation’s waters and wide-open spaces, the Trump administration has set its sights on a new goal: to ramp up drilling in national forests.

In September, the U.S. Forest Service “updating, clarifying, and streamlining” regulations that could broadly change how the agency handles oil and gas leasing across the 193 million acres of national forests and grasslands. “The intent of these potential changes would be to decrease permitting times by removing regulatory burdens that unnecessarily encumber energy production,” the Forest Service wrote. “These potential changes would promote domestic oil and gas production by allowing industry to begin production more quickly.”

Environmental groups are outraged. “What they want to do is clear and pave the way for faster permits for the oil and gas industry,” says Kristin Davis, staff attorney with the . That means ignoring the public and its concerns, says Davis’s colleague Sam Evans, senior attorney and leader of the group’s National Forests and Parks Program.

National forests are the “land of many uses,” as the old slogan goes. They are habitat, a place for recreation, and for 180 million Americans. The Forest Service has a mandate to balance these uses wisely—not favor industry, critics say.

Oil and gas in national forests are in an interesting way. The Forest Service, which is part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, oversees most federal forestland and what happens there. Yet the Bureau of Land Management, which is part of the Department of the Interior, administers the oil and gas deposits and hard-rock minerals beneath the forests. Each agency has its own expertise and its own responsibilities. Current rules spell out a complementary regulatory pas de deux, with each agency playing a part in deciding which forestlands may be appropriate for drilling or mining and how the activities ultimately occur.

Energy companies and environmentalists agree the process can be improved. But that’s where the agreement ends. The Forest Service’s September 13 proposal in the Federal Register portrays a cumbersome system that slows energy development. Its brief proposal makes more than a half-dozen references to aiding industry, through “quicker lease decisions” and “decrease[d] permitting times.” Environmental groups counter that the permitting process needs to be bolstered, not streamlined, with environmental review occurring at smarter stages during the process. Red tape and other hurdles aren’t the hang-up in the system, they argue, but instead it’s problems such as staffing: In 1995, were 16 percent of the Forest Service’s appropriated budget. In 2015, firefighting consumed half of the agency’s budget, with a 39 percent reduction in all non-fire personnel.

Critics are particularly worried by the proposal’s stated desire to “[align] the Forest Service process with the BLM so that operators have one simplified permitting system.” But the two agencies aren’t supposed to be aligned, attorney Davis says. Each has a distinct, crucial role to play, she says. “It’s complementary work, but it’s not duplicative.” When the government aligns the two processes, “What you are doing is gutting the environmental review process,” Davis continues. “If you’re going to scrap that and just do what BLM does, you’re getting rid of where the real work happens.” Such a change would eviscerate the Forest Service’s ability to control what happens on the land it is supposed to manage, she and other critics charge.

Aligning the processes also would remove the public from the process, attorney Evans argues. He and others point to the BLM’s aggressive moves to expedite energy development on lands the agency manages—by increasing the rate of lease sales and by reducing environmental review and curtailing public input.

The Forest Service downplayed such concerns. The law requires “timely and coordinated action on leasing applications and expeditious compliance with environmental and cultural resource laws. This is the alignment we seek,” a Forest Service spokesperson wrote to �����ԹϺ���. “Each agency has its own roles and responsibilities. These are set out by Congress in the statutes and cannot be changed by regulation.”

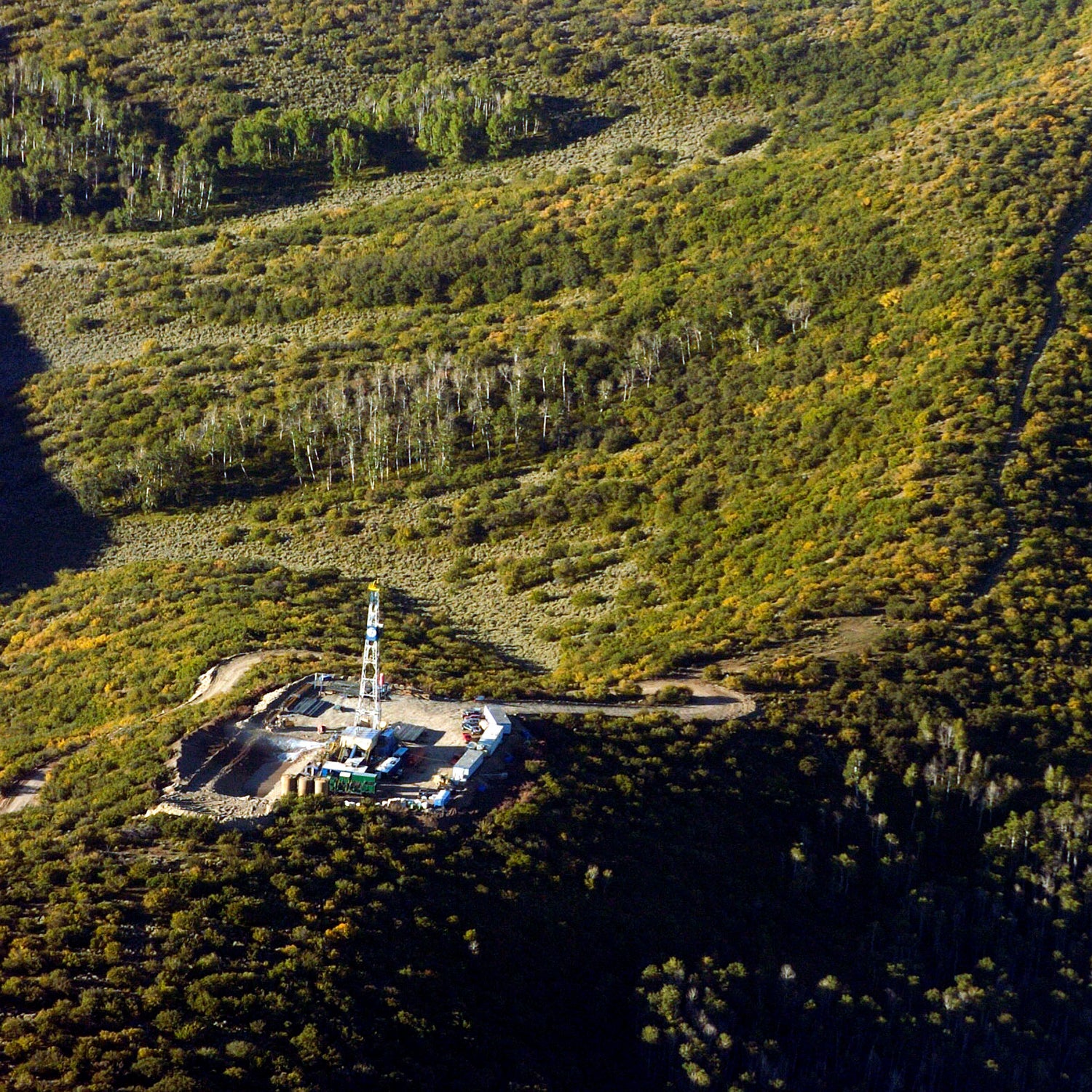

The Forest Service oversees 154 national forests, 20 grasslands, and one prairie; 44 of those properties have oil and gas interests or operations. The Forest Service has also proposed changes to the permitting process for mining operations in national forests.

The oil and gas proposal is a little-noticed front in the Trump administration’s broader goal to expand domestic energy production where possible, from expanding offshore drilling to rolling back methane rules and other environmental protections.

Notable in the proposal, says Nada Culver, senior counsel for the , “There’s not a single reference to what the risks associated with this [drilling] activity will be, not to mention accelerating it.” Last month, Culver co-authored a letter to the Forest Service, signed by four dozen regional and national environmental groups, protesting the proposed changes. The letter expressed frustration that the public was given only 30 days to comment on the proposed changes.

The Forest Service will draft new regulations and publish them for public review and comment sometime next year.