In late 2008, faced a major life decision: Was she going to keep up with her increasingly famous rock-climbing son, Alex Honnold, by getting��a foothold into his risk-taking world, or was she going to lose him to the mountains?

She knew that scaling sheer rock faces with his willpower and wits was what her son did well. She’d seen his image in so many magazines following his climbs, including his free solos of such exotically named walls as in Zion National Park,��as well as both and ��in Yosemite.

But when he returned from yet another successful expedition someplace in the world, she couldn’t relate to his stories. “It was like another language,” said Wolownick, a writer and career foreign-language professor who lives near Sacramento, California. “And like I am when I’m confronted with any new language, I want to learn it. So that when he came home, I’d know enough to both celebrate the victories and commiserate with the defeats��and just be a part of his life.”

A decade later, she’s shown that if she hasn’t completely mastered the nuanced phraseology of rock climbing, she’s pretty darn��proficient. Last year, at age 66, Wolownick became the oldest woman to ascend Yosemite’s iconic El Capitan. She has also emerged as a survivor who overcame the emotional damage of a dysfunctional marriage, a dedicated mother who raised two kids with extraordinary athletic skill sets: Alex the rock climber��and , a runner and cyclist who has passed her passion for both sports on to her mother.

Last year, at age 66, Wolownick became the oldest woman to ascend Yosemite’s iconic El Capitan.

Even in retirement, Wolownick regularly runs regional road races and cycles whenever her schedule permits. But for the most part, whenever she finds a free moment in good weather, she heads for the nearest crag for yet another rock climb.

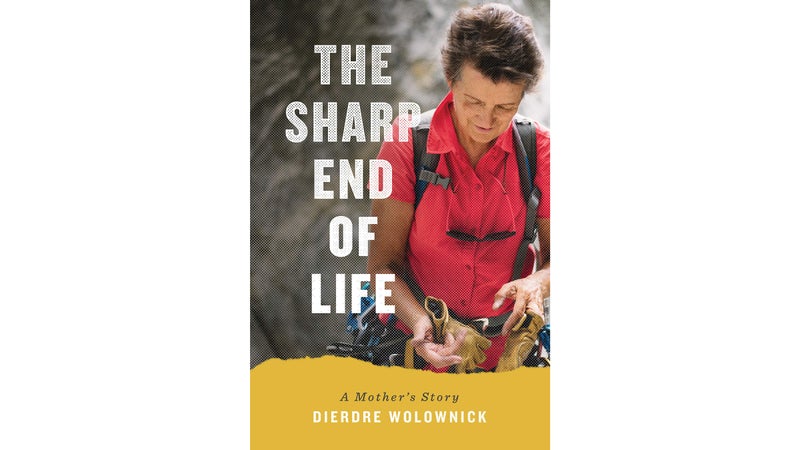

This month, Wolownick published , a memoir about her metamorphosis from a self-effacing wife in an unhappy marriage to a confident athletic role model for her generation.��

To say the book is solely a chronicle of rock climbing is like claiming is all about riding Harleys. It’s a mother’s tale of late-life role reversal, how she opened herself up to learn important lessons from her grown children. “The book is about being able,” she says. “It’s about not listening to the naysayers and listening to your heart instead. That’s how you achieve stuff. I was raised in the other extreme, taught to shut up and be obedient. Girls just didn’t do certain things.”

Wolownick describes her years of coping with the antics of her resilient son, who��she recalls reached age four probably thinking his name was “Alexander—No!” He regularly clambered to the top of kitchen appliances and various playground equipment.

“Alex, don’t go up there,” she’d say.

“Why, Mom?” he’d answer. “It’s really easy.”

Daughter Stasia, two years older, was always the “diplomat” who seemed to know intuitively when Alex had pushed his mother too far. She’d take his hand, Wolownick writes, “and gently lead him away from the scene. Somehow, she always knew.”

Her memoir also chronicles the demise of her marriage to Charles Honnold, whose unexplained anger and brooding emotional distance she now believes were the result of Asperger’s syndrome. She likens tiny cracks that began to emerge in her marriage to being “like the hairline webs that cover the bottom of your great-grandmother’s soup tureen or sugar bowl, but that don’t stop you from using it.” Following her eventual divorce and Charles’s death from a heart attack in 2004, Wolownick focused her attention on her two college-aged��children, who in return propelled their mother to find a new inner strength.

Stasia became a one-woman cheering section after the divorce��and later turned Wolownick on to the world of jogging, then running, and eventually marathons, which she soon found “contagious.” Alex did his part, too. When Wolownick came home announcing with pride that she’d just run a mile, he��took��a nonchalant bite of a cookie and shrugged. “Cool,” he said. “If you can do one, then you can do one and a half.”

Alex later introduced his mother to the vertical pursuit of rock climbing at the gym. “I was 34 years older than my son, who was already an adult; he was babysitting me,” she writes. “My chicken arms were weak, my body was flabby, and I knew I must look silly and awkward to him as I struggled up the artifice wall. But those thoughts fell away in a few seconds.”

In raising Alex, she learned how to forge her own path and trust her own judgment��rather than following well-meaning advice about the norms of parenting, because those norms didn’t apply to her son. One friend and mother of a small boy suggested Wolownick��put Alex on medication, advice she��dismissed out of hand. When friends visited her home and saw him doing something dangerous,��Wolownick would see them leap to their feet and yell at Alex, “Watch out!” Still, she kept making the coffee, believing that Alex would not push his limits.

In her memoir, Wolownick details her ascent of El Capitan and the newfound ability to enter “the zone” that allowed her reach the top. In the past, she’d only reached that zen state while painting, running, and playing the piano.

She also tackles a comment she often hears regarding her relationship with her famous rock-scaling son: “How would you like to be that kid’s mother?” “I trust his judgment. It has to come down to that,” she says. “He’s the only one capable of knowing if he can do a climb. And no matter what I or anyone else says, he’s going to do it anyway.”��

Wolownick intends this as a book for everyone—retirees, parents,��and rock climbers alike. But I’m not a parent and I don’t climb, so I was less interested in the details of summiting any face or dealing with a precocious��yet gifted child. Where the book gripped me best were the parts where Wolownick fights her way through an emotionally abusive marriage to find a place to breathe, as both a woman and mother. The challenges she overcame seem to me as challenging as any rock wall.

These days, Wolownick is at home recovering from foot-reconstruction surgery to repair a chronic condition. But she’s impatient. With the publication of her new memoir, there are book signings waiting in the wings. There are also roads to be run and��rock walls to be climbed—a return to a��demanding athletic life that her own two children have taught her to cherish.