Aspen Has Been Overrun by Zillionaires. Has the Town Lost Its Gonzo Soul?

The Colorado mountain town has always been famous for its steep skiing, epic powder, and hippies, oddballs, and celebs. But with changes like those of recent years, can a place stay weird?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The death of Bob Braudis, Pitkin CountyтАЩs six-term elected sheriff from 1985 until 2010, was no shock. He was only 77, but color had drained from his cheeks; he talked more slowly, breathing heavily between words; and he had begun walking with a cane. Bob was a friend, but not a tight friend. We exchanged emails over local columns I wrote, and usually talked at gatherings where we both happened to be. There was no apparent reason for feeling heartbroken, but when I heard the news I sighed deeply and rubbed my eyes to hold back tears. BobтАЩs memorial service drew hundreds to the Benedict Music Tent on the famous Aspen Institute campus. Nobody has that many close friends. Only those who create widespread connections attract such congregations.

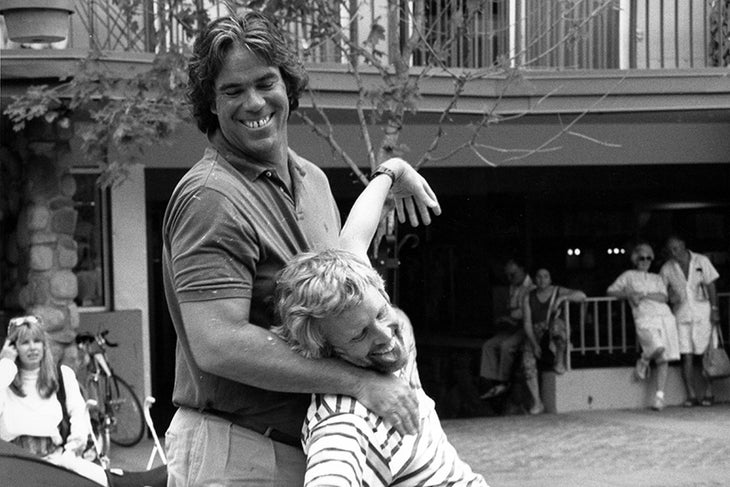

Bob, a long-haired, six-foot-six gentle giant, was the epitome of an Aspen character. Joe DiSalvo, his close friend and successor as sheriff, told me a story that captured BobтАЩs free, exuberant spirit, from years ago when ESPN was тАЬinterviewing AspenтАЭ to see if it was a worthy locale for the X-Games.

тАЬBob and I went to meet some ESPN suits at Highlands. One of the execs shook BobтАЩs gigantic hand. The exec asked, тАШGeez, whereтАЩd you get those hands?тАЩ Bob replied, тАШThey came with my dick.тАЩтАЭ Aspen has hosted the ESPN Winter X-Games for two decades running.

The sadness I felt was for certainly, but it was also over the loss of the wacky individualism he took from this world and, more acutely, the town. Bob was the latest on a long list of original Aspen characters now gone, from the truly famous, like John Denver and the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, to local oddballs like the serial letter-to-the-editor author Pete Luhn, who wrote almost daily, seemingly only to provoke fights with other readers, and lesser-known old-timers today immortalized by eponymous local landmarks. Puppy Smith Street is the namesake of Harold Smith, a career City of Aspen streets-department employee who once remarked to a couple of kids that the puppies they were selling for a dollar each were so ugly theyтАЩd have to pay him to take one, at which point they handed over a pup and a buck. No Problem Bridge is named for Joe Candreia, who was known for a front-yard junk collection next to his garden, where he claimed he could grow anything, тАЬno problem.тАЭ The ski run called FelipтАЩs Leap on Highland Bowl honors a local waiter, Henry Felip, who drove a 1948 WillyтАЩs Jeep Truck, electing to wear goggles instead of sunglasses, and took all dares to ski any mountain chute or kayak any section of a river, which ultimately resulted in his death on a stretch of whitewater rapids on the Crystal River called Meat Grinder during spring runoff.

Both DiSalvo and his former brother-in-law, Michael Buglione, who were in the midst of a heated sheriffтАЩs election, were at the memorial. While the two rivals appeared to be similar in their commitment to upholding AspenтАЩs historically progressive and humane approach to illegal drug useтАФwhich basically posits that adults can decide for themselves, we have to protect kids, and addicts shouldnтАЩt be put in jailтАФthe election was essentially about convincing voters who was most like Braudis. Also at BobтАЩs service was Mick Ireland, AspenтАЩs quixotic one-time-or-another mayor, reporter, county commissioner, attorney, distance runner, city councilperson, cyclist, and columnist. DiSalvo had somehow gotten crosswise with Ireland during the campaign, and the loss of his support was probably what would cost him the close election.

Slumped on my front porch that afternoon waiting out a thunderstorm, I wondered how the Aspen Times journalist Mary Eshbaugh Hayes would have viewed BraudisтАЩs passing. Renowned for her keen observations, Hayes covered Aspen society for 45 years, until her death at 86 in 2015. She wrote about everything without aiming to please anyone. She was an Aspen iconoclast who could distinguish between phonies and free spirits. Hayes could have told me what I really wanted to know: Is anyone coming to replace the characters Aspen is losing?