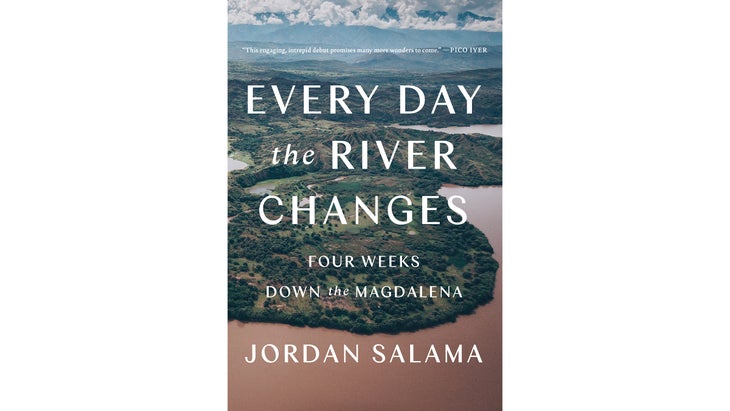

Every Day the River Changes is the December/January pick for the �����ԹϺ��� Book Club. You can learn more about the book club here, or join us on to discuss the book.

starts, as many good travel books do, with an ambitious idea. Author Jordan Salama, while studying as an undergraduate at Princeton, wants to travel the entire 950 miles of the Magdalena River, Colombia’s main waterway, in about four weeks. But Salama isn’t just being whimsical; he brings to this project a reporter’s eye, an environmentalist’s ethic, and a long family history of migration that enriches his approach to the narrative. The result is a thoughtful book that impresses with its sweeping history, evocative descriptions, and fascinating stories of people living along the river.

“To understand the river is to understand the country,” a woman in the beach town of Ladrilleros tells Salama on his first trip to Colombia, before his journey on the Magdalena, when he’s working in a Wildlife Conservation Society office for a summer. The river flows from the Andes to the Caribbean Sea, touching a diversity of environments and towns on its way. Salama points out its wide-reaching cultural importance, as a setting for Gabriel García Márquez’s novels, the inspiration for many myths and legends, and the birthplace of musical genres like vallenato and musical legends like Shakira. And of course, it’s changed dramatically alongside the economic, sociopolitical, and environmental shifts of the last century. Salama returns two years after his first trip to spend four weeks traveling the river’s length, sometimes by boat but usually by land, in order to spend time in the towns and villages along its shores. Along the way, he provides context around Colombia’s history stretching back to pre-colonial times, observations about current events like the increasing arrival of Venezuelan refugees and efforts to make the Magdalena fully navigable again, and enthusiastic descriptions of all the flora and fauna he sees.

But the book is not meant to be an authoritative take on Colombia’s history or geography. Instead, Salama brings readers along on not only his adventure but his evolving understanding of a country he still has much to learn about. In each place he stops, Salama seeks out the oldest people living there, who often tell him stories of witnessing a “golden age” of steamboat tourism and cargo transport in the early 20th century, which eventually ended due to environmental degradation and economic instability. Most everyone along the river’s banks has been affected by the armed conflict among the government, drug traffickers, paramilitaries, and various guerrilla groups that began in 1964. Salama says at the outset that his goal is to push back against the stereotype that the country is defined by such conflict: “Colombia is perhaps the most misunderstood country on earth,” he writes early in the book. Instead, Every Day the River Changes focuses on the ordinary people settled along a legendary river and the complexities of their everyday lives.

Tying all of this together seems like an impossible sell, no less for someone who had only been to Colombia once before and hadn’t done any professional travel journalism prior to writing the book (Every Day the River Changes started as Salama’s college thesis). Salama seems deeply aware of his limitations, writing, “Traveling in this way, and trading in stories, is inevitably a journey of selection—it was not lost on me that for each voice I heard, many others would be left out.” He frequently styles himself as a wide-eyed visitor who just feels lucky for the hospitality of the locals who show him around. These people propel the book. We meet a group of activists and biologists dealing with the invasive hippopotamuses introduced to the area by Pablo Escobar, a teacher who delivers books to children by donkey, a master jeweler, and a man who runs a floating restaurant in a town once bustling with river travel. Salama listens to locals speak about the changes they’ve seen over the years without much editorializing, but he often senses what’s been left unsaid. Watching men shovel sand to sell to cement factories at the mouth of the Magdalena, a man named Luis tells Salama it’s a “generational thing” for people to work on the river. Salama elaborates for the reader: “Their forefathers indeed worked on the river, but as fishermen and as boat captains. Now, the sons and grandsons were condemned to this far-less-glorious life of digging the very sand and sediment that both powered and destroyed their ancestors’ livelihoods just a century earlier.”

Salama acknowledges his naiveté as a visitor, but never abandons his quest for a deeper understanding of the place.

Salama, who is of Argentine, Syrian, and Iraqi Jewish descent, also weaves in his own family history to explain his own inclination to travel; some of his ancestors traded along the Silk Road, while his great-grandfather moved from Syria to Argentina and worked as a salesman on horseback. These asides elucidate Salama’s appreciation for the many paths of migration and mix of cultures that make Colombia what it is today. Recalling that many of his ancestors fled to Central and South America due to religious persecution, he writes, “It was not difficult for me… to picture my great-grandfather working as a traveling salesman by boat along the Río Magdalena instead of on horseback along the spine of the southern Andes.” It’s obvious how deeply his multifaceted family history and personal identity inform how Salama makes sense of his time in Colombia: he never leans on tidy narratives or confident diagnoses.

Every Day the River Changes also stands out as a travel book that pays homage to the joys of travelogues past. At one point, Salama references Ernesto Che Guevara’s memoir, , and it’s not hard to draw parallels to Salama’s own trajectory: “the young man in his twenties who set off wide-eyed on an anxious journey that would give him a new lens with which to view the world.” It seems that Salama understands his role as a burgeoning writer within a lineage that includes the likes of Guevara, Pico Iyer, and John McPhee (the latter two endorsed the book in promotional blurbs). Like McPhee, Salama is an insightful, fly-on-the-wall observer of the locals who make a place what it is; like Iyer, he’s interested in how his own multicultural background feeds his experiences abroad. He acknowledges his naiveté as a visitor, but never abandons his quest for a deeper understanding of the place. The resulting book is an engaging travelogue for the 21st century and a reminder that the best travel isn’t necessarily an epic adventure but a chance to hang out, getting to know new people—and yourself in the process. Echoing the sentiment of a well-known essay, Salama writes, “I’ve found that the more I travel to communities themselves out of the way and misunderstood, the more I’m forced to explain myself, over and over again, to different kinds of people I meet—and the better sense I’m able to make of my own identity once I’m back home.”