“Feel that?” Lance frowns, wild-eyed behind his ski goggles, his ponytail whipping in the wind.

Backcountry Skiing the French Alps

Brewer hits the down button on Bellecôte

Brewer hits the down button on BellecôteBackcountry Skiing the French Alps

Brewer on l'Aiguille de Peclet, hungry for more

Brewer on l'Aiguille de Peclet, hungry for moreMap

Backcountry Skiing the French Alps

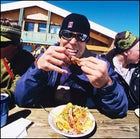

The author having a little rabbit at Les Deux Alpes

The author having a little rabbit at Les Deux Alpes“What?” I reply, aware of little but my own labored breathing here thousands of feet above the Alps’ highest ski area, Val Thorens.

“Static electricity!” Lance shouts, motioning at the skis A-framed above my backpack. “It’s moving between your skis. Listen and you can hear it buzz.” Already the April sky has blackened and started hurling lightning bolts at surrounding peaks. We’re clinging to boulders just below the summit of the 11,683-foot Aiguille de Peclet, hoping to clamber up the knife-edge ridge and drop the glacier on the other side. But not if it means playing moth to the hypercharged atmosphere’s bug zapper. The humming sounds like bacon frying.

Our partners, Lee and Beej, climb up to our perch. They’re followed by two Belgian snowboarders. After skinning for an hour, then booting up a face for 15 minutes, no one wants to do the prudent thing and turn back. One of the Belgians pulls a joint out of his parka and sparks it. “Care to schmoke?” he offers.

A pregnant pause elapses. The alpinists who normally haunt Peclet rigorously trained professionals from the International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations (IFMGA) and their clients wouldn’t dream of toking. Protocol must be considered here. That, and I need a few seconds to free my fingers from my glove. You know what they say: Quand les choses deviennent bizarres, les bizarres deviennent professionnels.

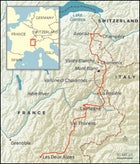

That’s the motto of our trip, a 15-day, 200-mile, three-nation (but mostly French), frequently off-piste, do-it-yourself ski trek across the highest reaches of the Alps. Carrying only skis and whatever fits into 55-liter backpacks, we’re crossing the original duchy of Savoy, one of France’s most mountainous regions (now chopped into two ��é�貹���ٱ�Գٲ�, Savoie and Haute-Savoie). Having taken a train to Grenoble, in southeast France, and crossed into Savoie from the apex of Les Deux Alpes resort, we’re headed gradually north, before we detour into Italy, then past Mont Blanc, to a finish line where Haute-Savoie meets Switzerland. Although short car rides will connect some dots, the trek will unspool mostly on snow.

And we’re not in Keystone anymore. Up high, we’ll encounter an unholy congress of ice and rock, with zero trees to aid navigation in frequent fogs. The 360-degree aspects found at most Euro resorts will mean sun-affected, often unstable snowpacks. (During 2005-06, avalanches killed 57 people in the French Alps alone.) This is why IFMGA pros who know the difference between hoarfrost and its psycho-killer cousin, windslab, not to mention wilderness-first-aid training and a few dialects are the only people legally qualified to guide on Europe’s glaciers.

But professional guides have flaws. Like charging a fee. And nagging. And not, uh, cherishing the moment. Better to spend resources on France’s Institut Géographique National maps, which don’t mooch for tips. The only mountain expert we’re looking to is Aspen’s late Hunter S. Thompson, who gave us our motto, Quand les choses Or, as he put it, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”

“TIME TO TAKE THE PIG for a walk,” Lance grunts, shouldering his porcine backpack. Our packs are so overstuffed, weighing 40 to 45 pounds each, that we had to ride in the baggage compartment on the train from Geneva to Grenoble. It’s day one, in Les Deux Alpes, our jumping-off point. L2A boasts all the bona fides of a French megaresort: thigh-meltingly big vertical (6,350 feet), stunningly tan and pretty brunettes, and cafeteria meat that looks like chicken yet is in fact rabbit. We hike 20 minutes over the Savoie border and into La Grave or, as the paranoid North Americans who felt they discovered the place in the early nineties once called it, Vallée X, home to Europe’s steepest, scariest slopes. With no village, disco, or ski patrol, it remains a cow-dung-scented burg with 7,000 vertical feet of mostly ungroomed, no-beginners terrain. Unfortunately, shade reaches La Grave hours before we do. Forgiving spring slush has flash-frozen into brittle coral. Skiing it turns our teeth into castanets.

But we’re accustomed to mountaineering’s drags. I’ve done all kinds of expeditions with my old friend Lee Cohen, our 50-year-old photographer, who’s been blitzing the steeps at Alta, Utah, for 30 years. Utah native B.J. “Beej” Brewer, 30, won the 2001 national telemark championship and is sponsored by Rossignol; he and I skied the Swiss Alps two years ago, and he’ll prove to be Lee’s favorite subject. And Lance McDonald, 45, works a nine-to-five job for the town government of Telluride, Colorado (where I live), but still nails big peaks aplenty, including a pioneeringdescent on Alaska’s University Peak in 2001.

��

What snow La Grave does have ends well short of the valley floor, and the last 90 minutes finds us sliding down a muddy service road. One slip sends me Rickey Hendersoning 30 feet down tractionless chocolate milkshake.

The next day we catch a pre-dawn ride with our chalet keeper to Valfroide, a summer shepherd village that’s bereft of life. No lifts rise from Valfroide, only the Alps. Climbing skins and crampons will propel us across a vast, rarely skied expanse and up, up, up to the 10,620-foot Aiguille d’Argentière.

Since the monstrosity of the peaks shields the rising sun, we move quickly at first over icy, nearly frictionless hardpack. After a lunch of baguette and chocolate, though, things get scary. We’re alone, preparing to climb hairy-steep boilerplate. We snap ski crampons onto our bindings for extra bite, but it’s extremely dicey. In some spots the surface is uneven; should the metal teeth of the crampon mistakenly bite air, there follows a sickening jerk downward.

After nine hours and 4,470 beastly feet of climbing, we finally reach the summit, wiggle into harnesses, and don helmets. The couloir splitting Argentière’s northeast face begins with a near-vertical chunk of mixed rock and snow; we’ll need to rappel in.

Hanging on the rope like a worm on a fishhook, I realize eight years have passed since I last did this. I’m the least experienced mountaineer on the trip. Which is kind of a good thing, like being the lousiest house in an upscale neighborhood: The others’ property values lift mine. With the capable Beej, Lance, and Lee around, I never want for a guide.

A porter, on the other hand, wouldn’t suck. Argentière is coated with perfect, fluffy snow, the kind backcountry addicts like us crave. But as we ski down, our behemoth packs blaspheme the glory of the powder, pushing our heads into recurring faceplants.

LATER THAT NIGHT, we push our faces into gooey raclettes. Kilograms of cheese still clog our intestines as we check in to the swank, four-star Hotel Fitz Roy, in Val Thorens. Compared with the spoiled brats of British families and the preening French trophy wives, we’re sadly underdressed. But the Fitz Roy treats us to pre-dinner champagne and cantaloupe wrapped in prosciutto. This gives us a nice, luxurious feeling that compels me to buy a $180 bottle of wine that �����ԹϺ��� will later refuse to cover.

Val Thorens is part of the megaresort called Les Trois Vallées, one of the biggest linked ski areas on the planet. Along with nearly 400 miles of groomed pistes, there are 184 cable cars, gondolas, and chairlifts. Stringing lifts up every conceivable ridge is France’s version of Manifest Destiny. Without this, ambitious interconnects like ours would be impossible.It takes us two days to cross the vast Trois Vallées: one with the Belgian snowboarders on the electric descent down Peclet, another through Méribel and Courchevel, where we see topless girls sunbathing on midslope rocks. At the bottom of Courchevel, the 184 lifts finally stop. This is an outrage. We’re forced to call a cab, which wants airfare money ($135!) to drive us 30 minutes to Champagny-en-Vanoise, where a tram connects to La Plagne ski area.”La Plagne,” explains a Frenchwoman with an impossibly alluring accent, “means The Place Where the Cows Go in the Summer.'” La Plagne is gigantic, spanning 24,700 acres and holding 50,000 beds. It’s two days after Easter, and the place is mobbed. The French hardly require something as momentous as Jesus’ resurrection to head to the hills. They’ll vacation if an earthworm grows its head back.

A disturbing number of them are sporting très passé purple-and-pink one-pieces, and three time travelers from 1992 board a quad lift with me. As is the habit of Euro skiers, they pull down the restraining bar without consulting me. The bar comes only halfway down, stopped by my pack. They fruitlessly yank it again. And again. “Je regrette,” I apologize, insincerely. They glare back and accept the situation only when they see how pointy my ice ax and crampons are.

The Place Where the Cows Go in the Summer is where the ski mountaineers go in spring. From La Plagne’s high point, we head toward a legendary 11,211-foot monster called Bellecôte. A series of uninterrupted 5,000-plus-foot descents spill down it, with incredible coffin-width couloirs and concave pitches. We spend 45 minutes skinning up the back side, then downclimb 200 feet of snow-coated rock poised above a void. Descending is an agonizing, one-limb-at-a-time ordeal: With crampons attached, we put an ice ax in one hand and a self-arrest pole in the other. Punch ice ax into wall, stretch leg down, kick till crampon bites, punch arrest pole, kick other leg. Try to keep the skis on your back from knocking an overhang. Try to trust the half-buried, UV-cooked fixed rope, the only thing keeping you from painting the rocks below with internal organs.The skiing should be the easy part. But first come fangs of rock and 600 feet of 45-degree steeps. Scratchy little hesitations what skiers call survival turns deliver us to a sun-softened apron. We let off the brakes and rip ginormous corn turns, floating our fat skis through water molecules, surfing as much as skiing.

ON DAY EIGHT, it becomes obvious that long underwear can be turned inside out only so many times before laundering becomes necessary. So we stop in Les Arcs, which connects to La Plagne via the Vanoise Express a behemoth $20 million, double-decker tram that moves 2,000 people per hour. Laundry for me means one SmartWool T-shirt, two long-sleeves, two pairs of long johns, a couple boxers, one pair of lightweight polyester pants, and two pairs of ski socks. If you’re going to spend a fortnight in the same socks, Europe’s the place: You can always blame the stench on the local cheeses.

The next day, we hitch a ride ten miles across the Isère River valley to La Rosière. Dark clouds hover overhead. The föhn, a notorious downslope Alpine wind, shoves chairs at lift towers. When I try to read a trail map, the föhn slaps it at my face. The föhn not only lifts temperatures and melts precious snow; Euros also blame it for illnesses ranging from migraines to psychosis.

The föhn blows.

But not in Italy. Once we cross the border, the wind backs off, as if it lacks jurisdiction. Trail signs and groomed tracks also stop abruptly. We’re suddenly in a gloomy outback, not quite sure where to go, headed for a lonely shelter.

��

Lee and I lag behind, basset hounds to Beej and Lance’s border collies. A friend in Montana says one way to cope in the mountains is to express the exact opposite of what you feel. So I tell Lee, “If we’re lucky, there’ll be more scary avalanche debris piles to cross. Plus a dozen more little creeks bisecting the trail.”

“Yeah,” he says, “it’s super-efficient to stop every tenth of a mile, take off our skis, and walk over them.”

“And let’s hope this trail stays a sidehill and never levels!” I add. “I like pushing constantly off one edge of my downhill ski. Gives me a nice Brian Boitano feeling.”

The sarcasm works for only so long. The route, through the Vallone di Chavannes, runs straight up to a high ridge. It never swerves, so the perspective never changes; it’s like jogging in Dallas.

Not till 8:30 do we reach the stone Rifugio Elisabetta. Built in the 1930s for summer climbers, it keeps a winter room open year-round. A “winter room” means camping, with a roof over your head. The only light comes from our headlamps beams crisscross and bounce off the walls, like strobes in the Unabomber’s private disco. A disco without music. More significantly, a disco without women. What a lame fucking disco this is.

ESTEEMED COLORADO alpinist Lou Dawson calls mountaineering “a social voyage thatcements friendships or reduces us to the raw basics of negotiation, leadership, and conflict.” Given our four competitive personalities, which find their full expression every night in vicious billiards games, friction is bound to happen, and it rears its head shortly after four o’clock on day 11, in a tiny Italian hamlet with the flatulent name of Purtud.

Lance and Beej, as is their hypercompetitive-skinny-guy wont, reach the bar first, and Lance orders two beers. When Lee and I arrive, expressing shock that Lance didn’t buy a round, he says, “I didn’t know you wanted one.”

“I didn’t know the sun rises in the east,” I say.

And what’s Beej’s deal? I know Lee wants him to “pop” on film, but all those greens and yellows? He looks fruity, like Sprite’s mythical “lymon.” As for Lee, who sports a writhing lip caterpillar, I refrain from telling him that Magnum, P.I. went off the air 20 years ago.

We’re headed back to France, approaching Western Europe’s highest peak, 15,771-foot Mont Blanc. Also, back to cheese that arrives in tartiflette, rather than a calzone the size of a cat. We manage to squish into the three-stage Funivie cable car without impaling an infant on an ice ax. At the apex, we get out and push through a beaten metal door painted with green, white, and red rectangles on one side, and blue, white, and red on the other: the flags of Italy and France, respectively.

With giant needles hovering all around us, we engage the world’s longest, most famous run: the Vallée Blanche, a glacier that courses between cliffs and seracs for 13.7 miles. To ski the Vallée Blanche is to swerve forever around crevasses and fallen novices, who flock here en masse despite their talent level. But, says Beej, “this is the best snow of the trip! This is sweet. Sweet cream.”

Most Vallée Blanche descents stop at Montenvers, where a train waits to trundle skiers the final 20 minutes to Chamonix. Between the glacier and the train, though, is a 280-step staircase, which is a fun place to watch scores of Euros simultaneously reconsider their pack-a-day cigarette habits.

The next day, we take a high-speed quad up Flégère, one of six ski hills around Chamonix, and then sweat our way up a frighteningly steep slope. From the ridge, skiers and snowboarders sporadically drop down, going right or left, but we charge straight ahead, milking elevation, skiing across more than down, till halted by a creek. Then a chug of water, reattachment of skins, and more of the chunka-ssss-chunka-ssss of our bindings hinging and skins greasing up across the snow. We soon reach a snowfield 200 feet below our objective: a humpy cornice atop another long ridge. Problem is, it’s hot, and we worry that tendrils of bonded snow will melt and drop a ten-ton chunk of cornice on our heads. Should we turn back? We should go for it.

We stretch out, 8,043 feet above sea level, with glorious views of Mont Blanc, Les Grandes Jorasses, and l’Aiguille Verte. In the distance, the shore of blue Lake Geneva sparkles. We snarf dark chocolate and snap photos. No wind blows. We plop our heads down and doze. “This is the most perfect place of all time,” Lee raves before conking out.

Later, we ski silky hero snow meandering to the right. For a moment we seem lost, but we gain a rollover and spot a cluster of barn buildings: Chalets d’Anterne, a popular summer stop for hikers. In April, it’s empty. After 13 days among the Alps’ teeming masses, we suddenly have an entire beautiful European valley to ourselves. Mon dieu.

OUR FINAL DAY finds us in Avoriaz, a collection of apartment blocks perched on the edge of a cliff. We grab an espresso and fries at an outdoor café as we switch out of well-used trail runners and into even riper ski boots. We’re now within Portes du Soleil, the globe’s largest international ski area, which straddles the Switzerland-France border not far from Geneva.

The border is our finish line, and our route to it is all in-bounds groomers. The last chairlift reminds me of all the others in France: skimpy. I never lose the sensation that my large New World ass is about to topple off. Crossing the 7,469-foot Pointe de Mossette, we hoot halfheartedly and raise our poles in triumph. We’ve crossed Savoy. There are no ticker-tape parades, no kisses from swell gals just the satisfaction of finishing a quest that involved 59 trams, gondolas, chairs, and drag-lifts and thousands upon thousands of vertical feet.

The beer in Champéry, our final stop, is cold and big and worthy. As I hoist one, my mind goes back to Peclet, with the static electricity and the Belgian snowboarders and the joint which, like most in Europe, contained mostly tobacco and did nothing but induce a cough.

With the sky short-circuiting all around us, our hair standing utterly on end, what exactly would a guide have done? One might hope that, at $400 a day, he’d have raised his ice ax high and acted as a lighting rod. But more likely he’d have anticipated the quickly closing storm and refused to attempt Peclet in the first place.

That would have been a bummer. Peclet’s west face is a 3,000-vertical-foot test piece guarded by seracs and riddled with crevasses. Authorities recommend crampons, a 30-meter rope, and to “avoid falling at all costs.” We inched around rock and onto a sketchy 45-degree face. Jammed our ice axes into the snowpack till steady. Anchored backpacks by looping straps over the ax heads. Hoped to hell our toeholds, on rime-crusted schist, were secure as we gingerly extracted our skis and lay them across the exposed fall line. Stabbed, with dental precision, boots into bindings. Slowly sheathed the ax and shouldered the pack, sensing how badly gravity wanted to suck gear and flesh down its maw. Exhaled nervously. Contemplated the dreary, foggy light below.

A pang of vertigo struck, then weirdness. The Belgian snowboarders, on a ridge above us, were trying to coax the sun out by singing. “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine ” Between us, Lee, Beej, Lance and I carried avalanche transceivers, cell phones, binoculars, ice screws, belay devices, headlamps, climbing skins, knives, and, if I’m not mistaken, some equine painkillers. We were ready for most anything. Except Belgian stoners atop a French peak crooning Louisiana’s Depression-era state song.

We were happy just to be traversing Savoy on our own power. Doing so removed our amateur status. When the going got weird, the weird turned pro.