Paragliding British Columbia

Thanks in part to advances in wing technology, a few pioneering paragliders are smashing the limits by completing long-distance flights that were once thought impossible. Last spring, high-fliers Will Gadd and Gavin McClurg pulled off one of the most ambitious trips ever attempted: 385 miles down the jagged, frozen, potentially deadly spine of the Canadian Rockies.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

ItŌĆÖs shortly after five on the evening of August 1, 2014, and the winds on Mount Robson are calm, the sky is sapphire, and the sun is blazing, pushing temperatures to a near record 83 degrees. RobsonŌĆöat 12,972 feet the highest peak in the Canadian RockiesŌĆöis so far north that darkness wonŌĆÖt fall here for several hours.

Suddenly, a red streak flits past the summit. Next, an orange blip loops into view. TheyŌĆÖre paragliders, two of them, waltzing with the mountain, which looks like a Giza pyramid clad in ice. For nearly an hour, and soar like lazy raptors.

Climbers descending RobsonŌĆÖs south face stop to watch, dumbfounded. From above they can hear howls of joy. ŌĆ£Will was screaming the whole time,ŌĆØ McClurg, 43, tells me a few days later, while weŌĆÖre camped in a neighboring mountain range.

ŌĆ£I never thought it was possible,ŌĆØ says Gadd, 48, a renowned paraglider who has set several distance-flying records in the sport. HeŌĆÖs also an accomplished ice climber, having won almost every major competition there is. Gadd lives in Canmore, Alberta, and knows Robson well. ThatŌĆÖs because in 2002ŌĆöon his fifth attemptŌĆöhe completed the first one-day ascent of the peak. ŌĆ£I failed to summit Robson four times,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But flying paragliders over it? It had never been done or even seriously considered.ŌĆØ

Clouds usually shroud RobsonŌĆÖs glaciated flanks, while high winds often scream across its summit. ŌĆ£There are only about ten clear days a year up there,ŌĆØ Gadd says, adding that the area is just too remote, and the weather too volatile, for unpowered flight. This is the case throughout much of the Canadian Rockies, where almost nobody does long-distance paragliding. Roads and trails are scarce, making it virtually impossible to reach points high enough to launch from. As for landing, youŌĆÖll likely end up trapped in some far-flung, timber-choked valley. ŌĆ£You simply canŌĆÖt walk out,ŌĆØ Gadd says. ŌĆ£I know these mountains, and if you donŌĆÖt fly out, youŌĆÖll die back there.ŌĆØ

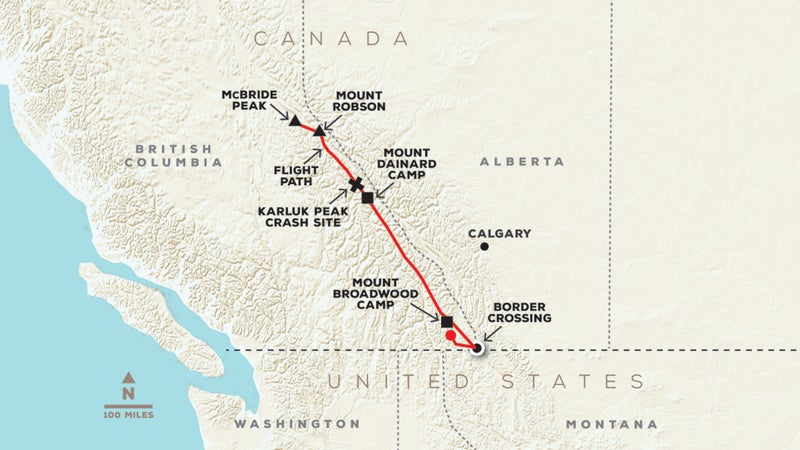

Despite the dangers, Gadd and McClurg set out last summer to paraglide down the spine of the Canadian Rockies, from McBride, British Columbia, south to the U.S. border in Montana, a distance of 385 miles. They christened their adventure the , a nod to the , a paragliding adventure race held every two years in Europe.

Gadd has competed in that event, but what the two are attempting in the Canadian Rockies is riskier. ŌĆ£The Alps are extremely accessible,ŌĆØ says veteran paraglider Bill Belcourt, vice president of the and director of research and development for Black Diamond Equipment. ŌĆ£There are no downsides to flying there. People live everywhere. Roads are everywhere. In Canada, you have much, much higher objective hazardsŌĆöthere are critters that can eat youŌĆöso you donŌĆÖt want to screw up.ŌĆØ

McClurg offers another perspective. ŌĆ£We are breaking the number-one rule you learn when you start paragliding, which is never fly over somewhere that you donŌĆÖt have a place to land,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Here, weŌĆÖre going hours without a place to land.ŌĆØ

McClurg lives in Sun Valley, Idaho, where he moved in 2012, fed up with life at sea after 13 years running yacht charters. (He has sailed around the world twice.) HeŌĆÖs also a former ski racer and an elite kayaker who has made Class V first descents in Central America. In 2003, McClurg took up paragliding and later embraced a style of the sport known as vol biv, from vol bivouac, a French phrase that roughly translates to ŌĆ£flight and sleep.ŌĆØ Pilots use specially designed packs they can wear in-flight, carrying tents, sleeping bags, clothing, food, stoves, and handheld avionics. During the day they soar; by night they sleep, wherever they happen to land.

In 2012, McClurg set off on his first vol biv expeditionŌĆö18 days and 500 milesŌĆöup the spine of the Sierra Nevada, from Southern California to the Oregon border. Along with two other pilots, he completed 13 flights, parts of which had never been done with a paraglider before. While not nearly as remote or technically difficult as the Canadian RockiesŌĆöthe terrain offered plenty of landing sites, and the pilots had vehicle support along most of the routeŌĆöit was an impressive accomplishment for a newbie.┬Ā

McClurg went for it again in 2013, hoping to fly from Hurricane Ridge, in southwest Utah, to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, a distance of some 500 miles. ŌĆ£But the weather killed us,ŌĆØ says McClurg. In the end, they eked out just 60 miles before calling it off. Shortly before the expedition, in July, while training near his home in Sun Valley, McClurg set the world record for the longest single foot-launched paragliding flightŌĆöseven hours and 240 miles, from Bald Mountain, Idaho, to just outside Helena, Montana.

A paraglider uses whatŌĆÖs called a wing, which is fashioned from high-tech fabrics. ItŌĆÖs shaped like a parabola, but with a flattened vertex (the top of the arc). Wings range in size, with the largest spanning about 30 feet. A paraglider gets lift the same way planes do: from pressure differences between air traveling over the top and bottom surfaces of the wing.

Today, most paragliders do what theyŌĆÖve always done: hitch a ride up a mountain to launch, soar for a few hours, and then glide to a predetermined landing spot. Flying long distances with a wing is a somewhat recent phenomenon, particularly when itŌĆÖs done for consecutive days or weeks at a time.

Russell Ogden, a test pilot for Ozone, a paraglider manufacturer whose innovations have revolutionized wings, told me, ŌĆ£Paragliding is a niche sport, and vol biv is a niche of that niche.ŌĆØ But vol biv, he says, ŌĆ£has become massive in the past ten years,ŌĆØ thanks to advances in performance. Many give credit for these advances to a French paraglider and naval architect named Luc Armant, who went to work for Ozone in 2008, joining its R&D team.

A typical wing is made of reinforced ripstop nylon and polyester, into which baffled chambers called cells have been sewn. To launch, a pilot slips into a harness and then runs forward while tugging on suspension lines to hoist the wing aloft. When air enters vents along the wingŌĆÖs leading edge, the cells puff up like a windsock in a stiff breeze and give the paraglider its shape.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It was a really scary, terrifying place to be,ŌĆØ McClurg says of a controlled crash he took on a mountainside. ŌĆ£It could have gone so much worse. I got really lucky.ŌĆØ

Three sets of suspension lines used to be standard. All those lines provided stability but also generated a significant amount of drag. Armant created a wing with just two line sets. To compensate for the loss of stability, he incorporated spaghetti-thin plastic fibersŌĆöliterally, weed-whacker lineŌĆöinto the baffled cells. Doing so dramatically cut drag, thereby increasing efficiency in the air, and it wasnŌĆÖt long before most other manufacturers started producing their own versions of the two-line wing. Nick Greece, an accomplished paraglider and editor of Hang Gliding and Paragliding magazine, says ArmantŌĆÖs design was a game changer. ŌĆ£Previously, we were doing 100-mile flights,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Now we were easily doing 160-mile flights, and then a 200-mile flight came next.ŌĆØ

Electronics are helping, too, especially bread-crumb trackers, made by companies like DeLorme and Spot. These handheld devices transmit position, speed, and altitude at regular intervalsŌĆötypically every ten minutesŌĆöto GPS satellites, which relay the data to the Internet, where a paragliderŌĆÖs route is viewable to anyone online. With trackers, pilots can instantly see where theyŌĆÖve been and where theyŌĆÖre going while airborne.

More than anything, though, vol biv is happening because Gadd and McClurg, along with a small cadre of like-minded pilots, are rewriting the rules of the sport.

ŌĆ£This trip will change the worldview of anyone paying attention to bivvy flying,ŌĆØ Bill Belcourt says. ŌĆ£All of a sudden, what you thought was daunting might seem not that bad. It changes your perspective. ItŌĆÖs like climbing with Alex Lowe. He had a way of making everything look a lot flatter.ŌĆØ

Gadd and McClurg planned the X-Rockies expedition over e-mail and by telephone. Practically strangers, they didnŌĆÖt meet face-to-face until just before their first day out, hiking together for an hour up one of the few trails decent enough to get them to their planned launch site at 6,788 feet. They were hauling 60-pound packs stuffed with supplies, their wings carefully folded inside.

When it was go time, at around 1 p.m., they unfurled their wings. They launched from a narrow alpine meadow perched barely above tree line, ŌĆ£with enough rocks and angle to make it technical,ŌĆØ Gadd recalls. The margin for error was zero. By 5 p.m., they were soaring around Mount Robson. During that historic flight, Gadd told himself, If we can fly over Robson, we can fly over anything.

They got two more days of good weatherŌĆöclear skies, light windsŌĆöbefore conditions swiftly deteriorated. Nearby wildfires spewed thick smoke, reducing visibility. Gusty winds and frequent thunderstorms forced them to detour into increasingly isolated terrain. By the end of day four they were separated. Gadd stayed above tree line and landed in a high meadow. McClurg struggled to reach him but couldnŌĆÖt gain altitude. With nowhere to set down safely, he crashed into the shoulder of Karluk Peak, slamming face-first into a rock.

I set out to catch up with them a few days later. On August 5, I fly into Calgary and rent an SUV at the airport. Over the next two days, I drive more than 350 miles with Jody MacDonald, who is on hand to photograph the expedition. SheŌĆÖs married to McClurg, and she was already a paraglider when they met in 2003. In fact, she gave him his first lesson.┬Ā

We head northwest, toward British Columbia. Gadd and McClurg are carrying an arsenal of technology, including satellite phones, VHF radios, and the bread-crumb trackers. I can obtain their tracker data with my iPhone. I can also type text messages into a website that relays them to their trackers. But none of this helps us get anywhere near them. They are simply too deep in the backcountryŌĆöat least 20 miles from the nearest road.

About 30 hours after we leave Calgary, near Revelstoke, B.C., I get a satellite text from McClurg: ŌĆ£Bring fresh underwear.ŌĆØ In the midst of circumnavigating peaks, crossing crevasse-riddled glaciers, and vaulting chasmal valleys, McClurg apparently needs a change of skivvies. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not unusual for him to shit his pants,ŌĆØ MacDonald informs me. SheŌĆÖs laughing, but sheŌĆÖs also serious.

Red Bull Media House is paying the costs of a big-budget, six-person film crew, which is trailing Gadd and McClurg in a helicopter for part of the expedition, dropping supplies while theyŌĆÖre at it. The crewŌĆÖs boss, Elizabeth Leilani of Reel Water Productions, manages to reach me during a brief period when my cell phone has coverage. ŌĆ£Come to Mica Creek,ŌĆØ she tells us. ŌĆ£The heli is there, and we can bump you up to the guys.ŌĆØ

I scour a topo map and locate Mica Creek at the northern frontier of B.C.ŌĆÖs Monashee Mountains. Six hours later IŌĆÖm in the heli, its blades thumping east. We head toward a cluster of glaciated peaksŌĆöcollectively known as the Continental RangeŌĆöscattered across a 25,000-square-mile wilderness that straddles the crest of the Canadian Rockies.

A thunderstorm is barreling toward us, spitting rain and sleet at our windscreen. The pilot, who had been chatting us up over the headsets, goes silent. He wrestles the heli through buffeting crosswinds and then points the nose toward a knife-edge ridge. Looking down I can see a meadow, perhaps an acre in size, wedged into a rocky nook. Two tents are visible: one is lime green, the other gold. The heli lands with a plunk. By now the storm is on top of us, a black fury of clouds and howling winds.

Clutching my backpack, I leap out. The pilot guns the throttle and roars off. McClurg emerges from the green tent, a little wobbly, and gives me a hug. He was asleep, snoozing on his bunched-up wing, and my arrival startled him. ThereŌĆÖs a dime-size scab on his upper lip and bloodstains on his wing. IŌĆÖve known McClurg since 2005, and every time I see him he looks like he just got back from a two-week beach vacationŌĆödeeply tanned, his tousled brown hair veined with sun-bleached highlights.┬Ā

By the time sunset arrives, the skies have cleared to reveal a buckled and contorted macrocosm of rock and ice extending to all horizons. We boil ramen, and I ask McClurg to recap his crash. ŌĆ£When Will and I got separated, I got into a bad hole and couldnŌĆÖt climb out,ŌĆØ he says. With daylight dwindling, he knew he had to get down. But where? He had already covered 20 miles and hadnŌĆÖt spotted a single clearing. A controlled crash into a mountainside was the only option.

ŌĆ£It was a really scary, terrifying place to be.ŌĆ” And thatŌĆÖs how I hit my face,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£It could have gone so much worse. I got really lucky.ŌĆØ He shook off the crash and scrambled to a ledge beneath 10,167-foot Karluk Peak to pitch camp. In the morning, desperate to find Gadd, he launched but quickly discovered that he didnŌĆÖt have enough lift to get over the next ridge. So he circled back and landed where he started. He tried again and finally achieved a successful flight. As McClurg would later record in his journal: ŌĆ£I was completely frazzled ŌĆ” dehydrated and low blood sugar, scared, knew I shouldnŌĆÖt be flying.ŌĆØ

McClurg headed south and found Gadd camped where we are now. Gadd spotted McClurg approaching and got on the radio to warn him away from landing. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs too on!ŌĆØ he yelled. ŌĆ£The conditions are just too strong!ŌĆØ

In mountains like this, whenever the sun is out, the ground heats up, radiating warm air, which rises into cylindrical columns called thermals. Fly into one and you get good lift, like stepping into an elevator heading toward the stratosphere. When a wing isnŌĆÖt inside a thermal, it descends. How fast it goes down is determined by its glide ratio, a measure of elevation loss to distance traveled. For paragliders, the ratio is typically 11 to 1, which means that if no other forces are acting on the wing, such as thermals or headwinds, it will fall 100 feet for every 1,100 feet of forward progress. If youŌĆÖre paragliding off a local hill and intend to land low, descending is not a concern, but it is in these mountains.

ŌĆ£Here, you do one glide for ten minutes and you end up on the dirt,ŌĆØ Gadd says. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like a samurai sword fight. There is no retreat.ŌĆØ

Thermals are usually indicated by the presence of cumulus clouds, which are created when moisture condenses as it hits the cool air at higher altitudes.

The clouds materialize above dominant topographic features, specifically ridges and summits, often aligning themselves like cotton balls in a conga line.

ŌĆ£We call those cloud streets,ŌĆØ McClurg says. Stay on a cloud street and you can leapfrog from thermal to thermal. But thermals donŌĆÖt always form where you want to go. Or they can become too strong, making high-alpine landings about as easy as swimming up a waterfall.

McClurg heeded GaddŌĆÖs advice and aimed for a nearby drainage. As he approached, his wing partially deflated, which is called a collapse. Seconds before plummeting into a stand of 50-foot-tall subalpine firs, he skidded into a narrow glade, only a short hike away from Gadd. ŌĆ£I was ecstatic to be back together again,ŌĆØ McClurg says.

Our camp, at 6,800 feet, is situated directly beneath the west wall of Mount Dainard, a 500-million-year-old marble-and-limestone slab that amplifies the thunder when squalls rip through. For three days the weather is spasmodic, alternating between rain, hail, lightning, wind, and sun. Gadd and McClurg hole up in their tents, usually napping.┬Ā

At first, McClurg was ready for a break, but after two days he canŌĆÖt sit still. If the sun is visible for more than 15 minutes, heŌĆÖs up, pacing, talking to himself. He holds out his arms, palms forward. ŌĆ£Feel that? Feel that?ŌĆØ ThereŌĆÖs a faint breeze blowing upslope, and heŌĆÖs sure this indicates developing thermals. Gadd emerges from his tent just as McClurg announces, ŌĆ£Dude, this is looking better.ŌĆØ

Gadd says, ŌĆ£I look at this as less worse.ŌĆØ

Gadd has auburn hair and a creamy complexion that seems incongruous with a guy whoŌĆÖs outdoors every waking minute. He started paragliding in 1992, when the sport was young and embraced mainly by climbers using wings as a quick way to get themselves off a peak. Ten years later he smashed the distance world record, by means of whatŌĆÖs known as a tow-launch flight, in which pilots are hoisted aloft with a winch and cable rig attached to the bed of a pickup truck. His flightŌĆöfrom Zapata, Texas, near the Mexican border, to OzonaŌĆöcovered 263 miles and lasted 10 hours and 38 minutes, a mark that wasnŌĆÖt beaten for a decade. ŌĆ£But equally important to me are the many firsts IŌĆÖve done,ŌĆØ he says. This includes a paragliding flight over Independence Pass in Colorado, as well as several new routes over the U.S. and Canadian Rockies.

Long before Gadd started paragliding, he was steeped in alpinism. His parents, who raised him in Calgary and Jasper, started taking him to the mountains when he was a toddler. Gadd is five foot eleven and lanky, with long, sinewy armsŌĆöideal tools for a world-champion ice climber.┬Ā

ŌĆ£Willie was on 5.6ŌĆÖs and 5.7ŌĆÖs by the time he was five,ŌĆØ his father, Ben Gadd, told me. ŌĆ£He is very connected with real-world adventures. He also just likes to show off. Since heŌĆÖs been really little, itŌĆÖs ŌĆśWatch me do this, watch me do that.ŌĆÖ HeŌĆÖs not the sort of guy who wants to climb all the 8,000-meter peaks. He wants to go to one and have a video running, because heŌĆÖs a performer as much as an athlete.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Like many alpinists whoŌĆÖve seen friends die or get injured while climbing and paragliding, Gadd has become adept at mitigating risk. In camp he entertains us with his favorite almost-got-killed tales. ThereŌĆÖs the time he was paragliding in Mexico and his wing spiraled so violently that G-forces caused him to black out momentarily. Or when he was paragliding near Boulder, Colorado, and hit a powerful wave of air that whisked him up to 18,000 feet in only minutes, the lack of oxygen temporarily blinding him. These mishaps have left Gadd with a pragmatistŌĆÖs instinct.

ŌĆ£Willie describes it as the power of negative thinking,ŌĆØ says his father. ItŌĆÖs a response, explains Gadd, ŌĆ£to being surrounded by too many fucking pathological optimists. If you always think positive thoughts, you might have super high confidence, but youŌĆÖre going to get bit.ŌĆØ

McClurg conceived┬Āof the X-Rockies expedition long before Gadd got involved. ŌĆ£At first, Will wouldnŌĆÖt even consider it,ŌĆØ McClurg says, mainly because the original plan required too much hiking. Gadd eventually signed on, but only after McClurg agreed to make some changes to the route and strategy, which included more flying and much less tromping. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm a pilot, not a backpacker,ŌĆØ Gadd says.

McClurg, who is five-eight and ripped like a mountain gorilla, grew up in South Lake Tahoe, California, where his parents divorced when he was six. His father, Jack, took their boat; his mother, Jan, got the tent trailer.

ŌĆ£We made two or three trips every summer in that trailer,ŌĆØ Jan told me. ŌĆ£Our big one was always to Yosemite.ŌĆØ A single mom, she couldnŌĆÖt stray from camp because she was caring for McClurgŌĆÖs sister, who is five years younger. ŌĆ£So I had to just let him go and trust that heŌĆÖd be OK,ŌĆØ she says.

ŌĆ£Paragliding is a sport that is least defined by its numbers,ŌĆØ Gadd says. ŌĆ£It's the freest sport I do in my lifeŌĆöand the expression of that is what Gavin and I did.ŌĆØ

McClurg would often disappear from dawn until dusk to explore the park. Half Dome was his favorite place, and he first hiked it, with a buddy, when he was nine. ŌĆ£I decided a long time ago I canŌĆÖt lose sleep and worry about him,ŌĆØ Jan says. When I ask McClurg about this, he agrees that he had plenty of freedom. ŌĆ£When I was 11, my mom would go on business trips for a week, and I was the babysitter for my sister. These days sheŌĆÖd be put in jail for doing that. But it taught me very early on what I was capable of, allowing me to believe that anything is possible. Now I tend to be overconfident, especially with flying.ŌĆØ

During the expedition, Belcourt and a few fellow pilots have been keeping tabs on its progress, and theyŌĆÖve been relishing the idea of these starkly different personalities being together, in a sport where it can be distracting and even dangerous for two pilots to fly in close proximity. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre all wondering how Will is dealing with Gavin, joking about it,ŌĆØ Belcourt says. ŌĆ£This crazy optimist with Will.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre trying to realize your own potential in a place where no one sees and no one cares,ŌĆØ Belcourt has said of paraglidersŌĆÖ penchant for solitude.

ŌĆ£There is a purity in that.ŌĆØ And yet there are situationsŌĆöa longitudinal traverse of the Canadian Rockies, for instanceŌĆöwhere solo flying would be suicide.

ŌĆ£The biggest technical problem with paragliding is seeing the sky and understanding how it works,ŌĆØ Gadd explains. And unlike a typical flight, where pilots soar to wherever the thermals are working best, Gadd and McClurg want to adhere to a predetermined route that will lead to the U.S. border. This means that every second in the air requires a relentless search for clues that will help them navigate south.

ŌĆ£With two people, you have twice as much information about whatŌĆÖs going on in the atmosphere,ŌĆØ Gadd says. ŌĆ£We can sample a lot more air and up our odds.ŌĆØ┬Ā

On our third night trapped in camp, Gadd fishes a bottle of cheap whiskey from his pack, takes a swig, and passes it to me. ŌĆ£What weŌĆÖre flying through is without a doubt the deepest, most dangerous, and most sketchy terrain anyone has ever flown on a paraglider, so it just helps having someone out there with you,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£There is a lot of stress involved flying in these gnarly conditions,ŌĆØ adds McClurg, who says that partnering up has given him ŌĆ£a psychological boost. ItŌĆÖs like, Well, if heŌĆÖs up here, I must not be totally crazy! And you know heŌĆÖs thinking the same thing.ŌĆØ

It's the fourth day at our high camp, and the pilots are piling on layersŌĆömerino-wool long underwear, down jackets, glovesŌĆöto stay warm in the frigid air at higher altitudes. ŌĆ£During the expedition, 13,000 feet has been normal for us,ŌĆØ says McClurg, who drops his pants to install the final piece of gearŌĆöa strap-on catheter, so he can urinate in-flight.

By noon the thermals are cranking. Gadd and McClurg roll out their wings and launch. In only nine minutes, they climb 1,900 feet. I can barely see them, but I can hear their variometers. The device helps pilots find the so-called core of a thermal by repeatedly emitting audible chirps that scale higher during ascents (when theyŌĆÖre in the core) and lower during descents (when theyŌĆÖve moved outside it). Four hours and 42 minutes later, theyŌĆÖve landed in a meadow at 7,200 feet, having traveled 68 milesŌĆötheir second-longest one-day gain on the expedition. (The longest: 94 miles.) In his journal, McClurg writes, ŌĆ£Best flight of my life. Most committing, beautiful, crazy, fun, wild, exceptional aviation experience IŌĆÖve ever had. Totally insane. Will reckons we went 50 miles with no landing options. Will and I feel at this point the rest of the expedition is just gravy, weŌĆÖve survived the hardest part.ŌĆØ

A short while later a cold front rolls in, grounding Gadd and McClurg for eight days. ŌĆ£The goal of the U.S. border became this imagined line that Will and I started to think was pointless,ŌĆØ says McClurg. TheyŌĆÖre pinned down and despondent near the town of Invermere, 120 miles from Montana. Gadd asks himself, Is this it? WeŌĆÖre done? WeŌĆÖre never going to get it going again? Later he tells me, ŌĆ£I looked at the distance remaining and figured itŌĆÖs not going to happen in the amount of summer we have left. The flying season ends in mid-August, when early fall starts.ŌĆØ┬Ā

But finally they get a breakŌĆötwo days of sun, which reaps them another 100 milesŌĆöbefore persistent rain settles in. ŌĆ£We were flying in the most turbulent, whacked-out conditions ever,ŌĆØ Gadd recalls. ŌĆ£I run paragliding competitions, and we cancel them when conditions are too strong. If we were flying in a competition, I would have canceled most of our flying days.ŌĆØ

It's nearly two weeks later, on September 4, before theyŌĆÖre airborne again. Rested and resupplied, they launch late in the afternoon and barely cover 15 miles in two hours. They land in a snow-dusted meadow just below the summit of Mount Broadwood (7,299 feet) to pitch camp. And then McClurg realizes that he left his tent behind. ŌĆ£By about 9:30 p.m., I was encased in a pretty nice ream of ice,ŌĆØ he says later.┬Ā

In the morning, clear skies prevail. But the late-summer sun is weak and canŌĆÖt fuel reliable thermals. Plus, Gadd is sickŌĆöa nasty head cold. They launch anyway, with the U.S. border a mere 20 miles ahead, but they have trouble gaining altitude. After 90 minutes, they wrestle their wings up 300 feet, just enough height to get themselves across a wide glacial valley. ŌĆ£We would have been on the ground if we didnŌĆÖt get to the next thermal,ŌĆØ McClurg says. ŌĆ£I felt like it was do or die.ŌĆØ┬Ā

ItŌĆÖs a few minutes past 5 p.m. when Gadd and McClurg discern a succession of peaks, aligned north to south, known as Inverted Ridge. It appears to be a straight shot to the border. At 6:45, with less than an hour of daylight remaining, Gadd notices a 50-foot-wide clear-cut running east to west. He checks his GPS. ŌĆ£Holy shit! WeŌĆÖre over the border,ŌĆØ he shouts to McClurg over the radio. Both pilots are screaming and hollering and doing air high-fives.┬Ā

By sheer chance, their final flight ended near a logging road that led them out of the wilderness. All told, their north-south linear distance totaled 497 miles. Add in detours and backtracks, and they easily covered twice that. During the monthlong expedition they completed 15 flights, which averaged about 32 miles each. ŌĆ£But numbers donŌĆÖt tell the story,ŌĆØ insists Gadd. ŌĆ£Paragliding is a sport that is least defined by its numbers. ItŌĆÖs freedom that defines it. ItŌĆÖs the freest sport I do in my lifeŌĆöand the expression of that is what Gavin and I did.ŌĆØ He goes on: ŌĆ£The route we flew had never been flown in a paragliderŌĆöand may never be flown again. The blank areas on the map used to scare me. Now IŌĆÖm like, ŌĆśLetŌĆÖs go there!ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

Michael Behar () wrote about snow-prediction expert Joel Gratz in July 2013.