THERE IS A MOMENT, rounding a bend in the highway that links Sarajevo to the small, mostly Muslim hamlet of Visoko, when the humongous, four-sided mound of earth that may or may not be the largest and oldest pyramid ever constructed first peeks over the horizon. Upon seeing it, there are two reasonable reactions. First: “Holy crap, how big is that thing?” And then: “How is it possible that no one discovered it sooner?”

Archaeologists Fantasy

Love Triangle Map

The answer to question one is approximately 700 feet, about a third taller than Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza. The answer to question two is a little complicated.

Until recently, the sleepy town of Visoko was known, if at all, as the home of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s largest leather-goods factory, and the symmetrical, forested hill called Visocica that looms over it was merely a picturesque backdrop. In April 2005, a Houston-based Bosnian expatriate and self-described amateur archaeologist named Semir Osmanagic visited Visoko at the invitation of the local museum director, Senad Hodovic. Osmanagic, 46, had come to see the ruins of a 14th-century castle that once sat atop the hill. As he stood peering out across the valley, he noticed another hill nearby that, strangely, was also shaped like a pyramid.

At that instant he experienced a flash of inspiration, a moment when “his mission in life” suddenly became clear. He turned to Hodovic and made a startling statement: “Professor, did you know that we are standing on top of the Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun, and the hill across the valley is the Bosnian Pyramid of the Moon?”

Osmanagic walked to his car and brought back a book he’d recently written about the Maya pyramids. He opened it to page 108, which showed a photograph of the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacán, Mexico, and held it out at arm’s length. “Clearly the shape and design of both pyramids are the same,” he told Hodovic.

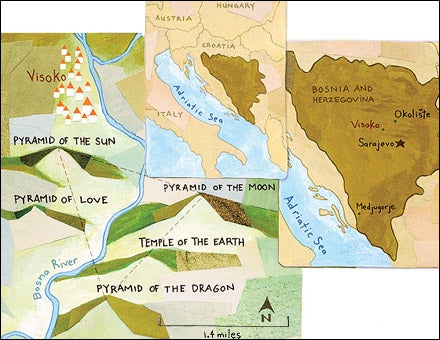

It wasn’t long before Osmanagic christened three other nearby hills: the Pyramid of the Dragon, the Pyramid of Love, and the Temple of the Earth. Six months later, he was overseeing the launch of a massive archaeological dig. He and a crew of locals uncovered what Osmanagic claimed were stone terraces encircling the pyramids, rectangular megaliths that sheathed them, and a network of tunnels leading right into the heart of the Pyramid of the Sun. The excavation has turned the little town of 17,000 into a tourist pilgrimage site and an archaeological carnival. Hundreds of residents have since picked up shovels. Thousands of volunteers and tourists have flocked in from around the globe to see the “Bosnian wonder.”

But this is not a simple story about archaeology. It can’t be, since every serious scientist will tell you that the “pyramids” of Visoko are nothing more than oddly shaped hills, the product of tectonic uplift. There’s no debate about this among the archaeological establishment. Which means this phenomenon is about something else: how one man’s wacky New Age vision grew into a collective national fantasy.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, where walls are still pockmarked with bullet holes from the wars of the nineties and hatred still festers among Roman Catholic Croats, Orthodox Serbs, and Bosnian Muslims (or Bosniaks, as they now call themselves), the sudden discovery of ancient, mystical structures in the Muslim north has been embraced as a divine gift. Though their land is still littered with land mines, Bosnian Muslims now have their own Machu Picchu.

Yeah, maybe the pyramids are more like Atlantisa glorious pipe dreambut that hasn’t stopped them from becoming a source of great pride. The Bosnian media has feted Osmanagic as a hero and publishes breathless updates on the dig. A flood of government grants and corporate donations has underwritten the budget, roughly $500,000 in 2006. Bosnian radio buzzes with hip-hop and turbofolk songs about the “find”; Osmanagic has even appeared in a music video.

In Visoko, many residents are creating guest rooms for tourists in their homes. The biggest and swankiest hotel in town recently changed its name from the Hollywood Motel to the Pyramid of the Sun Motel. (It has not taken down the caricatures of Eddie Murphy and Steven Tyler in the lobby.) Down the street, Pyramid Pizza cooks triangular pies, while pyramid-shaped key chains, coin banks, and bottles of pear brandy are as ubiquitous as Turkish coffee sets in the old market.

“This is the first good news coming out of Bosnia in a long time,” Osmanagic likes to say in his self-assured drawl. Last fall, the Web site for Pyramid Travel, the new Bosnian arm of a Swedish tour company, succinctly summed it up with what’s become a national mantra: “This discovery symbolically represents light in the end of the tunnel.”

I FIRST MEET OSMANAGIC on a warm morning in September 2006 at an outdoor café in the center of Visoko. The Sarajevo press has dubbed him the “Bosnian Indiana Jones,” an identity he both scoffs at and cultivates. Today, he’s wearing a collared white shirt unbuttoned to his navel and a flat-brimmed fedorajust like Harrison Ford’s.

Osmanagic pulls out a topo map of the valley and lays it on the table between us. “See, the three largest hills form an equilateral triangle,” he says, gesturing with the back of his hand. “And each side is perfectly aligned with east, south, north, and west. Most of the world’s major pyramids were built that way.”

He starts lecturing me about “geological anomalies.” According to a satellite thermal analysis he commissioned in the winter of 2005, the hills lose heat faster than the surrounding topography. He also deployed a ground-penetrating radar device whose images, he thinks, suggest that the Pyramid of the Sun is crisscrossed with passageways that meet at right angles. “Nature cannot make something like that,” he says.

Osmanagic drives me to the Pyramid of the Sun in a white Jeep Cherokee emblazoned with the logo of the Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, an organization he founded to broadcast the news and collect donations. In the backseat, wearing sunglasses, a safari vest, and beige leather shoes, sits Mohammed Ibrahim Aly, a 53-year-old professor of Egyptology from Cairo who has fallen under the pyramids’ spell. I ask Ibrahim Aly why so many scientists claim they’re just hills.”It’s jealousy,” he says. “Or they don’t know anything about archaeology. But I’d underline jealousy.”

Osmanagic cites small-mindedness from people threatened by the truth. “The trades like geology and archaeology will be the last to accept this, because it’s a revolution,” he says. “They’re afraid.”We park at the base of the hill, which has been converted into a sort of boardwalk lined with stands selling T-shirts with images of Osmanagic silhouetted against a backdrop of what appears to be a Maya pyramid. One shirt reads, FUCK THE COUNTRY THAT DOESN’T HAVE ITS OWN PYRAMIDS!

Up on the hill, there are several snack bars and roughly a hundred people milling about, a dozen of them with shovels. The ground is a patchwork of exposed rock and overturned soil. Some areas are roped off. In other places, people traipse right across the exposed megaliths.

We walk uphill for five minutes to a spot where scruffy diggers are scraping away at stone slabs. They put their tools down to gather around a three-foot-deep crack in one of the rocks, where a trio of local construction contractors in blue overalls is getting ready to deploy an industrial endoscopea semi-rigid hose outfitted with a camera on the tipthat could provide the first look directly inside the pyramid.

“As far as we know it’s not a chamber,” Osmanagic explains, “but the fact that it is so deep means it must be something.”

One guy revs up a portable generator, and the other two snake the camera into the crack. Osmanagic crouches to watch on a small black-and-white monitor. For the first couple of minutes, the screen is a hazy fuzz. And then my heart stops, and I’m pretty sure everyone else’s does, too. The hillside erupts in screams of “Semir! Semir!”

Some sort of inscription has come into focus. It’s a row of small circles and lines: It looks like writing. Osmanagic snaps a few photos with his camera and then makes a call on his cell phone. An E is clearly visible on the screen, then a D and then the rest of what I’m pretty sure is the brand name from an old pack of cigarettes. There’s a tremor of collective exhalation. Then the camera jiggles and the image is lost.

On the way back to the Jeep, one of the locals shows us a vein of stone running right through the middle of his snack bar. Osmanagic bends over to run his palm across the dirt. It’s nothing. “Just a crack,” he says.

Once we’re out of earshot, Osmanagic says, “Sometimes people see things that don’t represent anything. It’s OK. We’re raising awareness.”

“I WOULD SAY THERE ARE PROBABLY three types of people involved in the pyramids,” says Anthony Harding, professor of archaeology at the UK’s University of Exeter and president of the European Association of Archaeologists. “There are fanatics who want to believe this stuff, there are people who are being misled, and there are people who are leading people along, cynically, for political and financial reasons.”

Osmanagic seems like a true believer to me, but the four young Bosnian bloggers behind the AntiPyramid Web Ring prefer a different term: Pyramidiot. Other detractors point out that, prior to launching the Visoko dig, Osmanagic had spent 15 years exploring loopy theories of alternative history. He has written several books on fringe archaeology, including 2005’s World of the Maya, which ponders the idea that the Maya were descendants of aliens from the Pleiades star cluster. He told me he submitted a paper on the Maya as his Ph.D. thesis to the University of Sarajevo two years ago. He’s still waiting for the degree.

Osmanagic was born to a Croat mother and a Muslim father. He grew up in Sarajevo, where he earned two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s in international economics. Like many Bosnians with money, he fled the country in the early nineties, before the war. While Sarajevo burned, he built a lucrative metal-fabrication business in Houston that eventually had him overseeing 100 employees. His wife, Oksana, is a clerk; they have an 18-year-old son.

After his flash of insight atop Visocica in April 2005, Osmanagic started cutting checks to pay for some exploratory excavations, a PR manager, and, later, satellite and thermal analysis. (He says he’s contributed about $100,000 to the project to date.) Then, in January 2006, he launched the Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation Web site, which soon started indulging in a naughty habit: announcing project support from foreign archaeological authorities who either weren’t supportive or weren’t authorities. Royce Richards, an Australian archaeologist who’d e-mailed a simple query about the dig, found himself listed on the foundation’s “advisory committee of experts.” The same thing happened to Irish archaeologist Grace Fegan.

Last June, an Egyptian geologist named Aly Barakat vouched for the authenticity of the Pyramid of the Sun, claiming that he’d made the trip there on the recommendation of Zahi Hawass, the secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities and one of the leading pyramid experts. When Hawass heard this, he wrote an angry letter to Archaeology magazine, stating that he hadn’t sent Barakat, who “knows nothing about Egyptian pyramids,” and calling Osmanagic’s theories “purely hallucinatory . . . with no scientific backing.” That same month, 26 academics signed a petition to UNESCOwhich had announced plans to send investigatorsdenouncing the “pseudoarchaeological project.”

Despite the criticism, Osmanagic has gotten good international press, thanks to some rather lazy reporting. An early Associated Press article, which was broadcast by major news organizations all over the world, made the dig sound like a bona fide project and called Osmanagic an “archaeologist who studied the pyramids of Latin America for 15 years.” Last fall, I watched Osmanagic record a video statement from the safari-vested Ibrahim Aly”I don’t know yet if this is a pyramid. What I do know is the fact that this structure is man-made”that, by the end of the week, was moving on AP under the headline “Archaeologist Backs Dig at Bosnia Hills.”

When journalists visit Visoko, Osmanagic likes to show off the long stone terraces on the Pyramid of the Moon. Because the stones are cracked in roughly perpendicular lines, they do bear the superficial appearance of being man-made. But look closely and you notice that the “paving stones” are all different sizes. I ask Osmanagic why the ancient engineers who needed thousands of pavers hadn’t used one standard shape. “That’s how we would do it today, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best way,” he tells me. “They were a super-civilization. I’d like to have all the answers now. Unfortunately, I have much more questions.”

Serious scientists have no questions. Archaeologists note that Osmanagic hasn’t uncovered a single artifact and that his estimate that the pyramids are 12,000 years old7,000 years older than any other earthly pyramidcontradicts research showing that Bosnia at that time was just coming out of the last ice age and populated by a small number of hunters and gatherers. Geologists, meanwhile, say the angular, terraced hills around Visoko are merely the remains of a Miocene lake bed that was thrust upward by tectonic forces millions of years ago. Any interior passageways are likely old mining tunnels, though there’s no agreement on what the miners were after or when the shafts were created.

Osmanagic waves off the doubts. What he can’t understand, though, is why scientists are giving him such a hard time. “If you really believe there are no pyramids, then it should be in your interest to help this guy so that he can dig and find nothing,” he argues. “How can you disprove his hypothesis except through digging?”

FAIR ENOUGH, BUT YOU HAVE TO BE CAREFUL when digging for the truth. To professional archaeologists, Osmanagic’s methods seem like dental surgery with a chainsaw. No effort is being made to sift the dirt that’s been shoveled away, and parts of the stone sheathingthe outer skin of the alleged pyramidhave already been hacked to bits.

One of Osmanagic’s foremen is a burly local landowner in his late thirties who goes by the name Zombie. He wears military boots, walks with a stiff gait, and has a Boris Karloff face, all flat planes and angles, with two huge eyebrows that just about touch. His principal means of communicationand in this respect he is quite verboseis a wink that doesn’t fully close. He used to work in a meat factory.

“Whatever you see here, I found it,” Zombie tells me one afternoon at the Pyramid of the Sun. He’s been digging seven days a week for the past six months. I ask him how confident he is that he’s standing on a pyramid. “One million percent,” he says.

How can he be so sure? “It’s my ancestors,” he says. “They talk to me from inside the pyramid. If my heart is beating, I will work.” And then he sort of winks.

Zombie is one of roughly 50 locals who’ve scored a job on the project. With Visoko’s old leather factory operating at reduced capacity and unemployment in the region hovering around 40 percent, $20 a day to dig up pyramids isn’t a bad gig. Coal miners have been bused in. Osmanagic also estimates that some 5,000 volunteers contributed free labor last year, putting in upwards of 50,000 man-hours. They are a mix of Bosnian expats, archaeology geeks, and wigged-out New Agers. The weekend I was in town, I met two typical enthusiasts: Michelle Fröhlich, a 27-year-old masseuse and Pilates instructor, and Oswald Schwarz, an unemployed 28-year-old with a large Superman tattoo on his right shoulder. They rode a bus for 13 hours from Vienna and were put to work with garden trowels.We drive up the narrow, rocky road to the main dig site on the Pyramid of the Moon, with Zombie riding shotgun. Dozens of people who recognize Osmanagic give us a thumbs-up or wave or snap a photograph. We pass a traditional Bosnian house with a pyramid-shaped roof, which inspires Osmanagic to stop and point out the window. “See, it’s in our blood,” he says. Zombie turns and makes a triangular shape with his hands, in case I didn’t get it.

On the way down, Osmanagic stops to admire the Pyramid of the Sun in the distance. “From here you can clearly see the edges, where north and south meet,” he says. It’s true, the faces of the pyramid join at a sharp angle. But on the other side, it looks like there’s another hill abutting the back side of the pyramid. I ask Osmanagic about it.

“Yes, we think that there is a causeway leading up to the pyramid,” he says.

Everything, it seems, is evidence of the pyramids. “It’s not a question of whether the pyramids are there or not,” he says. “It’s a question of whether we’ll be able to uncover the pyramids or not.”

IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, so much ultimately comes back to who’s a Muslim, who’s a Croat, and who’s a Serb. When Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early nineties, animosities between these three groups exploded into a civil war that left some 200,000 dead and more than two million homeless. Today, the land is divided between the Serbian Republic and the Muslim-Croat Federation, which function like two independent states.

Osmanagic sees the pyramids as symbols that might help foster a common identity. “This is something that can unite people instead of dividing them,” he likes to say, and his grand plan is to turn Visoko into a national archaeological park. But the reality is that the dig might be just another stage in the conflict. Which is why, if you want to understand what’s happening in Visoko, you have to visit Medjugorje.

Twenty-six years ago, Medjugorje was a podunk town in the southern, mostly Croat half of Yugoslavia. That changed on June 24, 1981, when two teenage girls out hiking crossed paths with an apparition of the Virgin Mary cradling the baby Jesus. Shortly afterwards, they brought four of their friends along, the apparitions reappeared, and the Vision rush was on. Since then, some 20 million Catholic pilgrims have come to look at “Apparition Hill”a stampede that has become a major driver of the regional economy.

Given all that, it’s little wonder there’s an appetite for a Muslim miracle. A NATO officer who was visiting the pyramids and asked not to be identified put it to me this way: “Isn’t it obvious? The Muslims are trying to create their own Medjugorje. Why should the Croats get all the tourists?”That’s a cold assessment, but it explains why Bosnia’s Muslim politicians have been falling over themselves to support the project. Both major candidates for the Muslim slot in Bosnia’s three-seat presidency visited the site last summer. And the incumbent, Sulejman Tihic, personally pressed the case for the pyramids to the director-general of UNESCO, Koichiro Matsuura, at an international summit in Croatia last June.

Osmanagic vehemently disputes the notion that the dig is all about ethnic bragging rights, pointing out that he gave a presentation to the Catholic cardinal in Sarajevo, and claiming that official representatives from more than 30 countries have visited the site. Yet Muslim nations have shown the most interest, by far. Last July, former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad toured the dig with a group of investors to see how his country could help. (Osmanagic says Malaysian companies have donated nearly a third of the total budget, including roughly $220,000 from a single import-export company.) At a talk by Osmanagic in Zavidovici that I attended last September, the ambassador from Libya showed up, along with representatives from the Iranian, Egyptian, and Pakistani embassies. No other countries sent emissaries.

On my last morning in Visoko, I witness what feels like an example of outright political posturing at the Pyramid of the Moon when Vahid Heco, Bosnia’s minister of mining and energy, and Ferid Otajagic, the minister of urban planning, show up in fancy suits and sunglasses.

“We’ve come to see how we can help the foundation,” Heco announces to me, in front of a camera from a Bosnian TV network. “And we are going to help!”

I ask Heco to elaborate; he responds that the Pyramid of the Sun Foundation recently requested $52,000 from his ministry.

Will they get all that money?

“They will,” he says with a grin, then adds, “Very fast.”

WHILE THE MONEY the money flows into Visoko, the National Museum in Sarajevo languishes in disrepair and has to forgo heat in winter. There is not a single academic archaeology program in Bosnia, and there is just one prehistoric archaeologist, Zilka Kujundzic-Vejzagic.

Just a few miles from the pyramids, Kujundzic-Vejzagic is at work on a dig of her own in the tiny village of Okoliste. With funding from the German government, she is slowly uncovering what may be the biggest and best-preserved neolithic settlement ever discovered in Europe. Unlike the circus in Visoko, the project is proceeding at the rate of millimeters a day, without any fanfare.

When I call Kujundzic-Vejzagic for a comment about the pyramids, she says she’sweary of the topic but understands why people want to believe. “Look, we’re a small country that wants big things,” she sighs. “This is a political project, not an archaeological project.”She hands me over to her colleague Enver Imamovic, an archaeologist at the University of Sarajevo, who speaks more freely. “Osmanagic is a demagogue,” he says. “He thinks he is the messiah for our people, that he will bring El Dorado. It’s a tragedy, and it’s impossible to stop him, because all levels of government support him.”

Just about everyone in Visoko backs him, too, as I learn by asking around. An elderly woman I found sweeping the street in front of her house laughed at the very idea that the pyramids aren’t real. But her answer betrayed a hint of doubt. “If they don’t find the pyramid, we’re going to make it during the night,” she said. “But we’re not even thinking about that. There are pyramids and there will be pyramids.”

Another old woman came over to join the conversation, adding, “Semir is with us, and we are with him. When people talk about him, we should stand up out of respect.” As she said this, she patted the top of her head.

This worshipful attitude is likely to spread in the near future. While the dig was on hold during the brutal Balkan winter, Osmanagic was visiting Easter Island, Stonehenge, Machu Picchu, and other mystery spots with a film crew from Bosnia’s Federal TV network. The resulting 12-part series, to air this summer, aims to put the Visoko pyramids in context. It’s based on Osmanagic’s recent book, Civilizations That Existed Before Official History Began. Meanwhile, Osmanagic says he plans to open tunnels inside the Pyramid of the Sun to tourists in mid-April.

Eventually, though, the Visoko carnival will reach its inexorable conclusion. Since there are no pyramids, the dig can only go so deep before this realization sinks in. Osmanagic will board a plane back to Houston. The residents of Visoko will put down their shovels and go back to their renovated homes. And Bosnia will know one more disappointment.

But perhaps another outcome is possible. On one of my last days in town, I’m at the Pyramid of the Sun listening to Osmanagic deliver his practiced spiel to a group of NATO officers. I zone out and start paying attention to a distant worker in overalls hacking away at the mountain and dumping the dirt into a wheelbarrow. He is carving out a rectangular niche where one of the terraces of the imaginary pyramid meets a wall.

Suddenly it dawns on meand I’m shocked that it has taken me so long to figure this outthat Osmanagic is carving pyramids out of these pyramid-shaped hills. He’s digging where he expects to find the pyramids, but if the hills are made up of layers of fractured sandstone, he could find evidence anywhere he digs.

Psychologists have a word for this: pareidolia. It’s what happens when people see the Virgin Mary in a grilled cheese sandwich or Elvis in a sweat-stained T-shirt. We’re all hardwired to find patterns in the static of everyday life. It’s part of what makes us human. And, occasionally, this instinct gets carried to an absurd extreme.

The deeper Osmanagic digs and the more money is poured into the project and themore the mystique around the pyramids grows, the more everyone involved will be dependent on there actually being pyra-mids. There will be strong incentives not to dig too deep, to uncover just enough but not too much, to find but also not to findto discover something suspended between fiction and reality.