Credit the Labrador and the horn hunters that , 45, the infamous Mountain Man of southern Utah, is currently cooling his heels in the Sanpete County Jail in Manti. On March 29, Good Friday, Dale Fuller and his 15-year-old son, Jordan, were scouting for shed elk antlers below Skyline Ridge on the eastern side of the 10,000-foot Wasatch Plateau in Emery County. Walking down the narrow Dairy Trail, they came across a man loaded for bear and headed upcountry. He was scruffy, in his mid-forties, with a gray-and-blond beard. He carried a fully loaded pack. His sidearm was not unusual in Utah, but what was noticeable was the assault rifle slung over one shoulder. Jordan’s two-year-old brown Lab, Duke, growled—and continued growling for the whole encounter, even after Jordan tried to quiet him.

One of the camps Knapp left behind.

One of the camps Knapp left behind. The first confirmed image of Knapp, captured by a wildlife cam.

The first confirmed image of Knapp, captured by a wildlife cam.“The guy seemed way friendly,” Jordan told me. They talked about snowpack levels—this area was at 60 percent of normal, and the trail was an Easter succotash of mud, corn snow and vegetation—and whether or not they’d seen anyone else in the area. Dale asked what he was doing headed into the high country. “Going camping,” Knapp responded. “I’m a mountain man.” Either that or, “I’m the Mountain Man”—the Fullers couldn’t tell.

��“I don’t plan on shooting you guys,” Knapp continued when Duke would not stop growling.

Nobody had mentioned shooting anyone. But of course, the Fullers—who were armed themselves, but lightly in comparison to the assault rifle—had heard of the Mountain Man, and when they got within cell service, they called a friend who is married to an Emery County sheriff’s deputy; the deputy forwarded them photos.

It was him all right. For nearly seven years, the , breaking into cabins, stealing firearms, and roaming on foot between 3,000 and 10,000 feet in a nine-county area the size of Delaware—wild country made wilder by winter mountain weather. South to north, his territory covered 180 miles. In the southwestern counties of Iron, Kane, and Garfield—his main range for much of that time—Knapp was suspected of dozens of cabin burglaries. He faced 19 felony charges and ten misdemeanor burglary and theft charges in those three counties alone.

That was before he shot at the helicopter.

Over the Easter weekend several residents opening up their cabins after the winter discovered evidence of an unwanted guest. Investigators fingered Knapp for a break-in near Joe’s Valley Reservoir—about 15 miles north of the Fullers’ encounter, near the border with Sanpete County—where a crowbar was left at the scene. On Easter Sunday, they responded to another break-in report in the same area; this time guns had been taken.

The Fullers’ sighting gave authorities the fresh lead they needed. Officers on snowshoes slowly tracked Knapp over three days and 15 miles; his bear paws led into Sanpete County and to a cluster of 13 cabins near 9,000 feet at Ferron Reservoir, on the shoulder of Ferron Mountain.

On Monday, April Fool’s Day, a 50-person task force that included members of seven county sheriff departments, the (DPS), Adult Probation and Parole, and a half-dozen federal agents from the U.S. Marshals Service, gathered at the Sanpete County Sheriff’s Department to strategize. Emery County detective Garrett Conover told me that they discussed the February cabin standoff in California that ended with the death of ex–Los Angeles policeman-turned-murderer Christopher Dorner. When authorities located Dorner in a cabin near Big Bear Lake, a firefight ensued; tear-gas canisters caused a fire that burned the structure to the ground. Dorner was found dead. That’s the scenario the Utah team most wanted to avoid.

The next morning, April 2, just after midnight, the lawmen headed into Ferron Canyon in snowcats and on snowmobiles with two Utah DPS helicopters at the ready, then quietly took position on snowshoes in the frozen dark, even though they weren’t yet sure which of the cabins Knapp was inhabiting.

It was part of the plan that the racket from one of the helicopters would alert Knapp. It did. The first helicopter came in from the east; they could see Knapp on a cabin’s porch. “At about nine in the morning, Knapp is out chopping wood for his morning fire when this big-ass bird comes in over the trees,” U.S. Marshal Michael Wingert, the lead federal agent assigned to Knapp’s case, told me. “He grabs his rifle and shoots at the bird.”

Knapp, who was also armed with a handgun, squeezed off several rifle rounds. The men in the helicopter saw him reload. The fugitive strapped into his snowshoes, grabbed his rifle, and took off running to the south. After an exhausting 100-yard dash, he encountered Emery County Sheriff Greg Funk. Knapp raised his rifle. Funk fired and missed. Knapp broke back to the north and ran into a line of lawmen. Knapp realized he was heavily outgunned—and surrendered.

“You got me,” Knapp told arresting officers. “Nice job.”

The high-country cat-and-mouse game was finally over. But for seven years, Knapp had had an incredible run in the wilderness. Here was a lone man on snowshoes running circles around sheriffs and marshals with little but his physical fitness and backcountry savvy—an alpine athlete living on rabbit and Dinty Moore stew. He’d earned a sort of grudging admiration from the men on his tail; Knapp seemed to understand that you didn’t have to outrun the dogs, you merely had to outrun the handlers. He was good at staying ahead of the handlers.

FROM MEDIA COVEREAGE AND REACTION IN UTAH, you might have thought the authorities had captured Bigfoot. Wanted posters had been tacked up in gas stations from Kanab to Payson. Hikers and hunters grew leery of heading into the high country, and families became shy about visiting their weekend cabins. The fugitive had even acquired a Facebook page, set up by an admirer, filled with mountain-man poetry and clumsy odes to outlaws and Waylon Jennings. The name Unabomber was bandied about. Some recalled the Olympic Park Bomber, 46-year-old Eric Rudolph, who hid for five years in the North Carolina woods, dumpster diving and swiping vegetables from gardens. Or fellow Utah fugitive Lance Leeroy Arellano, who disappeared into the desert in his silver Pontiac after shooting a state ranger in 2010.

Knapp didn’t have a known history of that kind of violence, but he commanded respect. “I could take every cop in Utah who’s comfortable on a pair of snowshoes up there right now and not find him,” U.S. Marshal Wingert told me last year. In a year and a half of tailing Knapp, Wingert became the Pat Garrett to his . “You give this guy a day and he’s 15 or 20 miles away. There’s people who can survive a night out—say they break a snowshoe binding or lose the track on a snowmobile,” Wingert said, “but to actually stay out there for months and months and years on end—this guy is as close to Jim Bridger as we’re ever gonna see.”

In summer, Knapp lived in his own homemade camps; over the years deputies found bivouacs, usually with a blue tarp, in the aspen trees, stocked with guns and, in one, a copy of Jon Krakauer’s . Several of his high camps were discovered by cougar hunters, who hunt in high, rocky terrain. As far up as 9,000 feet, they were relatively sophisticated shelters with framed doors and rocks and wood and earth.

In winter, the Mountain Man made himself at home. His usual mode of entry was to break a window or door pane, twist the lock, and let himself in. Sometimes he’d wipe his boots, sometimes he wouldn’t. He made soup from cans and helped himself to coffee. Knapp liked sardines, mayonnaise, and especially liquor: if there was a bottle of spirits, he might drink it and rend the place with bullet holes. He might replace the firewood he burned. Sometimes he did his dishes, but he never put them away. He liked to steal radios, listening on local AM stations to erroneous reports of his own whereabouts.

For much of that time, the Mountain Man behaved in a Robin Hood-esque manner. He took from the relatively wealthy cabin owners and gave to—well, he gave to himself, a poor guy living by his wits and fitness on the land. Then, in early 2012, when Knapp’s identity was verified by investigators and reported by local media, his reputation as a harmless survivalist began to slide. In the cabin of a former Las Vegas police officer, he made a crucifix with knives on the bed. At times he appeared angry at Mormons—he shot holes in a portrait of Joseph Smith and ripped up the . He cost one cabin owner thousands of dollars in smoke damage when he closed the flue before vamoosing. He traded guns with another—leaving his old .303 British and taking a sexier Remington. He crowbarred into a gun safe, laid all the arms on a table, and took none. In another cabin, he removed the grips from all the guns, but left them. He placed food cans behind kitchen drawers so they wouldn’t close. He defecated on a porch; he also shat in a pan and left it on somebody’s kitchen floor.

Authorities labeled him ‘armed and dangerous’ in January 2012, reporting that the Mountain Man had been leaving threatening notes in cabins or outside scrawled in the dirt. The tune was always the same: “Get off my mountain.”

FOR MOST OF THOSE SEVEN YEARS, lawmen were hunting a ghost. As early as 2007, they suspected that one man was breaking into properties over a big area, but damned if they knew who. “Even when we got a tip, we were always one week behind,” Kane County Chief Deputy Tracy Glover told me. The Mountain Man stuck to ridge tops, avoiding established trails. He walked on vegetation to avoid leaving an easy track. He slipped from heavy hunting boots into size-10 sneakers to minimize his footprints.

Up until last year, Knapp mainly roamed 1,000 square miles of southwestern Utah, from the Arizona border north into Zion National Park and onto Cedar Mountain above Cedar City. His habitat ranged from alpine forests to the sparsely populated desert. He was known to walk to town—St. George and Cedar City—and hang out with the homeless population and make phone calls to his mother in Moscow, Idaho, then head back into the wild.

Then investigators got a break in December 2011, when a motion-activated camera outside a cabin in Kane County captured the image of a man with neck and hand tattoos and a ginger goatee. The man wore forest-camo hunting outerwear that hung on him. A camo fleece beanie. A Remington 600 bolt-action rifle. A long hunting knife in a leather sheath. Purple aluminum snowshoes.

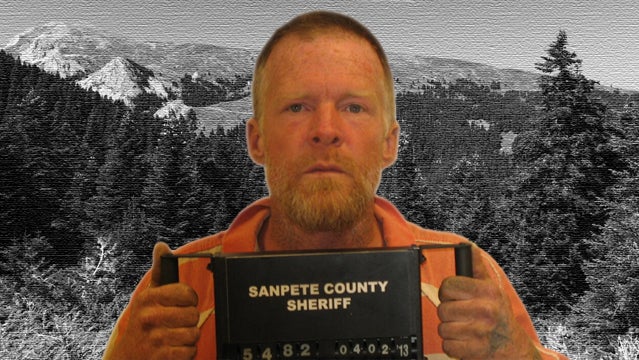

A month later, fingerprints obtained from a broken window pane in 2009 matched with then-44-year-old Troy James Knapp, five feet ten inches tall, approximately 150 pounds, with hazel eyes. This led the cops to mug shots taken in Inyo County, California, in 2000. Knapp’s hand and chain-link neck tattoos matched the Mountain Man’s.

Knapp had been in trouble since his high-school-dropout days in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where in 1986 he was incarcerated for four years for breaking and entering and receiving stolen property. After that, he drifted, working odd jobs and living for a time with one girlfriend and then fathering a daughter with another in 1995. He was charged with harassment in Seattle in 1997 (that charge was eventually dismissed with prejudice). He lived briefly in Salt Lake City in 1999.

His stepdad, Bruce Knapp, a sportsman, had taught young Troy wilderness skills—hunting, trapping—and that became Knapp’s M.O. In September 2000, he began living the outlaw life in Inyo County, camping near the town of Bishop. There he was arrested on charges of felony burglary for stealing from the Inyo County Solid Waste facility and the Mount Whitney Fish Hatchery in Independence. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Knapp stole a pair of boots from a game warden’s pickup near the hatchery, even as they were looking for him. A deputy’s report from 2000 quotes Knapp: “I did not want to hurt anyone.” Then, in 2004, after spending four years in jail, Knapp broke parole.

Southern Utah, his next stop, is a lot like : It is high alpine, but also full of slot canyons and rock chicanery and deserts side by side. One day it’s sunburn, the next, frostbite. In Inyo County, the Sierras quickly drop to Death Valley. And the county had its own backcountry badass: the Ballarat Bandit, George Robert Johnston, who eluded law enforcement for years while camping and squatting in remote southeastern California and western Nevada before he shot himself in the head with a .22 in July 2004.

Utah authorities thought they were hot on Knapp’s trail in late February 2012, when a resident shoveling snow spotted a camo-clad man with a large-caliber rifle slung over his shoulder. A two-day manhunt went down above Cedar City, including Iron County Sheriff’s deputies, Cedar City Police, and even the campus cops from . A helicopter scoured a ten-mile radius.

In the end, the manhunt only fueled the myth. Locals were left wondering how anyone could have eluded a helicopter with infrared technology and 30 men on foot.

By this time, I’d become obsessed with the Mountain Man myself. I grew up on stories of the Mad Trapper of Rat River, a legendary Canadian survivalist fugitive from the 1930s, and Claude Dallas, the poacher who evaded capture for over a year after killing two game wardens in 1981 on the Idaho–Nevada border. Fifteen years ago, my wife and I lived in a remote cabin in northern Utah, where we’d ski up to and peer into the fancy vacation cabins that hibernated over winter. What a resource, I thought, for a homeless person with just a little wilderness savvy. That’s where I’d head, I figured, if a private apocalypse got bad enough. I didn’t see it as survivalist prepping, rather temporary existing. You could escape the grid there, go analog, at least for a while.

So this past April, I traveled to Knapp country. At that point, I’d been tracking him—via wire stories and local knowledge—for nearly four months. I had a wall map full of enough Knapp-sighting pins it looked like a game of Battleship. One thing was for certain: the guy was in fighting shape. I watched him grow thinner from mug shot to moose camera to security surveillance digital images. But still he was capable of humping a heavy pack over mountains for twenty miles a day, many days in a row.

KANE COUNTY IS 4,000 square miles, the size of , but there are just over 7,000 people living there, half of them in the county seat of Kanab. The sheriff’s department boasts 13 sworn officers, not including the uniformed mannequins in the marked SUVs parked at the city limits of Mount Carmel and Orderville to discourage speeders. This part of the state has become Mexican cartel marijuana country, and I was reminded of what Marshal Wingert had told me before I arrived: “If we have trouble finding cartel-size grow operations in that country, imagine trying to find one camouflaged guy on foot who doesn’t want to be caught.”

The bull’s-eye of Knapp country seemed to be the Cedar Mountain area above Cedar City, where hundreds of seasonal cabins are tightly surrounded by Dixie National Forest land. The area includes 11,307-foot Brian Head Peak, the Brian Head ski resort, and Duck Creek, a little village where you can hire four-wheelers or snowmobiles and a guide.

Since the first WANTED posters went up in Duck Creek in January 2012, the Mountain Man had become something of a cross between Sasquatch and Jeremiah Johnson. Cougar hunters saw him walking a ridgetop before he vanished. A cowboy reported running into a “suspicious” mountain man packing his gear on a pair of mules. Strange campfires were seen on the mountain above Cedar City at night. Dozens of people saw the Mountain Man riding his mountain bike through town. Kids liked to spot him in trees. My favorite was a dog let outside at 4:30 every morning that returned at 6:30 reeking of campfire smoke.

In Duck Creek, a sledhead at a snowmobile shop told me that I needed to find Rosey Canyon, up the North Fork of the Virgin River, because that’s where I’d find a guy named Ken Moffett, the caretaker for several cabins. Back in February, he said, Moffett had tracked the Mountain Man in the snow, on foot, for seven miles. This would make Moffett, at the time, the guy with the closest encounter with Knapp. “But honk your horn at the mouth of the canyon,” I was warned, “otherwise he might think you’re the Mountain Man and shoot ya.”

The road led through Springdale, the gateway village to Zion National Park. At a bar and restaurant called The Spotted Dog, I met two cabin owners, Robert “Roberto” Dennis, 40, and his sister Wendy Dennis, 41. Like many of the locals, they were curious and a little anxious and wanted to check the family hunting cabin to see if anyone had broken in. “We keep guns up there,” Wendy told me. “They’re our shitguns, but still.”

We climbed into Roberto’s 1994 GMC pickup. Wendy took the jump seat; Duke, the Lab-pit mix, got the middle, where he slobbered on my maps. Southern Utes do not leave home without some kind of firearm, but Roberto packed light—a toy-size .22 caliber short-barrel Beretta he called a hooker gun. We were headed 25 miles higher up, toward Cedar Mountain. It was drier than a Mormon wedding and the truck left a veil of dust.

Roberto and Wendy had found something odd in the forest the hunting season before: a Hefty bag hanging in a 40-foot ponderosa pine. They thought it was trash, but the bag contained a knit beanie. Felt boot liners. A camo sleeping bag. A pair of nearly-new size-10 sneakers. Matches and chainsaw sharpeners. This didn’t say hunter or Boy Scout. It said transient—alpine homeless. But why up here, so far from Interstate 15?

Many of the cabins we passed were homogenous: attractive, clean, and new. The Dennis cabin was different, a cobbled utilitarian compound with a generator shed where they hang the venison and an antique propane refrigerator that sealed the silverware and some warm Budweisers from the mice.

Something had been inside the Dennis cabin for certain, but it wasn’t human. There were rifle cartridges and Tammy Wynette eight-track-tape cartridges strung from hell to breakfast. Turds the size of licorice snaps were strewn all over the kitchen table, like a taunt. Wendy located a dusty green bottle of Jägermeister. “Gotta take a shot at the cabin,” she said and did. The mood was one of light relief, but mostly disappointment—disappointment that a varmint had ransacked the place, but also that the infamous Mountain Man had skipped it for a stay-over.

We got back in the truck and turned upcountry to Rosey Canyon, driving 15 more miles, over dirty snow drifts and through braided streams, until we came upon a man standing in the middle of the two-track road.

“Are you Moffett?” I said through the truck window.

“Yes I am,” he said.

Moffett, 61, was clean-shaven with long gray hair. “We’ve had a problem now for seven years,” he said. His encounter had taken place six weeks prior, in mid-February, a week before Knapp was fingered by name. “I caught these weird tracks,” Moffett said. “This guy was sneakin’ around bushes,” he said as he pointed up the road toward the neighbor’s place. “Sure enough,” Moffett said, “there’s these tracks going around all their windows.”

Moffett had hopped on his four-wheeler and motored up the road. “Went up to check on the Stuckers’ place,” he said. He’d walked the property and circled back. Then Moffett told us the strange thing. “I noticed there were carefully placed snowshoe tracks on top of my boot tracks.” The mountain man had sent Moffett a message in the snow.

Moffett is the kind of Abbey-esque new-western character who might have appreciated Knapp’s gift at surviving solo, but he too had tired of the Mountain Man’s antics. “Give him a can of soup, who cares,” Moffett said. “But I think he’s getting more and more disturbed. He’s progressively upped the ante here. It’s like he’s getting paranoid now. I don’t wanna walk up on him and I don’t want one of my neighbors getting shot.”

THAT’S WHAT IT SEEMED LIKE was going to happen, as Knapp got angrier and messier. After he was ID’d, he left several seemingly drunken notes, including this one from a cabin in Kane County: “Hey sheriff; fuck you! Gonna put you in the ground! It’s better, these times, to be a ditch digger, septic cleaner than a pig.”

Authorities were unsure, however, how violent Knapp was. Marshal Wingert told me about a homeless man in , along the Virgin River, who in 2010 said that he was brutally beaten by Knapp with a rock over some camping gear. The man declined to press charges.

Knapp’s time on Cedar Mountain also coincided with a strange, cold-case homicide straight out of a Coen brothers’ movie. In 2007, during hunting season, the partially buried body of 69-year-old Kennard Martin Honore of San Clemente, California—who’d leased a cabin from the Forest Service—was found in the cinder pits near Navajo Lake, west of Duck Creek. Honore had died from a single gunshot wound from a small-caliber rifle and been hastily buried. Kane County deputies could find no motive and no sign of robbery. There were a lot of hunters in the area, so it could have been a stray round. But the small caliber doesn’t make sense for deer, and the quick gravework doesn’t make stray-shot sense. No evidence connects Knapp to the case except that he is believed to have been in the area at the time. Still, Wingert told me, “It’s kind of an unusual coincidence.”

Last April, I spoke to criminal psychologist Eric Hickey, dean of the California School of Forensic Studies at Alliant International University in Fresno. “The isolation is probably costing him,” said Hickey, who worked as a consultant on the Unabomber case. I told him about how Knapp’s bad behavior had seemed to escalate, about his threatening note to the sheriff and the pan of scat in the kitchen. “Most people are not good at being isolated like that. He’s acting out. I suspect he has no control.” Hickey said the scat in the pan was a signal. “This is a signature.”

��“The truth is,” said Hickey, “if law enforcement decides to go after him, they can track him. I guarantee, if he hurts somebody they’ll go after him.” But he didn’t, and Knapp’s trail was cold all last summer.

Then, in October, he resurfaced. Knapp had moved north—almost 120 miles north. He was seen near Fish Lake Reservoir, a high-alpine lake on the Fishlake National Forest in southern Sevier County, and again north of there in Sanpete County, which borders on the Wasatch Front, the mountain playground for Salt Lake City. Gaunt and clean-shaven, he appeared on another security camera, this time at night, waving his arms to feel out an alarm; he broke in, but took nothing. Then, in November, an elk hunter reported seeing Knapp in Sevier County. That sighting mustered a 40-officer cabin-to-cabin manhunt that again turned up goose eggs. What followed was a long, cold winter of no news until the horn-hunting Fullers encountered the Mountain Man on the Dairy Trail.

KNAPP IS LUCKY HE WASN’T GUNNED DOWN in the shadow of the Wasatch Plateau when he opened fire at the helicopter, an outcome detective Conover attributes to “dumb luck.”

Shooting at a law-enforcement helicopter certainly amplified his woes. Now, in addition to the six felonies and five misdemeanors he was charged with on April 4 in Sanpete County—including assorted counts of burglary, theft, criminal mischief, and unauthorized use of a firearm—he could face charges of assault on law-enforcement officers and discharging a weapon at an aircraft. “The cabin burglaries,” Wingert said, “will turn out to be the least of his worries.”

But Knapp seemed at peace with his capture. In wire photos he appeared relieved, even grinning slightly at times. He told deputies he was tired of the elements—that he was getting older and the winters were getting colder—and that he didn’t hate people, but he didn’t especially like them either. He mentioned Robin Hood by name, pointing out that he’d simply tapped resources—food, firewood, guns—that weren’t being used.

Sanpete County authorities got him a shower, a new striped jumpsuit, and some pizza, then got out the maps and let Knapp draw lines between all the places he’s been. When you haven’t talked to many people for nearly seven years, apparently it builds up. Knapp didn’t appear concerned about lawyering up; he sang to officers like a proud jailbird.

Troy James Knapp had a closet full of baggage, I know, and I wish he was more Robin Hood and less just hood. I wish he’d only left thank-you notes instead of threats, and never shat in a pan. But his capture last week made me a little sad. Utah needs, as the Grateful Dead song goes, its friends of the devil spending the night in a cave—or cabin—up in the hills.

Some of the lawmen who participated in the manhunt don’t think Knapp was trying to hit the chopper with his rifle—just deter it. Why do you say that, I asked detective Conover. Because that’s what he told us, he said. I get the sense that they enjoyed talking with the Mountain Man, too—that though he’d become southern Utah’s public enemy number one, part of them admired something in his pluck.

“It’s a good thing you got me when you did,” Knapp told the men on the ground. “I was gonna move tomorrow.”

��

Correspondent Jon Billman () is the author of the short-story collection When We Were Wolves. He has written about diamond mining, the Great Divide Race, and the search for Steve Fossett’s plane for �����ԹϺ���.