The Top 10 Films at Sundance

I hit up the last month to scope out ten of the most affecting adventure and environmental films, and found flicks that had the rare power to depress and inspire me at the same time. Chasing Ice, a documentary about James Balog’s climate change project, is 75 minutes of stunning cinematography—but it’s also a eulogy for the world’s disappearing glaciers. The Ambassador is an absorbing documentary about journalist Mads Brugger’s gutsy journey into the heart of the blood diamond business—but it’s also a sobering expose on a deeply corrupt industry. Then there’s the provocative yet infuriating Atomic States of America, which examines the history of nuclear energy, and the visually spectacular yet haunting Beasts of the Southern Wild, a fictional account of how climate change might play out in southern Louisiana. We also included a few films that you might not expect, including Detropia—a film about Detroit that speaks to the need to reassess our cities. Check out our coverage for all ten films, some of which will be coming to theaters and cable networks in the next year.

A Fierce Green Fire

A new documentary by Mark Kitchell tracks the history of environmental activism

Pick an environmental documentary at random and chances are it tackles some hot-button issue. is a gentler breed of environmental doc, in which director plays earnest chronicler of a movement that we’ve all come to take for granted.

Kitchell tracks the history of environmental activism by spotlighting five milestones: 1) the ’s crusade to keep the Grand Canyon free of dams, 2) the , where residents protested Hooker Chemical for dumping 20,000 tons of toxic waste in their backyard, 3) the creation of , 4) the to preserve the Amazon rain forest, and 5) ’s campaign for climate change education. The film is plodding at times, but what ultimately emerges is a retrospective of the movers and shakers who’ve paved the way for environmental activists of the future—and their collective conviction is inspiring.

The most illuminating insight arrives by way of Kitchell, who notes that the environmental renaissance began, in part, when humans observed the first images of Earth from space. That moment, Kitchell says, forever altered our perspectives of our role on the planet. It’s a stirring notion to keep in mind the next time you find yourself gazing at a photo of the big blue dot.

Detropia By the Numbers

Two filmmakers capture stories of survival in a decaying Detroit

Detropia

A scene from Detropia

A scene from DetropiaThe media fetishizes the Motor City’s decline with pictures of abandoned factories, dilapidated storefronts, and homes ablaze. It’s a creation that has led international tourists to stop in the city. In , which premiered at the over the weekend, directors and capture the urban decline without turning it into decay porn. Graffiti and overgrown lots abound, but the focus is on the citizens as they cope with the very-real consequences of a city in financial turmoil. For example, how will they respond to the mayor’s request to move into a centralized area? Here’s a look at the city as profiled in the movie, by the numbers.

1.86 million The population of Detroit in 1955.

713,000 The population in 2010—the lowest total in 130 years.

150,000,000 The amount of Detroit’s budget deficit.

10,000 The number of homes that have been demolished in the past four years.

50 The percentage of manufacturing jobs lost in the Motor City in the past decade.

40 The number of square miles that are inhabited in Detroit, filling less than one-third of the city’s 139 square miles.

25,000 The price for a loft apartment.

Two Number of Swiss tourists in the film who travel to the city to witness the decay.

The Atomic States of America

Directors Don Argott and Sheena Joyce trace the evolution of nuclear energy

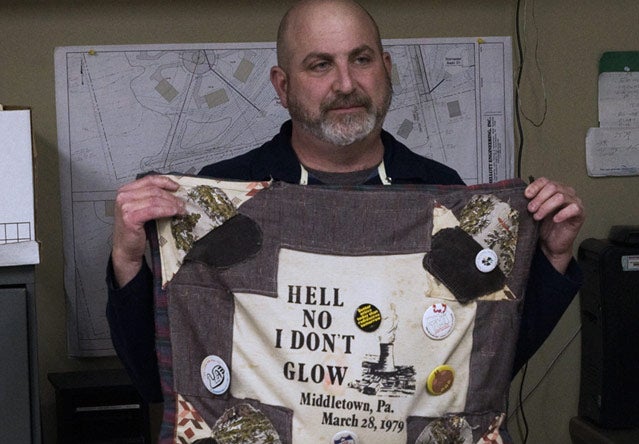

In the wake of the Fukushima disaster in Japan, casts a timely inquiry into the viability of nuclear energy, a technology with enticing advantages but horrific fallout consequences.

Directors Don Argott and Sheena Joyce trace the modern nuclear renaissance to the “peaceful atom” campaign, launched by the U.S. government soon after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ads and PSAs touted nuclear energy as a constructive technology—the way of the future—as Americans welcomed facilities into their backyards. An energy source that emits no greenhouse gases, infuses local economies with jobs and decreases dependence on foreign oil? Hell, yes.

Joyce and Argott carefully consider the flip side as they visit communities that have been rocked by nuclear leakage and hit with inordinately high rates of cancer. They point to a series of cover-ups at nuclear facilities where evidence of leakage and meltdowns have been found. They question whether the United States imposes strong enough safety standards on facilities such as in Buchanan, New York, which lies on two fault lines.

The testimony from victims is emotionally compelling, but Atomic States is ultimately driven by evidence—enough, surely, to urge nuclear proponents to consider whether the potential consequences outweigh the benefits. Or as one activist explains, “We haven’t reached the point where humans can responsibly split atoms.”

Lost On Vacation

Filmmaker Kieran Darcy-Smith talks about his new international travel thriller, Wish You Were Here, which premieres at Sundance 2012

Kieran Darcy-Smith filming in Cambodia

Director Kieran Darcy-Smith filming in Cambodia

Director Kieran Darcy-Smith filming in CambodiaActor Joel Edgerton

Actor Joel Edgerton

Actor Joel EdgertonIn , the new psychological thriller from director , two couples from Australia go on vacation in Cambodia and return home with one less person. Secrets emerge as they try to figure out what happened. We spoke to Darcy-Smith about his grueling two-week film shoot in Cambodia.

The movie starts off almost as an ad for Cambodian tourism, showing off the beaches and the nightlife. But then it spirals into a traveler’s worst nightmare. Did the Cambodian government ever express concern about how the country would be portrayed?

That’s a really good question. I don’t think they ever read the script. I think they were more interested in how much we were gonna pay and whether or not we were gonna sign the documents and how official we were gonna make things. I don’t know. I’m a little concerned, I guess, how it might be perceived by some people, because it’s not a negative slight on the country or people at all. Again, trying not to give anything away, but there’s underground or underworld elements to every society. There’s a small underbelly of that particular country, but you find the same in Sydney. There’s movies shot in Sydney that show the same thing. I just hope there’s no sensitivity around it. I think people will get that it exists in every society.

What were some of the challenges unique to shooting in Cambodia?

I had a five-and-a-half-month-old girl and a two-and-a-half-year-old boy and my wife was in the lead role, so that was pretty challenging. Plus Felicity [Price, his wife] and I were really ill. I fell into a sewer up to my neck on day one, and then I got really, really ill. I had really bad dysentery, and a really bad flu. We were shooting 15-hour days.

So you have dysentery and the flu, but you’re on a tight shooting schedule. Did you take days off?

Oh no, no, but it’s funny, the adrenaline kicks in and you just do it. I was having the time of my life. It’s such a challenge. They don’t really have a big industry there, so the gear, with all due respect, was second-rate. We had a lot of issues with lights and technology. The crew we were working with, they didn’t speak English at all, so we had interpreters working for us and you get these lost in translation moments, so it slows things right down. Everything about it was difficult, but we certainly got what we wanted.

You shot part of the movie in Sihanoukville. Can you describe what it was like to film there?

It’s beautiful, and it’s crazy, too. I can’t give anything away, but all that stuff towards the end of the movie is shot in the real deal. At the back of the port is a brothel area and it’s all run by gangsters. It’s arguably one of the most dangerous parts of the country, but it’s a magnificent country. The first time I went there was 1996, when the war was still on. You couldn’t get anywhere because the was everywhere.

When you shot in Sihanoukville’s seedier streets, how did you go about clearing the area for a movie shoot?

The fixers did. It’s all really about money. As long as you sort of connect with the right people and pay the right amount of money, you’ll be safe and looked after. And we were really well-looked after. Everyone was on our side. We were working in an area that was sort of gangster-run, but they weren’t gonna let anything happen to us. I hope I’m not saying anything out of school. I just love everything about the people.

How did you go about picking locations?

We did an initial location scout, where we went to Vietnam and cast our actors, or some of them. Then we went to Cambodia and cast the Cambodian crew. Then we just went out for two weeks to all these different regions with a really great company that facilitated and all these other big movies [that were shot in Cambodia]. So they knew the lay of the land. Actually, one of the guys who writes for , he’s the Lonely Planet Cambodia dude, he was really helpful in connecting us. So we spent a couple weeks cruising the country. I had very specific locations in mind because I’d been there.

Did you run into any issues with shooting in locations that still have land mines?

No, not where we were. You’ve really gotta head to the border regions now. They’re doing a lot of great work with clearing the mines. In ’96 it was a different story. They’re still doing it. There are teams out there every day.

The House I Live In

Eugene Jarecki discusses his new film about the government’s war on drugs, which won the Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Documentaries

Movie screenshot

Screenshot from the movie The House I Live In.

Screenshot from the movie The House I Live In.In the past decade, Eugene Jarecki has directed documentaries on Henry Kissinger (), Ronald Reagan () and the military-industrial complex (). At this year’s Sundance Film Festival, he premiered his latest film, , an in-depth examination of the nation’s war on drugs. Jarecki traces the roots of the war to Richard Nixon’s famous declaration in 1971, and then illustrates how the battle has become an ineffective enterprise and an unexamined method of suppressing the poor. Jarecki sat down with �����ԹϺ��� to discuss the film, which .

Why did you want to make this film?

There are people I knew, in particular African-Americans, who were suffering from what seemed a surprising kind of aftershock of the Civil Rights movement. There was one family I was particularly close to, the matriarch was Nannie Jeter. They, and I, all thought we were all on a post-Civil Rights path where we would kind of share in the same American promise. Instead, as I met privilege and possibilities, they met a lot of struggle. Over time this has stayed with me a lot. It’s been a theme in my life: What happened to the Jeter family? When I asked Nannie what she thought went wrong, she said she thought it was drugs, that the primary enemy that had attacked her loved ones was drugs. And then of course I wondered why had that happened to them and not my family, and why did it seem to be happening to a lot of African-American families? That led me to ask further questions of experts in the field of addiction, and also society and law. What’s going on here? They all looked at me like the inquiry about drugs was only half the story. Drugs were a problem for people, but as David Simon says in the film, whatever drugs hadn’t destroyed, the war against them has.

How hard was it to find critics of the war on drugs?

As I started to go around the country, I couldn’t find anyone who would defend this war. It has cost over a trillion dollars, there have been over 44 million arrests. It has made us the world’s largest jailer—2.3 million people in prison. That’s more in absolute numbers than any country in the world, including totalitarian countries. We incarcerate a far higher percentage of our own people—not just in absolute but in relative numbers—than any other country, including China. China has about 2.3 million people in jail but they have a population of about 1.5 billion people. We have 2.3 million of just 280 million, so about 1 percent of our population is in jail. This is China, which Americans sort of single out as the country of disregard for human dignity. So that’s startling. You look at all those figures, you can’t get anyone in their right mind to defend a system that has failed in every way to reduce demand, reduce supply. More Americans use drugs than before, so it’s failing on every level and costing a fortune.

You bring up the fact that Nixon initially approached the war on drugs by spending lots of money on treatment, not law enforcement.

Despite his war-like rhetoric, behind the scenes he was spending two-thirds of his money on treatment, not on law enforcement. So he knew, and yet he was willing to play the political game of using tough-on-crime rhetoric to get elected. His success in doing that formed a mold that politicians have followed ever since.

At one point you ask what originally made drugs such a perceived danger, and you trace it back to the illegalization of opium as a way to criminalize the Chinese in the 1800s.

I learned that from [historian] , who was in the film. What we did with the Chinese with opium was so very similar to what we did with crack cocaine. Because in America in the 1860s—the analogy is amazing—the number one user of opium was a middle-aged white woman. In this country, the number one user of crack is a white person. And yet the white woman didn’t go to jail and the white people don’t go to jail today. Instead we put the Chinese away, and we put the Chinese away in a very similar way to the way we put black Americans away. The Chinese got put away because we made one way of taking opium illegal. In the contemporary context, we did the same thing with crack. Crack is a form of cocaine and is actually the same chemically as cocaine—you’re just taking it in a different way because it’s cooked with baking soda and water. They made opium illegal but not all opium. They only made smoking opium illegal because that was what’s called the delivery mechanism that the Chinese used. So both with crack and opium, the laws that have been passed were laws passed against a particular delivery mechanism. The drug itself is of varying legality and illegality determined quite arbitrarily by those in power, and I find that parallel very haunting.

You make the point that many of the drug users and dealers, who tend to get the blame in the war on drugs, are actually acting rationally within a system that is irrational.

How many American wars can we describe that really are rational? And the drug war is simply our longest war, which represents our greatest and longest departure from reason. To have thought you could declare war on a chemical or series of chemicals and not know implicitly that you’re really declaring war on the users of those chemicals, now you have war against a large section of your own people.

Do you think “war on drugs” should be banned as a slogan?

The Obama administration has abandoned it. The director of , who’s also known as the drug czar, doesn’t call himself a drug czar and doesn’t call it a war on drugs. That’s commendable, but it’s kind of window dressing if the policies stay the same. And the Obama administration has not paired its abandonment of the term war on drugs with meaningful policy reform.

You shot this film in more than 20 states. Is that the most legwork you’ve put into producing a movie?

In terms of geography, I’ve never traveled as far and wide. I didn’t wanna leave any stone unturned. I didn’t want someone to watch the movie and say, you know, that’s true on the east coast, but it’s really different down here in Oklahoma. Or that’s true in Oklahoma, but in California we do things really differently. So I wanted to make sure that I had enough places that if you heard a cop in Providence share his reservation about the war on drugs, you could go down to New Mexico and find a cop there saying the same thing, and in Seattle. What you find is a tremendous amount of overlap. You get a judge in Sioux City, Iowa, saying precisely the same things that a perp sitting in a Vermont jail told me. They agree about the unfairness of the law. The judge feels bad that he’s giving a sentence that he doesn’t agree with because his hands are tied by what are called mandatory minimum sentences, and the perp is sitting there about to spend a tremendous amount of his life behind bars because of mandatory minimum sentencing laws.

What are some of the reactions you’ve had to the film so far?

I think people are shocked. People feel overwhelmed by the enormity of the human cost that’s involved, and they wonder what they can do about it. The next time a politician comes around and says vote for me because I’m gonna put away all the bad guys, they’re gonna be able to say that person is simply pandering to me for my vote.

Bear 71

A new interactive movie documents the journey of a grizzly bear in Banff National Park

Bear 71, an interactive online documentary that premiered at the , opens with an ominous epigraph: “There aren’t a lot of ways for a grizzly bear to die. At least, that’s the way it was in the wild.” A second later, you’re watching close-up footage of a 3-year-old grizzly trapped in a snare at . As we learn from the female voiceover, told from the bear’s perspective, the snare snapped shut with the “breaking strength of two tons.” But she’s not dead. Instead, park rangers tranquilize her with a shot of Telazol, tag her with a VHF collar, and release her back into the wild—christened as Bear 71.

For the next 20 minutes, the poetic narration paints a portrait of Bear 71’s life over the course of a decade. The bruising narrative informs you that, for example, trains have in the last decade (bears roam the tracks in search of grain leaked from trains). Or that “bears and humans here live closer together than any other place on earth.” Or that there are 44 ways for animals to cross Banff’s highways—even though, as Bear 71 wryly points out, “There’s nothing natural about a grizzly bear using an overpass.”

Short grizzly videos accompany the narration, and when the videos aren’t playing, you can use your mouse to navigate over an interactive map of Banff. As your pointer glides across the terrain, you encounter wolverines, moose, wildcats, and other fauna—each represented by a thumbnail that enlarges into a video. Co-creators and collated the footage from a collection of one million images shot by motion-sensor cameras around the park.

There’s a technology theme at play here, but the more gutting message of Bear 71 is the way in which human presence—roads, trains, tourists—has affected Banff’s natural habitat. (It’s all heightened by a powerful soundtrack that includes , and .) Essentially, animals are being punished for acting naturally in an increasingly unnatural environment. In Bear 71’s words, as she frets about the future of her cubs, “They’ll have to learn not to do what comes naturally. And I wonder, maybe the lesson is too hard.”

To watch the full movie and interact with Bear 71, go to .

Skateboarding Canon

Stacy Peralta talks about his new documentary Bones Brigade: An Autobiography, which premiered at Sundance 2012

Stacy Peralta Filming

Back in the day

Back in the dayStacy Peralta

Stacy Peralta

Stacy PeraltaIN , Stacy Peralta returns to his skateboarding roots to chronicle the young skate team he created in the 1980s. Combining archival footage and present-day interviews, tells the stories of the teens he groomed into skating legends: Tony Hawk, Steve Caballero, Rodney Mullen, Lance Mountain, Tommy Guerrero and Mike McGill. We sat down with Peralta in Park City to talk about the film, which premiered this week at .

You mentioned at the Sundance premiere that you were hesitant to do this film at first. Why?

Because I play a dual role, director and subject, and I did that in [and Z-Boys]. I was worried that I was going to be viewed as a narcissist. That’s why I put “autobiography” in the title, so if people have an issue they at least know I’m stating it from the top. It was my wife’s idea. She knew my worry. She said, “Look, people write autobiographies all the time, and they make films.”So you know what? It’s a good idea.

You found a wealth of archival footage. Was a lot of it yours?

A lot of it was ours. All these guys lived outside of Los Angeles, so whenever I would fly them in for a contest, I had to photograph them all the time—because I needed the photographs for ads. So they’d come in and shoot tons of stuff. They’d go to the contest, I’d put ’em on the plane, and they’d go home. So we had this archive of probably 1500 photos, 50 hours of footage, over a 10-year span. So I had to go through all this—sort through it—and try to make a story out of it.

Have you been in close touch with everyone in the original crew?

We see each other once in a while, but everyone’s very busy. Being up here [at Sundance], we’re staying in the same home. We’ve not been together like this in over 20 years. It’s so much fun. We stay up every night, drink wine, have the fire going, Tommy’s playing guitar. It’s been a blast.

When you do these movies that rely heavily on archival footage, are you itching to shoot action scenes?

You know, I’ve shot so much action in my life, what I’m interested in now is just telling stories. I just wanna tell a story. If the story requires me to go shoot action, I’ll do it, but so far it hasn’t required that because I’ve been telling stories from the past.

Some of the most suspenseful moments in the film are when the boys come up with never-before-seen moves. Are there as many new moves being invented today?

They are still being invented today, but from what I understand they’re more like variations. These guys came into the sport at a time when the canvas was still very blank. A lot of the maneuvers they developed became iconic, groundbreaking maneuvers that today every skateboarder incorporates. We were just talking about that. What if Rodney or Tony had been born now? They wouldn’t have had that opportunity because the groundwork has been laid. Not to get lofty, but I almost look at these guys as like Chopin. He wrote the etudes, which were the studies. They kind of laid down all the things for future musicians to study. Not to suggest that they’re on that level, but just to say that they had a chance to be architects.

You do get the sense that you’re watching history in the making.

Yeah, what’s interesting is that so much of that footage, when I was making the film, I couldn’t believe they were doing that at such young ages. And I was there. So that was a surprise.

It’s interesting to watch you produce the skate videos, because it’s sort of the equivalent of YouTube today. How do you think YouTube and viral videos have affected skate culture?

I think it’s made the action sport video moot, because from what I understand, kids now go out and shoot a few tricks, post them on YouTube and that’s it. They don’t even do videos because it’s instantaneous. It happens right now. Whereas videos we shoot over a six-month period then release it, and then they play for two years.

Do you ever watch YouTube videos?

I’ve spent so much of my life doing this that I don’t typically [watch YouTube videos]. Once in a while someone sends me a link and says you’ve really gotta see this skateboarder, he’s really doing something different. And I did see a kid this past year from Spain that was doing things like, “Okay, this guy’s on a whole different plain.” Another kid from Japan was doing something so different and unique. Nothing where you go, “Oh my God.” But you could tell this guy was interpreting a different language.

Your films are always set in California, specifically on the coast. Would you like to move elsewhere at some point? Maybe focus on snowboarding, for example?

I’ve never been interested in snowboarding. I don’t know why. There’s something about the white mountain, it doesn’t have enough urban to it. I’ve been asked a lot of times. I don’t know what’s next, either. The things I want to do just require getting money and financing.

What do people approach you for these days?

I don’t get approached too often. I’m kind of on my own little planet. I don’t have an agent or manager. If I wanna make a film, I have to go out and get financing on my own. I’ve been a skateboarder my whole life and we’re kind of outsiders. I find myself like that in the film world, and I finally realized this is just the way it is for me. I’m never gonna be let in the front door, it’s always gonna be in the back. I’m gonna continue to climb over fences. But I realized maybe that’s the way I want it.

You have a knack for getting surfing and skateboarding legends to open up and even cry. How do you generate such intimacy?

Well, you wouldn’t know it from this conversation, but I don’t typically say much. I’m a very quiet person, but since you’re asking all these questions and you seem actively engaged, I’ll talk. Typically I’m the one asking questions. Typically I listen more than I speak, and if I’m at a party I’m glued to the wall, usually by myself. I’m just not comfortable, so I typically just try to engage people by asking them questions.

As you interviewed these men who you’ve known for 30 years, did you come to see sides of them that you hadn’t seen before?

Yes, it’s been really, really incredible getting to know these guys as adults. Really incredible. We were together at a very tender time in their lives and my life as well, and we developed a bond. It is as strong today as it was then, but now I’m getting to know them as fathers and husbands, and we talk about our problems and issues. It’s really, really funny to hear them talk about problems with their own kids.

Do you hear echoes of what you dealt with when they were kids and you were the adult?

Yes. [Laughs.] And to hear what they’re going through with their kids is really funny. It’s good material to share laughs with.

Any specific examples?

Steve Caballero was talking about one of his daughters growing up. She’s 15 and she won’t listen to him anymore, and he’s having to re-figure out how to be a father. He’s gotta back off a little bit. I was just thinking, “Too funny!”

There’s a touching moment in the film when Rodney and Tony buckle under the stress of competition. What role did you play in helping them through this phase?

Well, Rodney was different because when he left, he wasn’t there for me to be there for him. So he had to deal with that on his own. Tony at least was in San Diego, and I dealt with him and his brother. What Tony didn’t talk about was I wrote him a letter saying, look, whatever you need, you do. Because he loves competition—he just needed a break. He had had so much success so fast. He’s not an emotional kid, but when that happened to him—all those kids that spat on him, all those things people said about his dad—he was hurt. So I think he needed time to [tears up]. God, I get… it’s really weird, when we did these interviews I got so involved I became a crybaby. I had to continue to stop because I got so emotional. Anyway, he needed a three-month period to just get perspective on where he was at. What he realized is how much he loves [competing] but needed to figure out a way to come back with a different tack, a different relationship with it.

When you interview Rodney in the present, he’s incredibly insightful. Did you know that about him?

I did not know that he was as articulate as he is. It blew my mind. Before we started shooting we all got together to get any reservations out of the way, and when Rodney spoke, I thought, “Oh my god, we’ve got a film here. This guy is gonna be sensational.” But he was even better than I thought. I had a whole interview prepared for him and he took it somewhere else. Lance did the same thing, as well. He really came and took me a place I wasn’t expecting.

Are you still skateboarding?

I am. I skateboard and stand up paddle surf like a maniac. I’m addicted to it.

Where do you go?

Central California. I ride a small board performance board. I have to do a sport. It’s important for my head, it’s important for my spirit and chemical balance. If I don’t do that, I’ll go to the gym, but I have to keep physically active.

The Ambassador

Satirist and filmmaker Mads Brügger talks about going undercover to infiltrate the African blood diamond business

Traveling by boat

Traveling by boat

Traveling by boatIn , a documentary which premiered at the last week, Danish journalist procures an ambassadorship in Liberia and uses his diplomatic freedoms to infiltrate the blood diamond business. He pays a diplomatic title brokerage $135,000 and, with his newly minted ambassador title, travels to the Central African Republic under the pretense of building a match factory. His real mission is to capture the murky dealings of the country’s diamond industry on camera. This is Brügger ’s second stunt documentary. In his first, , he traveled to North Korea as part of a phony theater troupe—affording a rare look at inner workings of the communist regime. The intrepid journalist spoke with �����ԹϺ��� about his risky seven-week operation in Africa.

It’s astonishing that you pulled this off. Were you surprised that you got as far as you did?

Yes. What was surprising was that I used my father’s name, but if you really deliberately and methodically Googled [the name], you will eventually find out that I’m a filmmaker. I was really afraid that that would happen at one point or another, but nothing ever happened.

Why did you keep the name?

I had to, for these passports for the diplomatic title brokers. They want proof of your identity, so I had to give them a copy of my Danish passport and so on. But you know, it’s what says in , that whatever will make the most money will happen. And if you have a lot of money, anything can happen in Africa.

Why did you decide to make the film?

First of all, I thought in the genre of hybrid role-play films, it would be the next level. Instead of playing a diplomat, I would actually become a diplomat, which raises the stakes significantly and makes everything much more interesting. Also because by becoming a diplomat, I would gain access to a very closed world that you seldom hear anything about. I speculated it would be possible to document and describe the power circles and the kingpins in a failed African state and by doing so, making a very genre-shaking Africa documentary.

You were going undercover in a country where diamond businessmen get assassinated. Were you on edge the whole time?

Of course there were moments of great concern and paranoia, but once paranoia and great concern is a permanent state of mind, you start to relax in a strange kind of way. Also, when I involve myself in role-playing as extreme as this, I become what I’m portraying. Which is a way of surviving the ordeal, but that actually also makes it fun.

Did you break out of character when you were alone?

This sounds very schizophrenic, but I was in character all the time. That’s because the hotel where I had my consulate is like the [hot spot] of for powerful people. They all come to the hotel for meetings and drinks and affairs with their mistresses and so on, and because I was there all the time I had to be in character all the time.

Were there any moments where you were sure you’d be discovered?

A very interesting moment is when I had a reception at my consulate, and one of the guests was a military intelligencer officer from a detachment of South African soldiers who are stationed in the Central African Republic. This man deals directly with President Bozize and so was very influential. He was at the reception and I was trying to keep him at arm’s length, because it is his job finding out about characters such as me. And then he approaches me and says, “Mr. Ambassador, I need to have a confidential talk with you.” And I’m thinking, “This is the end.” We go to a suite next door and he says, “Ambassador, I know you cannot comment on this, but I will say so anyway. I believe that you have all the hallmark characteristics of a highly-seasoned leader of intelligence service, which I believe you are.” And I’m saying, well thank you, I cannot comment on it, but it takes one to know one. And then we laughed in this snobbish kind of way and went back to the reception. Even though it was a harrowing moment, it also made me very proud because it was the ultimate compliment.

In your last documentary, The Red Chapel, you went undercover in . Which documentary felt more dangerous to shoot?

It’s difficult to compare them. In a way, [The Ambassador] feels riskier because in a place such as this, it is so unpredictable what will happen next. You are having whisky sour cocktails with the son of the president. Ten minutes later you could find yourself in a torturer’s dungeon. Not because of something you have said or done, but because somebody told the president’s son something about you which may not even be true. There is no causality principle in the Central African Republic, which makes it quite a challenge to be there.

Did you have a game plan going in, or were you winging it?

I think in terms of situations. I knew I was going to make the matches factory [as a front for his diamond business], and that I had this Indian guy flying in. I knew that I was going to invest in a diamond mine with Monsieur Gilbert. These are the main anchors of the film, and everything else I more or less left to chance.

How much of this was shot on hidden cameras?

Most of the meetings I had in my consulate office is hidden cameras, but when dealing with the Africans, most of the Central Africans didn’t mind. We were filming on this . They look like still cameras. They shoot very high-grade HD. And for a Central African person, that does not in any way relate to film or television-making—they thought Johan [the interpreter] was kind of an amateur—I would tell them in the beginning that he was my press officer, because it sounds swanky, and that he was documenting my exploits and endeavors. But they didn’t care really, so I stopped explaining. And they totally ignored him. So we were able to film scenes where I was thinking, “How come they don’t say anything about the camera?” Even things where Monsieur Gilbert would say, “What’s going on here is very secret. If anyone finds out we’ll all go to jail.” While he’s saying so, the camera is right next to his face. They don’t care. They’re not that media-savvy. Or maybe they are—maybe they are at the next level.

You finally get your hands on some diamonds towards the end of the film, but you don’t reveal what happens to them. Were you worried about implicating yourself?

It’s because I don’t want to take the mystery out of the film. I had to take the diamonds when Monsieur Gilbert brought them to me, to keep up appearances. But I had to get rid of them as fast as possible, because if I were to be stopped by the mining police and they would find them, biblical punishment would rain down on me. So I took them and went alone to a diamond dealer outfit in Bangui, which is run by some Syrian-Armenians, and sold the diamonds to them. So I actually became a diamond dealer, and the money I made I gave to the pygmies to incorporate the match factory.

Can I ask how much money you sold them for?

It wasn’t a seller’s market because I didn’t have the papers — [the buyers] would also have a problem with these diamonds. So I might have made ten thousand dollars?

Some people have expressed skepticism about the authenticity of the film. They think it’s staged, or at least partly staged.

The only thing in the film which is fiction is me and Eva, my assistant, because she is also the production manager of the film. Everyone else is real. Nothing has been staged. Everybody is what they are. It is not a mockumentary, so apart from myself and Eva, it’s really as pure a documentary as you can make. But I understand why they think so, because a lot of the characters in the film are almost like comic book heroes and villains. Monsieur Gilbert and the head of the secret service, they are this close to cliché. If it was a feature film and you would show up with a person such as Monsieur Gilbert, with a machete scar and a gold tooth, you would say this is too much, you have to tone it down.

Beasts of the Southern Wild

A movie about climate change wins the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance

is a climate change doomsday tale like no other climate-change doomsday tale—think �����ٲ��� with an environmental twist. The terrifically unpredictable film evokes a visceral concern for what lies in wait when ecological disaster strikes. It then asks how one is supposed to come to grips with the notion of impending catastrophe. The answer is: celebrate the hell out of what you have right now.

The movie centers on an impoverished but wildly spirited community in a fictional Louisiana bayou called The Bathtub. Early on, a schoolteacher ominously instructs her kids that climate change is transforming the ecology of their community. “Y’all better learn how to survive now,” she warns. To ratchet up the looming threat, scenes of life in the bayou are interspersed with surreal cutaways to a pack of pre-historic aurochs that, once frozen in glaciers, have now been loosed from the melt. Throughout the film, the ferocious beasts stampede closer to the bayou, a metaphor for approaching disaster.

When the storm finally hits, it floods The Bathtub’s ramshackle homes, transforming lowlands into murky rivers and wiping out the animals and plants once relied on for food. Rather than despair, the Bathtub’s steely citizens drink and laugh and feast on the grub that remains. The two main characters—6-year-old Hushpuppy () and her mercurial father, Wink ()—will not be fazed. They troll the water for catfish, which they hunt by hand. Wink tries to drain the bayou by blowing a hole in the levee. “I got it under control,” he roars. Well, he doesn’t, exactly—he’s actually dying—but that doesn’t make his attitude moot.

In press notes for the film, director writes, “With the hurricanes, the oil spills, the land decaying out from under our feet, there’s a sense of inevitability that one day it’s all going to get wiped off the map. I wanted to make a movie exploring how we should respond to such a death sentence.” If you haven’t already gathered, this is not a pragmatic exploration of ways to avert said death sentence—for those answers, try a documentary. Instead, Beasts offers a much more esoteric take on climate change, and it’s well worth a watch when it comes to a theater near you.

Chasing Ice

Photographer James Balog and director Jeff Orlowski talk about the grunt work behind their new documentary project, a beautiful and frightening chronicle of so much melting ice

Chasing Ice

Trekking in

Trekking inChecking the cameras

Checking the cameras

Checking the camerasChasing Ice

In the water

In the waterDOCUMENTS THE WORK of , The North Face sponsored photographer who launched the in 2007. The goal? Illustrate the effects of climate change. The method? Place 27 time-lapse cameras at receding glaciers around the world to record their history. The results are magnificent—and terrifying. We spoke with Balog and director about the nitty gritty detail that went into the making of the film.

What was the most remote camera location, and what was the journey like to get there?

Orlowski: Getting to Greenland alone you have to go through Copenhagen now, so we would have to fly from Colorado to the east coast to Copenhagen, back to Kangerlussuaq.

Balog: Kangerlussuaq is on the west coast of Greenland. It’s sometimes a couple of stops to get from Copenhagen to there.

Orlowski: Then another flight at least in Greenland, then helicopters.

Balog: Or boats or dog sleds to get out to the actual camera site. There’s one site where there’s two cameras currently up in northwestern Greenland, at Petermann Glacier. That is up in a place where there is probably no human being except maybe every second or third year. It’s really way, way out there. I can’t tell you what the latitude is. It might be about 78 or 79 degrees north up in the northwestern corner of the country. There’s no villages within hundreds of miles, no military bases or weather stations or anything. It’s just out there.

What are some of the more harrowing conditions you’ve had to endure when trekking out to the cameras?

Balog: I think temperature-wise it would be Greenland in the wintertime, and that was minus 30 degrees, basically. Wind-wise and storm-wise, it’s probably Iceland.

Orlowski: Adam and I had some bad winds in Greenland, the katabatic winds just coming off the glacier. It’s a temperature difference that creates these really high-powered winds. We were camping in 90-mile-per-hour winds. Our tents broke, the aluminum poles sheared in half. We lost a couple tents from heavy winds. The temperature in Greenland in the wintertime, those were minus 30 degree temperatures and we got frostnip touching cameras. I thought I was gonna die one night because our heater wasn’t working, and I woke up in the middle of the night because my teeth were chattering so much—that’s what woke me up. There were some cold, cold conditions.

Balog: And Iceland has incredibly violent storms. There’s a volcano right up above the glacier and the air masses tend to come from over that volcano and down to where the cameras are—and you get these violent bursts of wind and storm that come in these pulses. It’s kind of uncanny how it gets this rhythm going. It’ll be mildly unpleasant for 15 minutes, then for about five or 10 minutes you’re getting ripped every which way and eaten up by the snow and the wind. In the summertime it’s rain, but it’s almost as violent.

Orlowski: When we’re in Greenland, we are out in very, very remote locations. A helicopter drops us off. We’re there camping for a week with all of our provisions. There are some landscapes where there’s no wildlife at all. You’re just out on the ice. All you hear is water. And there was one time where, due to bad weather, a helicopter couldn’t come pick us up. James was stuck there for five days without any opportunity to get back. It was full-on, “Sorry we can’t get you, we’ll get you in a couple days.” Fortunately he had enough food to last.

How much does your gear weigh altogether on these trips?

Balog: It just depends on what the objective of the trip is. I don’t think we ever left the Denver airport without 800 pounds or 1,000 pounds of gear. In the beginning of the deployment, when all that stuff got shipped to Greenland especially, I don’t know. 1,500 pounds? 2,000 pounds? It goes up on U.S. Air Force flights that go from a National Guard base near Albany. It gets airlifted on a C1-30 up to a base on Greenland. Then we have to put it on the commercial flights to go further north. The logistics are crazy. It’s all you think about for a while.

Orlowski: The first time we went to Greenland, James made me and the whole team look at everything we were bringing. We laid everything out in James’s garage and he approved everything that was coming. I thought, “Why are we going through this level of scrutiny?” Then I learned the helicopters costs $4,000 an hour and we were paying thousands of dollars on excess baggage on every leg of these trips. Hundreds of dollars on some, thousands on others. We were paying per kilogram so every extra thing with us counted. You were bringing only the absolute necessities. We also get very good at hiding our excess weight from the airlines. When you go to check-in, they give you baggage tags on Air Greenland for how much weight you’re allowed to bring onto the plane. So we would each check in separately. We would hide all our extra gear that we were gonna carry onto our plane with somebody. We’d check in individually with a very small lightweight bag that they would approve, and then we would try to sneak onto the plane with all the extra camera gear, lenses, bodies, video cameras. And most of the time it was successful. But it became an art form of sneaking the camera gear onto the plane.

Tell us about your cameras. James, you had to build them yourself because they didn’t exist.

Balog: It was about four-and-a-half months worth of developing the technology for this thing, at least in the first wave of it. You have two basic problems: One is the electronics of telling the camera when to fire, and giving it power so that it can fire. And then the other problem is protecting the equipment against the weather. I was doing a lot of things by trial and error to see what would actually work. And it was really complicated.

How did you anchor and winterize the cameras to withstand harsh conditions year-round?

Orlowski: They had to withstand 200 mph winds and negative 40-degree temperatures. And James had to build a system that could endure huge variations in temperature. I think a lot of that was trial and error. And when we installed stuff, we learned as we were installing them what was working and what didn’t work, and we ended up creating a system that could be modified for almost any landscape. The first time we went to Iceland, we were installing a system we had designed for tripods. We were gonna use the tripods, secure them to the ground, and when we got there we realized the ground was too soft. The tripods would shift and they wouldn’t stay.

Balog: There wasn’t nearly as much bedrock to stand these things on as we’d thought.

Orlowski: So we ended up having to mount them into the mountainside, and we had to completely redesign the system. We kind of created two systems: one that could be mounted against a cliff face or a wall, and one that could be mounted directly into the ground. And those two systems allowed us to work in pretty much any environment.

Balog: We discovered the first problems in Iceland. That was March of 2007. It was the first field test of all these ideas. As soon as we got there it was like, “Oh shit.” All this thinking and all this work to build a support system, and all the boxes and boxes of gear that went with that idea. And it was already ordered and billed for 25 cameras. I had 25 cameras worth of gear that was suddenly junk. We ended up donating it to the University of Colorado’s engineering department. In any event, we were running down to the local hardware store 50 miles away, trying to cobble together pieces and parts in new tools and all kinds of stuff to build a new theory about how to put these up on the cliff faces along the volcano.

Orlowski: And a hardware store in Iceland is not exactly a well-provisioned hardware store. It was definitely jerry-rigging a system that would work, that we later improved as we went back and re-tested them. That very first camera we installed, it was on a cliff and got completely knocked off. This rock fell, cracked a hole in the top of the camera box and the whole thing sheared right off of its mount. We’ve had cameras buried under snow in Alaska, under 20 feet of snow. The cameras were mounted to bedrock using the bolts you would use to go rock-climbing with, that are designed to support thousands of pounds of weight as you pull on them. We had four of those in the base of the camera and another four cables securing this thing, but when we went back to one of these systems, we had to dig it out from under the snow. The entire system was shaking. It was completely loose. The weight of the snow had pulled the bolts out of the rocks.

You’ve experienced so many setbacks along the way. Were there moments where you felt you should scale down the project?

Balog: There were a lot of times when I really felt like I was over my head, because of the electronics. Not only did I not know about some really obscure questions of how electrical systems worked, I was kind of mentally resistant to learning about it. And when I tried to learn about it, I found the guys who were trying to explain it weren’t doing a very good job. They had been in an electronic world for so long, they couldn’t speak to laymen about it. So eventually I got aggravated with the electronics, as I so often do still today. It was like, “God, this is just driving me crazy that I have to do this.” But as with all the big projects that I’ve done, it pushed me into new creative and technical territory in pursuit of the aesthetic ideal I was after. So I kind of had to grit my teeth and bear it. But believe me, it was about 15 times a day I was thinking, “Geez, I’m over my head on this,” or “Dammit, I don’t like this,” or “How did I ever get involved with this craziness?”

How frequently do you check on the cameras and upload the photos?

Balog: It depends on where they are. If the site’s relatively accessible, like they are in Iceland, we can get there three or four times a year. Greenland it’s once a year, Montana it’s once a year.

How many photos do you take in one year?

Balog: It depends on latitude and how much daylight there is, but one year is equal to approximately 4,000 frames that we’re shooting once an hour. That’s 4,000 frames per camera.

Orlowski: How many frames totally have been collected so far?

Balog: We’re somewhere in excess of 800,000. We’ve kind of lost track, but now each camera is shooting every half-hour in most cases. Some are shooting every 20 minutes, but basically every half-hour it gives you about 8,000 frames.

Do you get excited when it’s time to visit a camera and retrieve new photos?

Balog: It’s like opening presents on Christmas morning. Every time you go to a camera, it’s like, “Wow, here we are, here’s the goodies, let’s see what we have.” And of course at the same time, you always have this sense of dread in your gut, like oh god, what if it didn’t work? That anxiety about the failure was much more acute in the beginning of the project, when we really needed to have the technical things working. We needed content. In the world of academic science, if you do the experiment, you get points in heaven. But in the world of picture-making, you don’t get points in heaven for experiments. You only get points in heaven for having a picture.

Which glaciers have shown the most alarming decay?

Balog: It’s hard to define that because are you dealing with volume of ice? Or are you dealing with percentage of change in relation to the size of that glacier? Because a little glacier can have a lot of retreat in relationship to its size. On a percentage basis it can be enormous, but it doesn’t deliver the volume of ice that a big glacier having a little bit of change is doing. So how do you describe it? I think one of the most dramatic examples certainly is Columbia Glacier in Alaska. That’s now had almost three miles of retreat since we’ve started the project. We actually just got an email from one of our partners in Anchorage over the weekend. There’s actually a beach that’s now formed where the ice used to be.