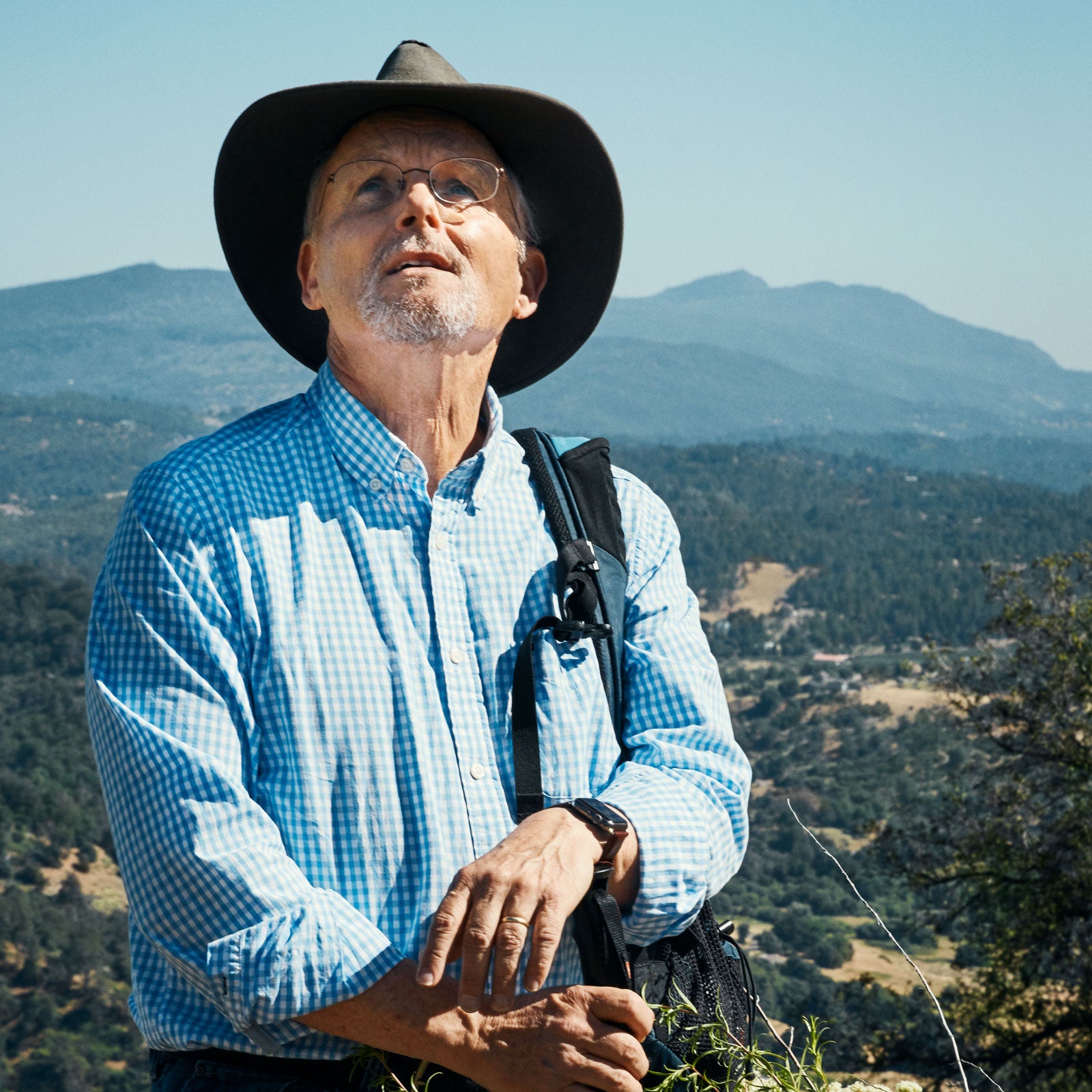

Several years ago, writer Richard Louv was on Alaska’s Kodiak Island to visit a remote lodge where his son worked as a guide. Walking from his cabin to dinner, he stopped briefly to double check that he had money in his wallet. A moment later, when Louv looked up, he was greeted by “two piercing eyes” watching him from a few feet away—a black fox. He and the fox stood frozen for a moment, locked in a staring contest. Louv eventually moved to continue his walk, but the fox followed along, disappearing back into the woods only when Louv arrived at the main lodge. “Today I recall few significant details about most of the people I met in that Alaskan camp,” Louv writes in the introduction to , his new book about communing with animals. “But the black fox’s eyes are still watching. I often wonder about the quality and mystery of that encounter.”

The 70-year-old Louv is best known as the author of , an unlikely 2005 bestseller that established the phrase nature-deficit disorder and is widely credited with helping spark an international movement to examine the therapeutic benefits of time spent outside. That movement is nearly ubiquitous today. New scientific papers revealing the power of wild places to counteract anxiety, stress, depression, ADHD, and even PTSD seem to make headlines every week. A unique segment of the travel market has recently sprouted up to deliver outdoor-starved Americans with curative doses of forest bathing and back-to-nature family bonding. Several nonprofits have been established to help facilitate research and expand public-park access and awareness, including one Louv cofounded, the . But back when Last Child debuted, Louv’s ideas were pretty radical. The book arrived two years before the iPhone, long before anyone was concerned with mobile-screen addiction or social-media-induced depression. “Americans around my age, baby boomers or older,” he wrote, “enjoyed a kind of free, natural play that seems, in the era of kid pagers, instant messaging, and Nintendo, like a quaint artifact.”

Speaking of quaint: Kid pagers? Which is to say, Louv proved himself a visionary, able to identify the collective blind spots we’ve developed amid the rah-rah spirit of our modern hyperdigitized lifestyles. We should probably hear him out, then, even if his latest passion, preaching about the power and importance of human-animal interactions, can come across as, well, a little New Agey and mystical.

Our Wild Calling began as Louv’s attempt to explain his encounter with the fox. “The genesis of this book is to try to understand that,” Louv tells me, speaking on the phone from his home outside San Diego, where he lives with his wife and entertains visits from a growing list of neighborhood creatures. “That elemental relationship, almost primal, indescribable, beyond language—a relationship we have with other animals.” But as he started investigating, the book’s mission evolved into something much larger. Louv contends that developing relationships with other species, both wild animals and pets, can not only provide similar benefits to time spent in nature, it may eventually become a key tool for battling mental-health issues.

As with his previous books, Louv turns to scientists for help backing up his thesis. The most compelling evidence he finds supports the importance of having pets. An emerging body of research shows that companion handle stress, depression, dementia, and many other issues. Louv also examines the in the U.S., which he writes has recently eclipsed household growth, and makes a strong case that the trend is linked to human loneliness, an epidemic that some experts predict will soon surpass the health impacts of obesity.

Louv is a big fan of pets (in one chapter, recounting his childhood, he posits that his beloved dog Banner taught him ethics), but his real goal is to convince us that cultivating relationships with wild animals can be just as therapeutic as curling up with a purring cat. Encounters like the one he had with the fox, he argues, have the potential to alleviate our increasing isolation as a species, and the fact that more animals are colonizing urban areas and living among us presents an opportunity to seek out new ways to relate with them. “I think that we are desperate not to feel alone in the universe,” he says. “And ironically, we are surrounded by a neighborhood of animals.” He envisions a collection of local Neighborhood Wildlife Watch groups, organized to share information and photos and educate residents about the beasts in their backyards.

This is a tricky sell. There’s little concrete evidence supporting the idea that, say, making room for the raccoons on your garage roof or going birding is good for you. Wild animals in our cities and towns are still considered by many—often accurately—as a threat (bears, mountain lions) or a nuisance (skunks, mice). What’s more, few scientists have historically been willing to wade into the squishier subject matter of human-wildlife relationships, fearing being dismissed for anthropomorphism, or worse, labeled a quack. As ecologist and writer Carl Safina tells Louv, that fear has ruined the field of studying human-animal interactions. It wasn’t until the seventies that scientists even began researching animal emotions in earnest, and we still know much more about animal behavior than the ways animals feel or think or communicate. Louv does uncover some fascinating research on the potential for human-animal communication, but most of it exists in the realm of companion animals.

“I think that we are desperate not to feel alone in the universe,” Louv says. “And ironically, we are surrounded by a neighborhood of animals.”

If Louv seems unfazed by the lack of empirical evidence, perhaps it’s because he faced the same conundrum with Last Child in the Woods. When that book was published, he says, there were only about 60 studies on the impact of time spent in nature; today there are well over 900. Any holes in his grand theories, he seems to argue, will eventually be filled by emerging science. And what we do know is quite promising. In 2014, a research team from Ohio State University repeated a decades-old survey about Americans’ attitudes toward nature. Its findings suggested that despite our increased separation from wild animals, we’ve become significantly more concerned about their welfare than we were in the late seventies, when the original survey was conducted. A British study, meanwhile, found that when people interacted with wildlife in their local parks, their psychological well-being improved.

As Louv might contend, we don’t necessarily need proof for such findings. On some intuitive level, we all knew that immersing ourselves in nature was a good thing. Why should it be a greater leap to believe that exposure to wildlife is similarly beneficial? In the book, each time Louv meets with a new source, he often brings up people’s unusual encounters with animals, then asks, “Have you ever experienced anything similar?” Almost all of them, even career scientists initially reluctant to delve into the esoteric, eventually share a wild story—an unlikely relationship with a swan, a swim with an octopus, a standoff with a bear—that they say had a profound impact on their lives or career choices, even if they can’t quite find the words to explain it.

Indeed, after all of his research, Louv himself lacks a tidy explanation for his brief bonding session with the fox, but a recent experience confirmed one of his hypotheses. He was in the parking lot of the , a conservation group he works with in Southern California. The people he was with began trading mountain lion stories, getting more animated as they talked.

“Suddenly, I realized we were all talking about something outside of ourselves,” Louv says. “And there was no room for rumination. So I think that’s one of the things that happens when you have these encounters. And when we talk about them together, life gets better. At least that’s what I found.”