I’ve spent two minutes in the Boy Scouts office in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and it’s clear they’ve forgotten us. “I’m looking for anything related to the Girl Rangers,” I ask the woman behind the desk. “We were the first all-female Boy Scout troop in the nation.”

I’m here to find physical evidence to prove that we—a rogue, high-adventure Boy Scouts of America Explorer troop of teenage girls in the 1970s—existed. As a group, we hiked the Appalachian Trail, paddled more than 1,000 miles of rivers in the Carolinas, and climbed some of the highest peaks in the Smokies on horseback. My quest was spurred by the from the BSA that it would begin accepting girls as Cub and Eagle scouts for the first time in its 107-year history. The media trumpeted that the gender barrier was falling, but I knew the Girl Rangers brought it down more than 48 years ago.

I’m on the trail of one thing in particular: the journal entries I wrote as the Girl Rangers’ scribe about our monthly backcountry trips. I was 14 years old when I joined the troop; I’m now 59. I vaguely remember creating these reports on my baby-blue typewriter—two or three singled-spaced pages for each expedition, which I’d read at monthly troop meetings. If I could find these reports, I could recover the memories that had faded in the intervening four decades.

I remember one of our mottos: A Girl Ranger never gives up. After coming up empty at the Spartanburg offices, I email the national Boy Scouts office. They have no records, either. I go to the church that hosted our troop in Spartanburg. Nothing. Then I head to the local library, where I find a trove of newspaper articles on microfiche that help our story begin to emerge.

In October 1970, four junior high school girls showed up on the front porch of the man in charge of the Spartanburg Boy Scouts Explorer group, known as Post 1. George Withers, then 54, was a slight man, gaunt and wiry like a coyote, with long brown hair combed to the back of his head. The girls were armed with news that the national BSA office had decreed that women ages 14 to 18 who were members of the Girl Scouts or Campfire Girls could now attend meetings and outings of the Explorers, a branch of the Boy Scouts intended for teenagers that, in most posts, emphasized teaching outdoor skills. Withers told the girls that his boys’ Explorer troop was full. But “[w]hen I saw those fallen faces, I knew I had to do something,” he told a local reporter six weeks later. “So I suggested: Why not form a girls’ group with the same program as the Explorers and call it Girl Rangers?” It would be the first of its kind, identical to the BSA Explorers, with an emphasis on learning outdoor skills, such as horseback riding and canoeing.

Seventeen girls showed up for the first meeting, and 28 the next. By the fourth week, Withers capped the membership at 55. The girls chose navy blue warm-up suits as their uniforms and created their own triangular scout patch with the words “God, Country, Family, Girl Ranger” emblazoned on it. They adopted the same bylaws as the boy Explorers, except they cut the line “Excessive length of hair—30-day suspension.” For months, the Girl Rangers operated as a kind of shadow Explorer troop, neither Boy Scouts nor Girl Scouts. Then, in April 1971, the national BSA Explorers officially went coed. The South Carolina Girl Rangers registered as an official Explorer post and became the first all-female troop in the nation. There were still caveats—they couldn’t become Eagle Scouts, which meant there were dozens of BSA merit badges they couldn’t officially earn. But it was a start.

“There was a sense that we were proving something, that we had a responsibility,” says former Girl Ranger Lucy Lyles Henner. “Learning how to be physically competent and strong carried over to a feeling that I could be competent and strong anywhere.”

A year later, at age 14, I signed up.

I had been a Girl Scout dropout. I clearly remember why. When I was eight, the Girl Scout troop leader had asked us to sew a “sit-upon”—a decorated plastic placemat that you wore on your butt to keep it from getting dirty when you sat down. I thought, If they are telling me not to sit on the ground, what else will they tell me not to do?

A friend from junior high told me I was tough enough to be a Girl Ranger and invited me to a troop meeting in the parish hall of the downtown Episcopal church. I was an immediate convert. These girls—who laughed and joked about their challenging adventures in the mountains and on the rivers—were my people. They handed me the Girl Ranger patch and sent me off to Crutchfield’s Sporting Goods to get my own blue warm-up suit.

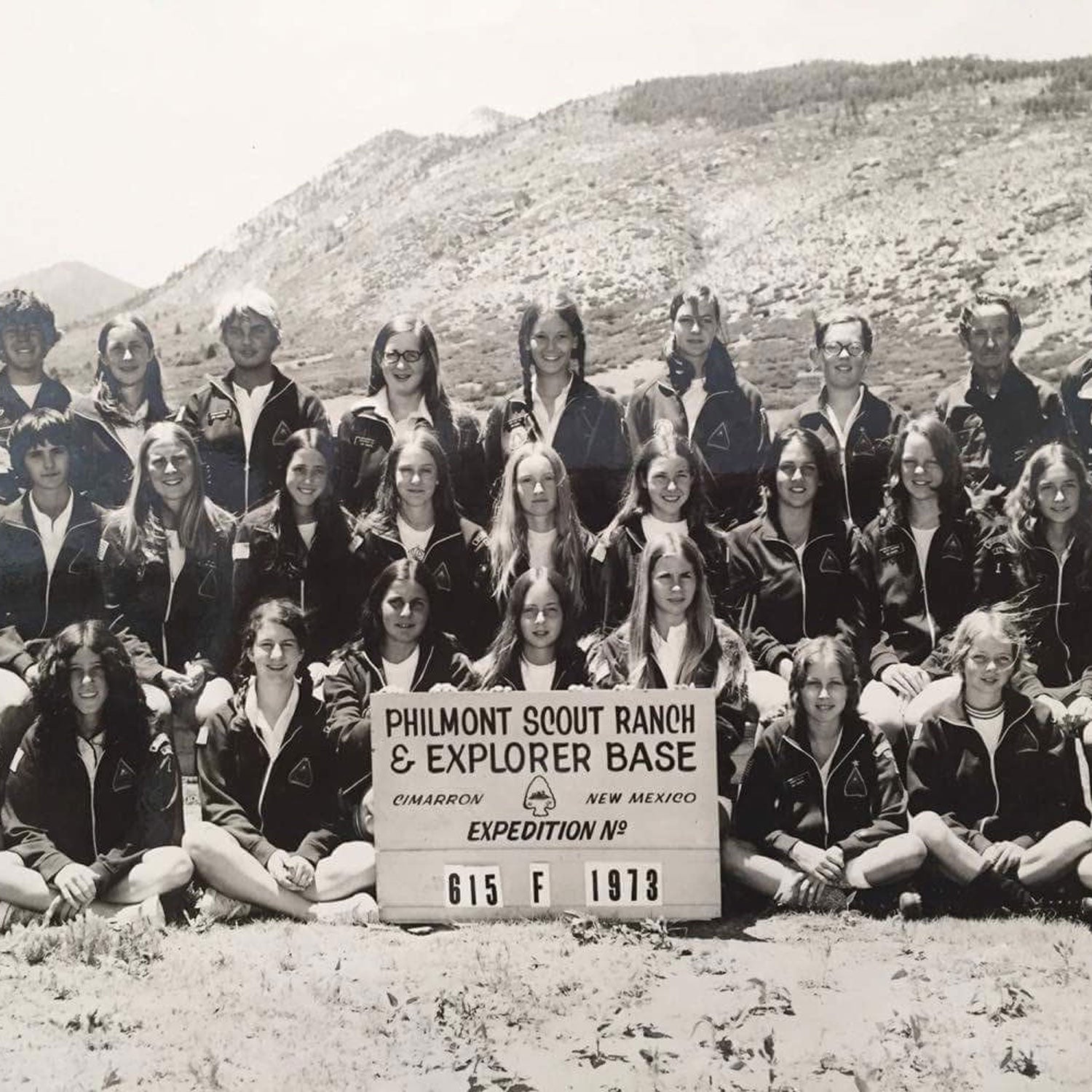

For me, the moments that stand out most are the bus rides into the Smoky Mountains. We’d leave Spartanburg before dawn, our packs stuffed with sleeping bags, tents, and freeze-dried food. Usually about 40 of us would rumble up the highway. I was so small that I could climb up into the luggage rack and lean over the edge to talk to other girls, who ranged in age from 13 to 18, and came from schools all over the area. In June 1973, one of those buses took us all the way to Cimarron, New Mexico, where we were the first all-female expedition among thousands of boys at Philmont Scout Ranch, hiking peaks above 10,000 feet.

About that time, girls all over the country flooded into the BSA Explorers. By the early 1990s, girls made up about half the membership, with troops focusing on science and engineering, fire and rescue, law and more. The Explorer program ended in 1998, splitting into career-oriented posts and outdoor-oriented posts, which remain coed to this day.

A few days after reading the newspaper clippings, former Girl Rangers—many of whom I’d lost touch with years ago—started crossing my path again. I ran into Susan Fretwell, now an attorney and one of the original Girl Rangers, at a party in Spartanburg. I didn’t know her well, but I told her I’d seen her photo in the newspaper from 1970. “We were trailblazers!” Fretwell said. “And nobody remembers us.” A few days later, she invited me to her office and pulled out her blue Girl Ranger jacket from the closet. There on the back were two Boy Scout merit badges: one for hiking, one for camping.

Then I called my old friend Ann Altman, a Presbyterian minister in Missouri who, like me, is turning 60 this year. The first thing she told me is that she was looking at a line of Girl Ranger trophies on her mantle: (three of them), #1 Horseman Class B, #3 Hiker and Camper. “It gave me a lot of confidence and courage,” Altman says. “It also gave me a lot of cool stories to tell.”

An hour or so into the conversation, I realized why I was so fixated on the scribe reports. I became a writer during my three years in the Girl Rangers. As I grew up, I went on to work at five newspapers, then founded a Southern publishing company and opened an independent bookstore. Today I edit books and do some freelance writing. I also fell in love with the outdoors during my days as a Girl Ranger. Since then, I’ve rafted the Reventazon River in the Costa Rican rainforest; walked the windy, coastal clifftops of Pembrokeshire, Wales; kayaked travertine waterfalls in Mexico; and hiked the rocky Tablelands in Newfoundland’s Gros Morne National Park.

“It affected my life in an amazing way,” says Missy Johnston Smith, now a schoolteacher in Charlotte, North Carolina. “I wasn’t a girly girl. Rangers gave me an outlet for who I really was. We didn’t yell about how great we were—we just went out there and did it. It made me tougher and more determined, which are not bad traits to have.”

The media is trumpeting that the gender barrier is falling, but didn’t the Girl Rangers bring it down more than 48 years ago?

About the time I was ready to give up my search for the reports, my phone rang. It was Leslie Withers, the 72-year-old daughter of George Withers. I’d come across her name in George’s 1991 obituary, found her number, and left her a long voicemail explaining my quest. She called back to tell me she had uncovered a 25-year-old box in her attic. She had tried to send it to the Boy Scouts decades ago, but it came back—bad address.

Two days later, the box sat atop my kitchen counter like some kind of Girl Ranger Holy Grail. I pulled back the bubble wrap to reveal three colorful scrapbooks. I flipped through brittle, yellowed pages to find other girls’ typed reports of hiking and paddling expeditions. These were the scrapbooks covering the four years after I was scribe (though I was still part of the troop), but as I kept turning pages, that ceased to matter. Here were a slew of photographs, faded now almost to pastel. Here was the handwriting of dozens of girls who wrote comments about each trip during the bus rides home.

“This trip was a study in frustration for me,” writes Lisa Shingler in June 1974 after we didn’t reach our final destination on a five-day hike on the Appalachian Trail in North Georgia. Withers apparently hadn’t planned for such steep terrain. “We can’t make the whole 70 miles, the chicken chop suey didn’t cook, the sparklers didn’t light and I lost my flashlight!”

“Boy, I tell you there sure are some lazy Rangers around here!” writes Charlotte Fleck after a two-day horseback trip in July 1974 up Mount LeConte, a 6,593-foot peak in the Smokies. “Where were all of you bums while we were up on that mountain coaxing our horses through 9 inches of mud?”

I saw the flourish of my teenage signature as I mocked myself for regular clumsiness on the trail (“I only fell down once and cut myself twice. I hope I don’t lose my image!”). Another time I joked that I caught three skunks in the campsite. I read the stories of meeting strangers on the trail who refused to believe that we were Boy Scouts. I saw the names of so many girls who have disappeared from my life. These riches belong to them.