You don’t have much time to grab people’s attention nowadays. This is one of the things I emphasize in my annual writing workshops, before we read through a handful of first sentences that do just that—grab our attention, make us sit up, engage, and dive into the rest of the story. One of them, which I have memorized: “We are waiting in the desert to kill our dog.” (That’s Terry Tempest Williams, in .)

Writing stories for modern readers is tough—we all have overflowing inboxes, or we’re on phones or computers where something less boring is literally two taps or clicks away, and a story almost always has to grab you from the start, or at least make you curious enough to stick with it. I wish it wasn’t like this, and we had more options, but if we’re writing online, that’s the way it is.

With a book, a story has a little more time to get the reader’s interest, and convince us that the story in your book is worth buying, or at least borrowing. Maybe we’re standing in a bookstore, reading the first paragraph or first page, or maybe we’ve downloaded a sample of the ebook. If we haven’t already heard about a book through a friend or a bestseller list or a famous podcast, the first few pages are what pulls us into a story, and helps us decide if we want to spend several hours of our lives reading the book. When it’s good, I find myself clapping the book shut and walking to the bookstore cashier or library checkout, excited to finish washing the dishes after dinner that night and start reading.

As far as adventure books go, there is one opening scene I have been talking about for more than a decade, because it’s unforgettable, and because it does a fantastic job of getting the reader into the story immediately, within four pages.

The book I’m talking about, interestingly, wasn’t written with a 2024 audience in mind—it was published in 1983. So why do I think it’s so great? I’ll break it down here. (I’m not going to copy and paste the entire first four pages here, but they’re viewable if you’d like to read them, or as a sample on Amazon.)

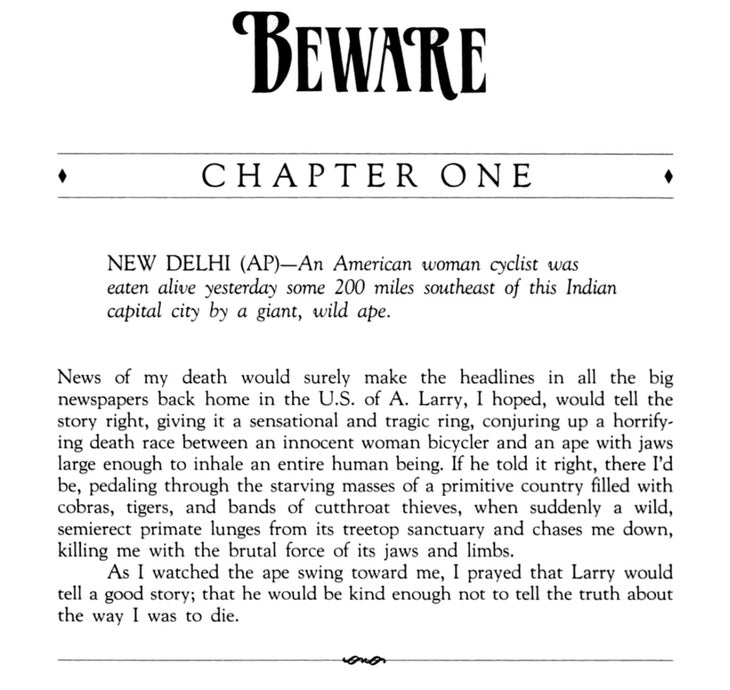

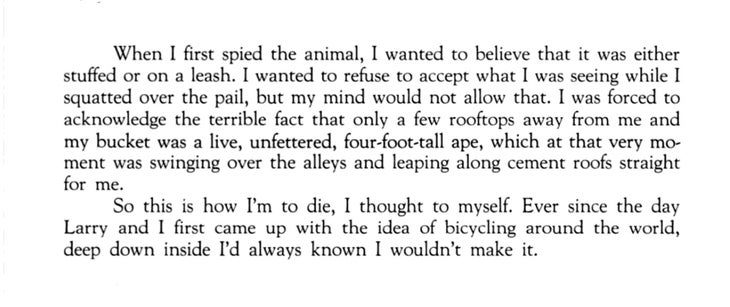

Here’s the first page:

One of Kurt Vonnegut’s eight famous rules of how to write a good short story is: “”

Vonnegut was talking about fiction, but his point, I think, can be applied to adventure writing in that we don’t necessarily want to start at the beginning of the story. Does Barbara Savage start with a scene where she and her husband, Larry, are packing for their two-year around-the-world bicycle trip? Or when they first started dreaming up the trip? No, she starts the book with a scene where she’s about to be mauled by a wild ape, sure she’s about to die. (More on that later)

Also, she gives us some intrigue with that last line: “… I prayed that Larry would tell a good story; that he would be kind enough not to tell the truth about the way I was to die.”

Wait, so what is the truth? Of course we read on.

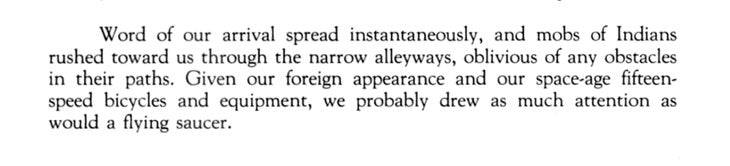

Savage goes on to explain the actual who, what, when, where, and why: It was November 1979, and she and her husband, Larry, were bicycling through India toward Nepal with a new friend, Geoff, who they’d met after arriving in India. She had suggested they pedal the back roads out of New Delhi, to see the countryside and avoid truck traffic. After five days of riding, they’d made it to Mainpuri, at that time a city of about 1 million inhabitants, where “no one in the shops spoke English, and the people in the town stared at us more in disbelief than curiosity.”

An English-speaking doctor directed them to a boarding house, and when they found it, Larry went inside to arrange for rooms while Barbara and Geoff waited outside with the bikes. At that time in that part of India, touring cyclists were an uncommon sight, and their appearance anywhere drew stares, and crowds. In Mainpuri, she wrote, they were immediately surrounded by curious residents:

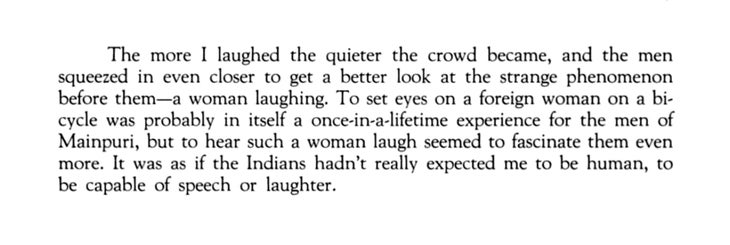

Chaos continues as the mob of people builds; a rickshaw is overturned, people are trapped underneath, they became claustrophobic, and then Geoff, who hadn’t quite recovered from dysentery he picked up in Iran or Pakistan, tells Barbara he’s about to poop his pants—which is not funny when it’s happening to you, but can be funny when you’re reading about it happening to someone else. And also funny if you’re Barbara Savage, standing next to Geoff, because she started laughing—which quieted the crowd:

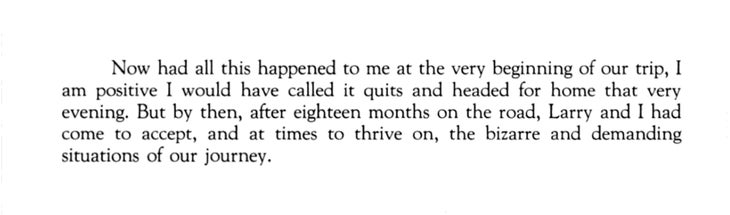

They get into the boarding house, and once in their room, Barbara needs to use the toilet. Except the only toilet is a bucket up on the roof. She makes her way to the rooftop, where she squats over the half-full, reeking bucket to relieve herself. And then she sees the ape:

She sprints to the stairs and manages to get downstairs into their room before the ape reaches her, and survives. But of course, we know she survives—she wrote a book about the trip. In the final paragraph, Savage brings us up to speed:

So that’s chapter one, or the beginning. Do I want to read about more of those bizarre and demanding situations from their two-year, 25-country, 23,000-mile bicycle adventure, in the late 1970s? Well, for one, I like this narrator—for several reasons:

- She has obviously seen some stuff and has the grit to survive tens of thousands of miles of human-powered adventure;

- she knows how to tell a story with humility;

- she seems more concerned with telling a good story than impressing the reader, and

- she is able to laugh when things get crazy.

The other reason I love this opening scene is because I can summarize it in about 15 seconds when I’m talking to someone about the book: She’s bicycling across India, using a bucket toilet on a rooftop, and a wild ape is bombing across neighboring rooftops straight for her, and she’s sure she’s going to die, getting mauled to death by a wild animal while using the bathroom.

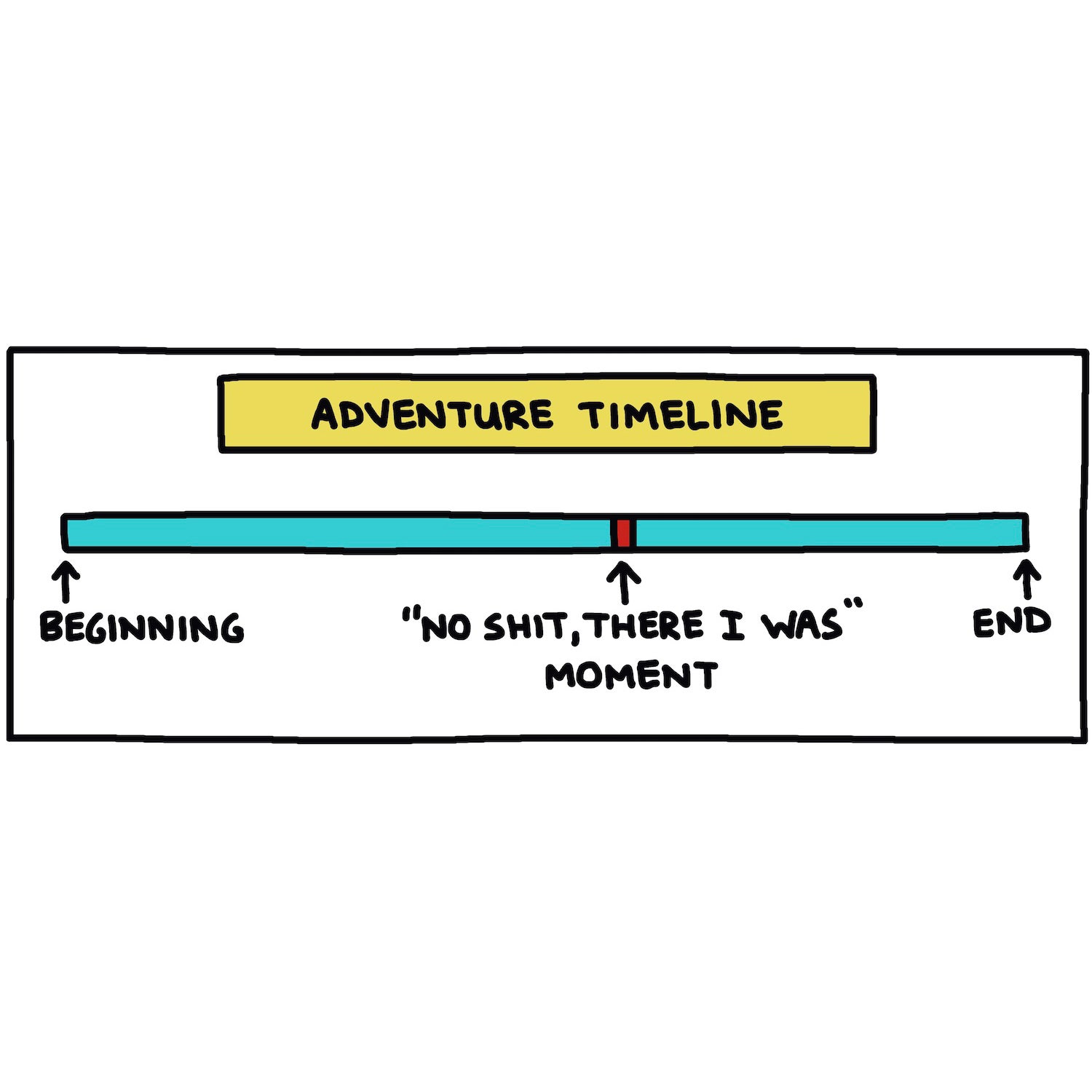

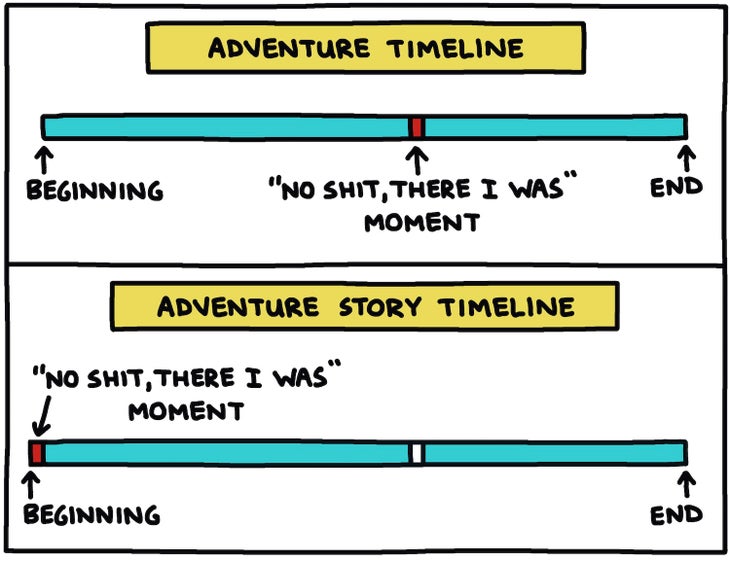

Barbara Savage masterfully illustrates a technique I try to impress upon workshop students about writing adventure stories: You should try to start your story with the “No shit, there I was” moment.

This is not the only way to begin an adventure story, but it usually works to get me reading further. A couple examples from other books:

“I saw the avalanche coming. It charged over the step of dirty brown ice above like a breaking wave of black water. It hammered back down into the gulley, driving into us like the fist of God, and I screamed.” —Barry Blanchard, The Calling: A Life Rocked by Mountains

“I’m standing on the bank of the swift Chandalar River in the Brooks Range of northern Alaska, trying to gather the courage to swim across. My husband, Pat, is by my side. We’re alone, as we have been for most of the past five months.” —Caroline Van Hemert, The Sun is a Compass

“The order to abandon ship was given at 5 P.M. For most of the men, however, no order was needed because by then everybody knew that the ship was done and that it was time to give up trying to save her. There was no show of fear or even apprehension. They had fought unceasingly for three days and had lost. They accepted their defeat almost apathetically. They were simply too tired to care.” —Alfred Lansing, Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage

Tragically, Barbara Savage died in a cycling accident just before Miles from Nowhere was published in 1983. Her husband, Larry, donates the proceeds from the sale of the book to the in cooperation with Mountaineers Books, to encourage and enable adventure writing in the spirit of the book.