If Vincent Colliard were a smaller-minded person, he’d be a surf bum. That’s what his six-year-old self wanted to be. Growing up in a Paris suburb, Colliard kept a poster of surf legend Kelly Slater on his bedroom wall, and every day he’d stare wistfully at the sunkissed ocean-conqueror. One day, Colliard thought, that’ll be me.

He got his chance at eight, when his father left Reebok to work at Rip Curl, headquartered in the surf town of Biarritz, on France’s Atlantic coast. Colliard spent his after-school hours bobbing in saltwater and climbing the Pyrenees on weekends.

Then two things happened: at 16, Colliard read an adventure story about a polar explorer, who bumped Slater off his pedestal. And he discovered a fable about a hummingbird.

A forest fire had paralyzed all the animals with terror, but a tiny hummingbird kept filling its beak with water and dripping it onto the flames. “A few drops of water can’t save us all!” cried one despairing creature. “I know,” replied the hummingbird, “But I’ll do my part.”

So goes the poem by French environmentalist, who espoused a philosophy similar to that of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard: each of us must use the resources we’ve got to battle global problems. That might mean leveraging the wealth and clout of a big apparel company, or exerting one’s ability to pedal a bike instead of gassing a car.

The fable haunted Colliard. The more time he spent in the planet’s wildest places, the more he noticed a climate in crisis, and he wanted to do something about it.

Since 2006, when Colliard graduated from the French equivalent of high school, he’s been exploring the planet’s coldest places: he honed his polar travel skills in Svalbard, worked on fishing boats off Norway’s North Cape, logged his first solo expedition (at 21 years old) in Tierra del Fuego, and made two climbing trips to the Himalayas.

He still surfs. That’s how he met his girlfriend of eight years, Léa Brassy, who is an adventurer in her own right and serves as one of Patagonia’s surfing ambassadors. “I proposed we go on a surfing and skiing adventure in South Georgia,” Colliard said wryly. “I was too young and naive to truly understand the expense and logistics required for that kind of trip, so it never happened.” But in planning it, they ended up falling in love. “I didn’t get South Georgia,” he laughed, “but I did get her.”

Meeting his current expedition partner, Børge Ousland, required another stroke of youthful impetuosity. For four or five years, Colliard badgered the venerable Norwegian polar explorer with adoring e-mails, culminating in a bid to join his 2010 effort to circumnavigate the North Pole in a single season. “I said, ‘I can clean! I can take photos!’” Colliard recalled. Ousland agreed, and Colliard joined the team that encircled the pole in just 25 days—compared to three years for Roald Amundsen in 1906.

“It was a huge eye-opener for me,” said Colliard, who saw how the retreating Arctic ice let them travel at speeds that would’ve been impossible just 20 years ago. It struck him as tragic.

“A lot of people don’t like cold, icy places, but I thrive in those isolated environments,” Colliard explained. “I like to feel small and vulnerable, and to have the pressure of the environment on my shoulder,” he continued. Plus, the effort required to reach the planet’s icy poles results in a feeling of supreme reward. And adventuring for weeks on end gives him plenty of time for self-reflection. “Sitting in a silent tent, I am able to answer a lot of questions about my life,” he said. One such conclusion? The value of being the hummingbird.

The Icy �����ԹϺ���s of Vincent Colliard

Colliard and his “love and partner in crime” Lea Brassy often go on expedition together, like this 2014 trip to Iceland. “The idea was to go unsupported on a ski expedition looking for virgin waves to surf somewhere in Iceland. We camped in a traditional Scandinavian tent, a lavvu, in order to be able to store our equipment and dry the wetsuits.”

Colliard and Borge crossing Alaska’s Stikine ice field in 2015. “It was one of the rare moments where we could ski next to each other without being roped up,” said Colliard.

“The first complete crossing of the 120-mile Stikine ice field in Alaska was one of my hardest expeditions,” recalled Colliard. “Towards the end of the expedition, we were rationing our food and it became hard to sleep. We couldn’t escape the glacier and we were almost calling for help. I am very proud that Borge and I went through this expedition together as a team, and that we came back alive from that treacherous glacier.”

After nearly 3 weeks of “battle on the ice” during the 2015 Stikine expedition, Colliard was “hungry and exhausted” and happy to be back in the world of trees and colors.

After 23 unsupported days spent crossing the Chugach ice field in Alaska, Colliard and Borge Ousland head back to civilization. “This journey took us outside of our comfort zones,” said Colliard. “We asked each other ‘Are we in control of what we’re doing?’ That question lingered the entire expedition. One day, Borge fell into a crevasse twice. We are now stronger than ever. The Icelegacy project can only move forward if it is pushed by human power first.”

“I love the feeling of being vulnerable in the middle of the wilderness and trying to be part of it, basically like an animal,” said Colliard.

In 2016 Colliard crossed the 270-mile St. Elias icecap in Alaska. “Life on expedition isn’t always about struggling,” he said. “This picture was taken at the exit of the icecap. The lake in the front of the ice edge was partially frozen. We managed to find a way zig zagging in the middle of this ice paradise.”

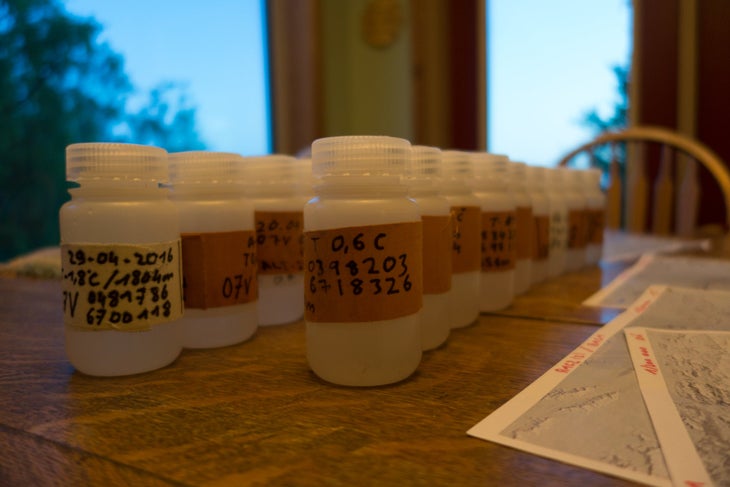

Colliard collects ice samples on his expeditions and them to a professor at the University of Anchorage, who studies the water isotopes to glean information about weather patterns and the acceleration of climate change.

“To me, the ice and the glaciers are a unique playground where I feel alive. I like how they challenge me,” said Colliard. “But they have no voice, they are fragile and dramatically receding. Not only does the ice melt, but the ecosystem around it is affected. Living in the outdoors and connecting with the natural elements has taught me the importance of resource conservation.”

“�����ԹϺ��� is a constant desire that drives me forward,” said Colliard. “It is a way of understanding how vulnerable we are and that we are connected with the nature. It is by living intense magical moments in the wilderness that we realize how beautiful our planet is. I believe that we all have an adventurous instinct!”

When Ousland proposed the Ice Legacy project—with —Colliard didn’t want it to be “just a sports project,” he said. “It’s so important to explain to a broader audience that climate change is happening, and there is a part of it that we’re responsible for,” he said.

That is why the Ice Legacy effort, which began in 2014 with Svalbard’s Spitsbergen glacier, includes a data-collection component designed to feed climate science efforts underway in frontcountry labs. During the project’s second expedition, on the Wrangell-St. Elias ice cap in 2016, Colliard and Ousland collected samples of surface ice and delivered them to Dr. Jeffrey Welker of the University of Anchorage. His analysis sheds light on how weather patterns have changed over time, and whether the ice’s surface layer of black soot (which accelerates its melting) are generated by nature or humans.

“Our hope is that we can build a system to keep the ice frozen till it reaches the lab,” said Colliard. Melted samples are valuable, but examining ice under a microscope lets scientists see right down to the atom level.

The duo estimates they’ll need at least ten more years to complete all 20 ice-cap crossings (they’re currently completing the sixth, in Alaska’s Chugach range). In the meantime, they intend to share their stories through as many media channels as they can.

Mountain Hardwear will help: Colliard is one of the athletes the company has chosen to support through its Impact Initiative. Launched in October 2017, the Impact Initiative uses Mountain Hardwear’s social media channels to disseminate inspiring stories of activist/adventurers.

“I want to inspire people to do what they can, and to really question their habits of consumption,” Colliard said. “In the end, I care more about that than the expedition.”

It’s a surprising comment from a 31-year-old. Most of us need several more decades—if ever—before we’re able to move beyond the pursuit of personal glory. But perhaps Colliard simply packed a lifetime’s worth of outdoor adventure into his twenties. “I’ve been doing expeditions now for 13 years, and I have fed my ego enough to be happy,” he said.

Thus, he’s turning more of his trips into opportunities to educate the world about climate change. He and his girlfriend Brassy have agreed to film five documentary programs over the coming year with a German production company called Boekamp & Kriegsheim GmbH. The first episode, which focuses on melting glaciers, followed Colliard and Brassy from the glaciers (where they skied) to the sea (which they entered via rafts). The second installment will highlight sea level rise as the couple sails among tropical atolls (Brassy and Colliard divide their time between Biarritz and a small sailboat in French Polynesia).

He channels the hummingbird at home, too. He buys locally-grown food, rides a bicycle whenever he can, repairs his gear rather than replacing it with new, and buys carbon offsets for the long-haul flights his trips require. He’s also investigating the viability of replacing his car’s gasoline engine with a water engine. “Owning a boat means you’re always fixing something, so I know that a water engine would be a lot of work,” said Colliard, “but we will both feel so much better, to use alternative fuels.”

Will that be enough to save the wild places he loves? Maybe not, he conceded. But he’s dedicated to doing his part. “An ocean is formed by billions of drips,” he explained. “And if everyone did their drip, we can make real change.”