The epigraph of author��C. Pam Zhang’s stunning debut��novel ��reads:��“This land is not your land.” It’s an apt opening for a western adventure narrative��that raises critical questions about��the stories most people have been��told about America.��

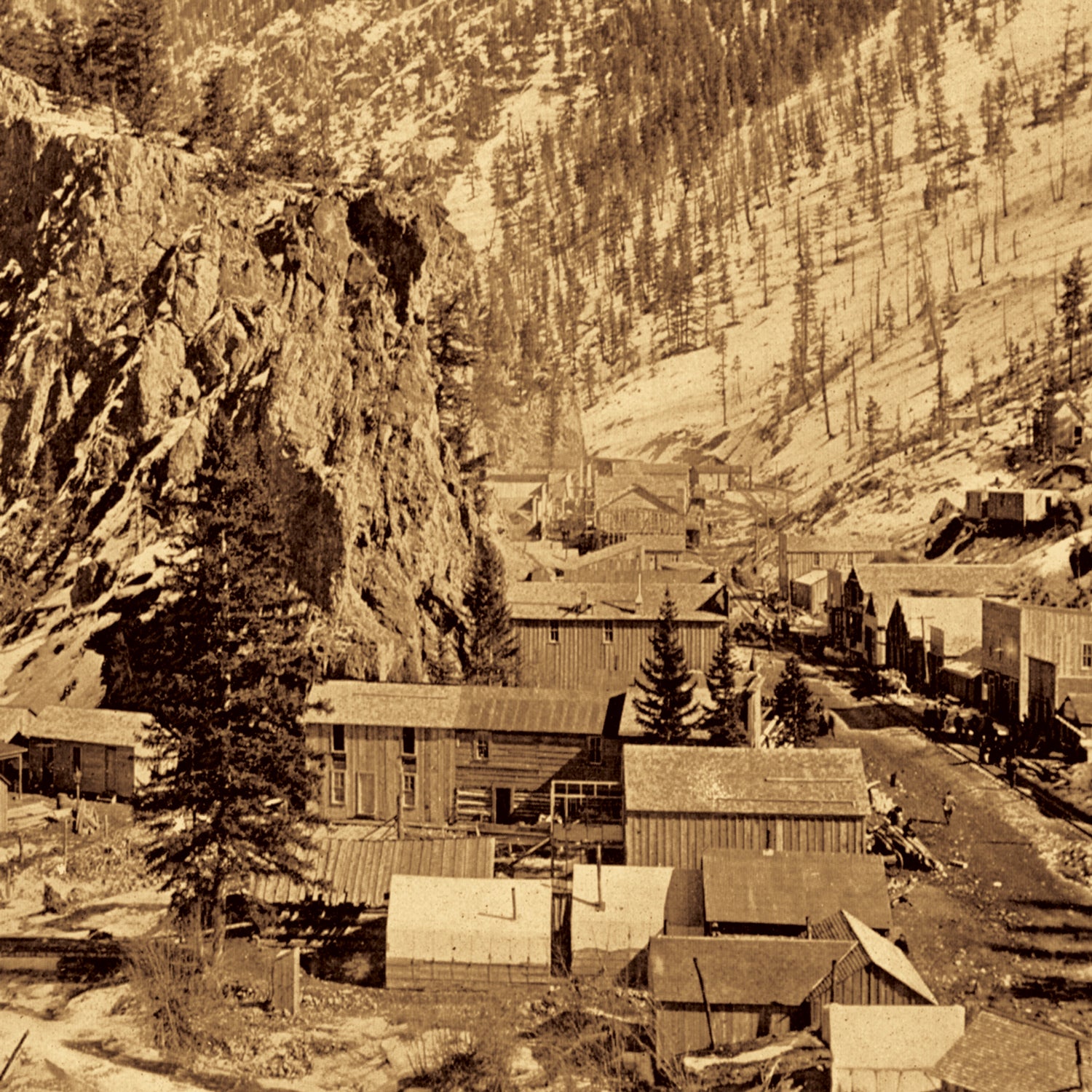

Zhang’s book,��out��April 7, is set in a fictionalized version of the West��during a��gold rush.��It’s��recognizable��but slightly altered: there are rumors of tigers, for example, and a lack of��specific��dates and geography that gives the setting a mythical quality. Still, this story has historical threads. Its central characters, Lucy and Sam (who are 12 and 11, respectively, at the beginning of the tale), are two Chinese girls living with their parents in a small shack. The lure of gold in the American West didn’t materialize as expected, so the family has scraped out a living through other mining work. But the harsh landscape is unfriendly toward homesteaders—and Lucy and Sam’s racist neighbors are unfriendly toward Chinese people.��

This should sound familiar.��Chinese immigrants were a central part of the��California gold rush, helping��build 19th-century��America. They worked in mines and forged��railroads across the West, where they were treated as second-class citizens. Those are ever present realities in Lucy and Sam’s story, but Zhang goes a step further, giving��their narrative a grandness and grit that has,��so often,��only been applied to white western frontiersmen.��

The story begins just after the death of the girls’ ba and the disappearance of their ma (who is presumed dead).��The��sisters��are faced with their first big quest: Lucy and Sam need to find three things to properly bury their father, according to their mother’s traditional instructions.��In what feels like a wink to the western��genre, the three items required��to complete the burial also happen to be things that are��notoriously scarce on the frontier: silver (two coins to place over the eyes), running water (to purify the body), and a home (a spirit will wander restlessly if the deceased��is not buried somewhere meaningful).

The burial process��leads the sisters far afield, and��as the book jumps forward and backward in time, they grapple with their understanding of home. This is the book’s central tension, and Zhang never suggests an easy answer. Lucy and Sam don’t feel welcome on American land because they are Chinese, yet��they were born here. They yearn for another place, but they can hardly imagine it. And, of course, there’s the fact that America is no one’s homeland except Native Americans’—and the��people of those nations are spoken about with disdain, fear, or indifference by most of the characters throughout the novel.

Zhang digs into these complications by bending the frontier narrative to the limbo that is the immigrant’s narrative. Sam, who��increasingly balks against a female gender role��as the book goes on, pursues a fearless path of adventure, falling in with mountain men and cowboys. At one point after the girls bury their father, Sam plants a foot on an animal’s skull and declares they’ll make their home there. “Sam doesn’t realize the image this calls up,” Lucy thinks, recalling her history books “filled with conquering men who stood��this way. Flags waved behind them in land emptied of buffalo.” Sam is always more sure of herself��than Lucy, and Sam wants to head��back across the ocean to the home they’ve always heard about. Lucy, on the other hand, initially values stability and civilization, parental approval, and an education. She often beats��herself up for not knowing exactly what she wants, which��Zhang��puts in deeply resonant terms early in the story: “In Lucy’s fondest dream, the one she doesn’t want to wake from, she braves no dragons and tigers. Finds no gold. She sees wonders from a distance, her face unnoticed in the crowd. When she walks down the long street that leads her home, no one pays her any mind at all.”

“The mountain man said that no man in this country could complete the railroad. He was right, after all.”

Moments like this are a heady pause in the middle of an expedition��that evokes so many elements of the western canon. Zhang easily inhabits some conventions of the genre, writing with poetic toughness about relentless bad luck and the visceral realities of survival. But How Much of These Hills Is Gold also rests on a foundation of the Chinese-American experience that’s so rarely represented in fiction about the West (or anywhere in American literature). The family eats salted meats and salted plums. They speak in the clipped sentences of frontier people while throwing in the occasional Chinese phrase, which Zhang normalizes by declining to italicize, translate the words, or provide heavy-handed context clues. It’s a long-overdue treatment of the American West, since��narratives about the frontier have had the tendency��to exclude many of those who helped build it.

Later in the story, when��Lucy’s��living in what Zhang would have us gather to be San Francisco, she watches Chinese workers��hammer in the last railroad tie. She sees a picture drawn up for the history books, in which nobody who participated in settling the West looks like her. She recalls the words of a white traveler she’d met once: “The mountain man said that no man in this country could complete the railroad. He was right, after all.”