This story originally ran in the Summer 2020 issue of The Voice.

Who, exactly, should qualify for a pro deal in the outdoor industry? A ski patroller? Full-time mountain guide? Retail employee? Most everyone can agree that these professions get a green light. But how about a seasonal whitewater guide getting a deal on skis or a yoga instructor getting a discount on a tent—greenish yellow? How about someone who takes an avalanche safety course or an amateur photographer with a nature blog—red?

What about average enthusiasts who just claim they do one of the above?

Figuring out who deserves a steep gear discount is crucial to running a successful brand pro program. Connect with the right pros, the theory goes, and a manufacturer helps these influencers do their jobs, while also familiarizing them with the gear and driving full-price sales to local retailers for a win-win. But if standards loosen so much that practically anybody can stock up on gear for 40 percent off or more, then pro deals become something else entirely.

“Pro programs are a complete farce,” said Wes Allen, owner of Sunlight Sports in Cody, Wyoming. “The idea of a program where you discount to shop employees and people who work in the industry is a solid one. But anybody who’s being honest about it knows that the programs are completely out of control. It’s a way for brands to sell direct-to-consumer at a discount without violating their MAP [minimum advertised price] policy. And let’s be real, there are brands out there encouraging this behavior because they see it as an easy, high-margin sale.”

Without any industry-wide standards or watchdogs for pro programs, it’s tough to judge how well the system is really working. So we went digging for evidence.

The Broadening Definition of “Pro”

Employees at The Trail Head, an independent outdoor retailer in Missoula, Montana, run into shoppers with pro deals “every single day,” said owner Todd Frank. Sometimes they’re just showrooming—trying on boots and apparel in the store before heading off to order their gear directly from brands or on third-party pro platforms. Sometimes they’re attempting to use a prAna influencer card (good for direct purchases from prAna only) for a discount in the store, not understanding how the program works. Sometimes they’re getting their new pro-deal skis mounted.

“Over the last bunch of years, the number of skis we sell has dropped 15 to 30 percent a year, but the number we’re mounting has gone up,” noted Frank. “People are very open about [getting a pro deal]. It’s a badge of honor in a community like Missoula. It makes you a legit outdoor guy.”

“Legit” is exactly the point of contention. Who’s legit? Brands and retailers alike agree that true industry professionals deserve a gear hookup, noting that gigs like ski patrolling, guiding, and wildland firefighting often pay so poorly that these pros would struggle to buy needed equipment. Without pro deals, “there’s no way you could afford this stuff,” said Steve Kunnen, an avalanche forecaster, educator, and guide for Washington’s Mission Ridge Ski & Board Resort, the Northwest Mountain School, and the Northwest Avalanche Center. He considers his pro deals an essential part of his job: This past winter season alone he bought two pairs of Atomic skis and goggles, a Patagonia ski pack, and Arc’teryx shell pants, all at 40 percent off or more. “People don’t realize you hammer your gear” with daily, hard use, Kunnen said. “There’d be a lot more patches and duct tape without pro deals.”

And in the right hands, pros do serve as valuable influencers. “If a retail consumer sees a pro using a product, that’s a pretty big stamp of approval,” noted Derek Young, who manages the pro program for Sawyer Paddles and Oars.

Getting gear into the hands of specialty retailer employees can also pay off for outdoor stores: Not only is it a valuable perk for recruiting workers, but an enthusiastic recommendation from a shop clerk can drive sales. “All you have to do is walk into [a store] and meet an employee who’s like, ‘I was using this last weekend’—that’s hugely positive,” noted Gabe Maier, vice president of Grassroots Outdoor Alliance.

What some retailers do object to, however, is the extension of pro deals to the far margins of the outdoors, such part-time yoga teachers, students enrolled in AIARE avalanche courses, or “literally people who work in the parks department—not Yellowstone park, but tennis courts,” said Sunlight Sports’s Allen. Another gripe: Often, pro members are eligible for discounts well beyond their job categories, as in a backpacking guide also qualifying for ski boots. And some report concerns about straight-up fraud, with faux pros falsely claiming they deserve a deal. Young of Sawyer Paddles and Oars says applicants have sent him snapshots of themselves in a whitewater raft as proof that they’re professional guides.

Nobody in the industry tracks overall pro purchases, says Grassroots Public Relations and Policy Advisor Drew Simmons, but the organization has heard plenty of anecdotes from its member shops. “It’s an income stream [for brands] that’s based on promotional, off-price behavior,” Simmons said. “It seems to be broadening and growing at a significant pace.” (Several retailers say pro programs really started going off the rails about ten years ago.) Simmons added, “Retailers are understandably concerned that it has become such a significant part of many brands’ businesses that they will have a really hard time reining it in.”

And stores argue there’s much at stake when pro programs get bloated well beyond their original intention. “Everybody and their dog 85 has a pro form in a mountain town like ours, when they absolutely should not,” said Brendan Madigan, owner of Tahoe City, California’s Alpenglow Sports. “You’re effectively retraining the public to shop online always and first, and to look for discounts online, which makes them think brick-and-mortar stores are always more expensive. Brands are effectively undercutting retailers.”

“If a product that we sell is readily available from the vendor for 40 to 50 percent less, it makes us look really bad,” added The Trail Head’s Frank. “And it harms the vendors just as much, because they’re going to end up with nothing but a discounted sales channel.”

The Middlemen

You can’t talk pro deals—and their potential for abuse—without taking a hard look at third-party pro platforms like ExpertVoice, Outdoorly, Liberty Mountain, and Outdoor Prolink. These businesses partner with brands to manage their pro programs, in many cases vetting applicants, facilitating orders, and providing other services in exchange for a fee and/or a cut of each sale. (Another site, IPA Collective, approves applicants and then connects them directly to brand pro programs.)

Such programs maintain that they help vendors find and vet influencers, and also instruct their pros to send anyone who admires their gear to buy it at a local retailer. “The clear reason to have a pro program is to drive more full-price consumer sales,” said ExpertVoice CEO Tom Stockham. “It’s [about] finding the people who have the most credible influence with consumers, and making them better ambassadors for your brand.”

Reps for all platforms we questioned for this article (ExpertVoice, IPA Collective, and Outdoor Prolink) stressed they use strict protocols to evaluate applicants. “If you’re not careful with your pro program, you start to undermine your price point and extend discounts too broadly,” said Stockham, who adds that ExpertVoice uses anti-fraud software and cross checks with professional organizations’ databases to limit its members to true pros. A spokesperson for Outdoor Prolink noted that the company has five staffers who review the thousand-plus applications it receives weekly (90 percent are accepted, which the company chalks up to clear criteria on its website that weed out unqualified would-be applicants) and requires members to re-certify annually: “This ensures that 100 percent of our base [is made up of] vetted professionals.”

Retailers aren’t buying it. “The third-party sites are like drug dealers,” said Allen of Sunlight Sports. “They’re coming in with this story about how ‘we’re going to get influencers to push people to your retailers.’ That’s such a bunch of crap.” He argues that third-party shoppers don’t have any real connection to their local outdoor stores.

Frank adds that the sites’ business model encourages them to view applicants with a generous eye. “[Third-party sites] are making commission sales,” he said. “So they’re going to drive as much volume as possible, because that’s the only way it works.”

What’s more, some retailers say their vendors are on board with such everybody-in policies. According to a member of the sales team who worked closely with Black Diamond’s pro program, left the company within the past year, and asked to remain anonymous, “Using ExpertVoice captures a broader audience and requires less in-house maintenance. Yes, ExpertVoice is too lax with who they approve for pro deals, which Black Diamond is acutely aware of. However, it is also a huge revenue driver for the brand.”

In response, the brand shared a statement acknowledging that the pro program isn’t perfect, but Black Diamond continues to improve its system. It also notes that the brand is a key player in an industry working group on pro sales, which meets to share notes on best practices, including dealing with abuses.

So what’s the truth behind becoming a pro? We went undercover to find out. In our investigation (see p. 87), the third-party platforms we applied to accepted our fake profiles more often than not. “If you’re willing to lie about who you are, it can be hard to catch someone like that,” noted ExpertVoice’s Stockham. “But it will happen, and you’ll be kicked off the platform forever. We will always want to work with retailers and others to figure out how to make the system work better.”

Some brands say they recognize the loopholes as well. “We are aware of some issues regarding pro/industry purchase sign-up validation and are taking aggressive steps to correct any problems around our internal approval process as well as those of our chosen partners to … tighten controls in a way that ensures a healthy program,” said Andy Burke, head of commercial sales at Outdoor Research.

Bro Deals—and Consequences

In some pro programs, membership comes with an extra perk: periodic discount codes meant to be shared with friends and family, aka the “bro deal.” Recent promotions from Patagonia and prAna have offered each of their pros three codes at 40 percent off to share—much to the chagrin of the retailer community (Patagonia’s codes were each good for up to $2,500 worth of gear).

“The question is, is a friends-and-family program really an extension of the pro purchase influencer program?” asked Grassroots’s Simmons. “Expanding accessibility to everyone you know—is that supporting the original idea [of a pro program], or is it a whole different area of revenue generation? Friends-and-family promotions seem like the number-one thing to train people to [wait for] a good deal every year.”

Besides, members of a pro’s social circle could otherwise be full-price customers—so why offer them deep discounts? According to prAna’s vice president of marketing, Jeff Haack, “We want to give [our influencers] an opportunity to share their love of the brand and products.” (No other brands we approached agreed to comment.)

But retailers suspect otherwise. Allen guesses these promos are a way to unload excess inventory, and Frank said, “Friends-and-family discounts are prolific because most of the companies are just using them to drive volume. We have a lot of publicly traded companies in the outdoor industry now, and they’re beholden to the board and the shareholders”—which means they’re under pressure to maximize profits every quarter by whatever means necessary.

Ultimately, such complaints about excessive pro deal activity can translate to concrete consequences for brands. Frank dropped Scarpa from The Trail Head last winter: “There are people who should not be getting deals from Scarpa who are getting deals every day. Consequently, I just can’t sell it.” (Scarpa did not reply to our requests for comment.) Allen has similarly scaled back business from several brands so far, and is “having super-hard conversations with” a few others (he declined to name which ones).

And Maier of Grassroots predicts that overly generous pro programs will backfire industrywide. “It seems like the programs were created to enhance brand loyalty,” he said. “But where the programs are now, all the anecdotal information points to creating price loyalty. Instead of building up brand equity, it’s having the opposite effect.”

Reining It In

Nobody tracks the precise number of pro program members across the industry— or what percent of total purchases they account for—but our investigation shows how easy it is for someone without real credentials to get access to a killer deal. So how can the industry dial back the free-for-all and restore pro programs to their original purpose?

The first, and likely most effective, step: tightening up the vetting process. “It would be a huge positive step to get some validation at all levels,” said Maier. “If these programs are truly intended to be there for influencers or people who are connected at retail, then what’s the harm in doing a little more work in verifying who’s accepted?” Despite assurances from program managers that all applicants must pass strict scrutiny, our undercover investigation proves otherwise: In some cases, fake pros were granted almost instant access using fake credentials.

Instead, managers could require additional documentation if something in an application looks fishy—such as professional certifications or, for retail employees, the store’s invoice number—or even call someone’s claimed employer to double-check. Another safeguard for retail employees: Mandate that all purchases be shipped to the store, as Patagonia does. The best-run pro programs also require members to recertify every year, Maier says, so former pros can’t hang on to their discounts.

And, “if there’s not a direct connection to the local retailer, it doesn’t work,” said Frank. Many programs do include a note in their acceptance email about sending anyone who admires the gear to their local outdoor shop to make purchases, but there’s currently no guarantee that members even know which shops carry the products. Young of Sawyer Paddles and Oars says he asks his qualifying pros to send curious clients to specific local shops: “I’m trying to build that bridge between the pros and the retailers. Retailers have to trust that manufacturers aren’t abusing that discounted sales channel.” He even suggests taking the connection a step further: “Maybe it’s time for retailers to vet who’s qualified for programs.”

Wrestling these pro programs back down to size, of course, depends on vendors and third parties actually wanting to limit pro deal purchases—not intentionally treating them as a lucrative discount DTC channel, as some retailers contend they do. The current state of pro programs “isn’t a misunderstanding,” said Allen. “It’s not people making a mistake in executing pro deal programs. This is a calculated business practice that people are being dishonest about.”

Patagonia is one brand heeding its dealers’ calls for overall reform by embarking on a revamp of its own program. Among other steps, the company is reviewing pro categories and individual members and scrubbing those not deemed to match a stricter set of criteria, plus ending its twice-yearly friends-and-family promotions.

“We know we can have a deeper connection with fewer pros … that supports our business in a better way,” noted Patagonia’s Bruce Old, VP of global business, and John Collins, leader of global sales teams, in a statement to The Voice. “We also realize there are too many access points for discounted products in the market.” The fact that the brand is investing in more environmentally and socially responsible—and expensive—production practices, they add, helps make its full-price business even more important.

These kinds of brand-led reforms—essentially, hiring tougher bouncers for the pro deal club—are likely key to reducing abuses and maintaining a more exclusive definition of “pro.” After all, when everybody’s a pro, then really, nobody is. And that renders a pro program essentially meaningless.

Getting In: An Undercover Investigation

Just how tough—or easy—is it to get into a pro program? We went undercover to find out.

Most brands and third-party platforms say their pro programs are for true outdoor industry professionals only, and that applicants are carefully vetted to ensure only the deserving get in. Not everyone believes it.

Industry insiders report concerns about several types of objectionable “pros.” There are the applicants with questionable outdoor credentials— part-time guides, one-time NOLS students, etc. There are straight-up liars posing as legit pros. And some retailers even charge that platforms will accept absurd applications that are obviously frauds (The Trail Head’s Todd Frank successfully applied to ExpertVoice as President James Madison).

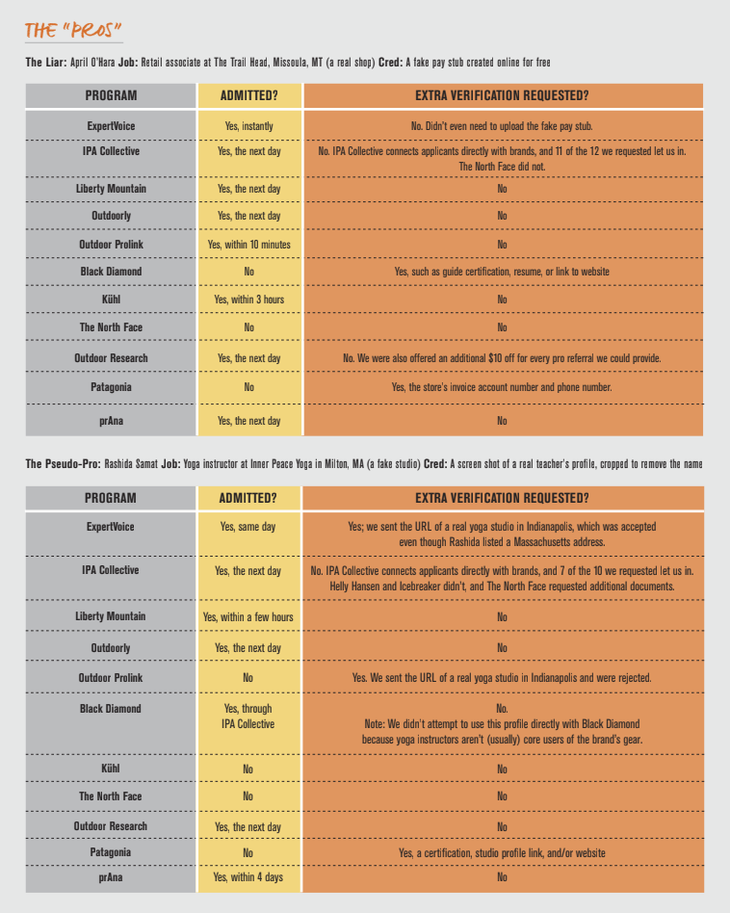

We tested the system ourselves with three fake personas, complete with bogus credentials, designed to probe brands’ defenses against those concerns. “April O’Hara” posed as a retail employee using a free, fake pay stub created online. Yoga instructor “Rashida Samat” submitted a screen shot of a real teacher’s online profile that didn’t include a name. And for our most ridiculous attempt, “Minnie Mouse” applied with a photo of a coffee shop punch card. We tried 11 pro programs (five third-party pro platforms and six brands directly). When admitted, we placed an order and, in all cases, received the gear (items will be donated).

In some cases, our applicants received a green light within a few minutes, suggesting no vetting process or a very limited automated one. In others, someone reviewed the application, but didn’t probe deeply into our supporting documents. Andy Marker, founder and principal of IPA Collective, who approved our application for “Rashida Samat,” noted, “I saw the [online studio] profile, and on that day, it was good enough for me.”

Ten of the 11 targets rejected Minnie Mouse (Liberty Mountain accepted her without question). But the results were mixed for April and Rashida.