Ain’t It Just Grand

Climb aboard for the ultimate ride with the ultimate boat buddy: Martin Litton, the Colorado River legend and conservation warrior who, as much as any other single person, shaped the Grand Canyon float trip into an American classic

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

It's a blustery April afternoon on the Colorado River, deep inside Grand Canyon National Park, and from his seat in the stern of a handsome little boat called the Sequoia, Martin Litton has just taken note of an intriguing development. Normally, the river down here is restless and kinetic, sluicing along with a muscular roll of its shoulders. At the moment, though, the current has mysteriously disappeared, and the water's surface has taken on the heavy, sullen stillness of a polished green gemstone.

Litton strokes his beard thoughtfully, then casts a glance behind the Sequoia to the boat I'm in, a yellow supply raft manned by a nervous-looking 57-year-old named John Blaustein. J. B., as everyone calls Blaustein, is sporting hipster shades and a cocoa-colored cowboy hat.

“You know, J. B.,” Litton calls out, “when things get all calm like this, it means the river's backed up by something. And in this case, what it's backed up by is an absolutely terrifying pile of boulders called Dubendorff.”

“Jesus, we're coming up on Dubendorff?” Blaustein yells back. A former Grand Canyon guide, J. B. now lives the agreeable life of a Berkeley-based commercial photographer, but once every summer he allows himself to be dragged down the river again. During these ordeals, he spends half his time pretending to complain about absurdly minor discomforts, the other half awash in a lather of angst over rapids like the one we're about to enter.

“I'm afraid it is,” replies Litton, who's clad in a straw hat, an indigo shirt, and black suspenders—an ensemble that makes him look like an Amish farmer gone to sea. “This is a terrifying place, J. B. Absolutely terrifying.”

“Absolutely terrifying” is Litton's favorite expression, a phrase he invokes several times an hour to describe everything from shifting weather patterns to the possibility that the six liters of Sheep Dip Scotch stowed in his hatch might run dry before the conclusion of this 280-mile odyssey through the rapids of the Grand Canyon.

There are 80 of these named rapids, a dozen of which serve up some of the biggest whitewater in North America. And though Litton and Blaustein know that Dubendorff, which marks the midpoint of most canyon trips, doesn't rank among the worst, it's not to be taken for granted. The run is a maelstrom of huge waves and sharp pour-overs that sound like the afterburners of an F-16. In the brief cushion of tranquillity before all hell breaks loose, Litton has a final thought to share.

“J. B.!” he barks.

“Whaddaya want now?”

“Do you know what the greatest pleasure in life is, J. B.?”

“No, Martin. But before we enter the mother of all rapids here, I'm sure you're about to tell me.”

Among a few other small vices, Litton delights in reciting scraps of literature; today's offering comes from Kenneth Grahame's 1908 classic, The Wind in the Willows.

“There is nothing,” he declares, “absolutely nothing, half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” Well, damn. As every Grand Canyon guide knows, this pronouncement by the river-loving Water Rat is potent stuff: the closest thing dirtbag boatmen have to an Apostles' Creed. Which is why Blaustein can only sit there looking trumped as Litton—who is currently 87 years old and may be making the last of his many, many runs through the canyon—lets fly with a wicked peal of laughter that booms off the soaring walls.

“TouchĂ©, Martin,” replies Blaustein, touching the brim of his hat as Litton and the Sequoia are seized by the current and abruptly disappear over the edge of Dubendorff. And with that, we follow the old man into the thunder.

Every trip down the canyon is special, but this trip is particularly fine because the man at its center has no antecedent. In the annals of Grand Canyon boating and conservation, Martin Litton is a unique force of nature, a tornado of ungovernable passions, soaring eloquence, and stiff-necked defiance quite unlike anything else that's ever blown through one of the most storied locales in American adventure.

Born in Gardena, California, in February 1917, Litton grew up exploring the California wilderness, served as a glider pilot in World War II, and started taking trips down the Colorado back in the fifties, eventually becoming the only outfitter to guide the river's ferocious rapids exclusively in the frail wooden boats known as Grand Canyon dories. These double-ended, flat-bottomed craft, which he played a key role in designing, are radically different from the ponderous oar boats that Major John Wesley Powell used during the first descent of the canyon, in 1869. Beautiful, delicate, and graceful, became—and remain—the sacred craft of the canyon.

Along the way, in his roles as a freelance writer for the Los Angeles Times, an editor at Sunset magazine, and a board member of the Sierra Club, Litton also elbowed into some of the most important environmental battles of his time. In 1956, he helped block two dams inside Utah's Dinosaur National Monument, and in 1967 he and others thwarted several dams on Idaho's Snake River. Thanks to Litton's years of public drumbeating on behalf of California redwoods, he's sometimes called the Father of Redwood National Park, which was signed into being in 1968. In that same year, he helped lead what is probably the biggest of all his crusades: a successful campaign to kill a pair of dams that would have stilled the Colorado as it winds through the Grand Canyon.

Today, Litton merits double-barreled distinction as one of the founding commercial river runners of the Colorado and one of America's greatest living conservationists: a man who, after 70 years of both reveling in and battling to preserve a treasure trove of natural wonders, has become something of a national treasure himself.

For all his accomplishments, though, there have always been contradictions, mostly in the form of Litton's puzzling personality quirks. He has fought for all sorts of restrictions to protect fragile landscapes, yet he loathes any government agency that musters the temerity to tell him where he can go and how to behave when he gets there. He inspires great loyalty, but his former employees describe him as the sort of mercurial boss who could switch in a heartbeat from charming to curmudgeonly to nitpicking. He bemoans the loss of solitude in wilderness but made his living by encouraging millions of people to go out and discover it. He's a paragon of environmental rectitude, and yet, throughout the sixties, in what Litton says was an action suited to “different times,” he concluded his 21-day canyon trips by dumping nearly a month's worth of empty beer cans and liquor bottles into the Colorado, telling his guides that “studies have shown the river to be deficient in silica and aluminum.”

“A very, very complicated person with deep flaws who has done extraordinary things,” says Brad Dimock, a river guide who's known Litton since 1973—and who, like everyone close to Litton, harbors sentiments colored equally by affection and exasperation. “I don't think you'd find a single heroic figure who isn't also burdened with contradictions. And when you look at the Grand Canyon today, it's impossible to say that Martin didn't make one hell of a difference.”

Perhaps Litton committed himself to the nation's most spectacular waterway because this landscape mirrored some of his own paradoxes. The canyon's signature attribute is a frigid river tumbling through a savage furnace of sun-blistered rock—a theater of hellish beauty whose sublime charms are matched only by the concussive force of its harshness. Held up as the supreme example of nature's forces laid bare, it is also a labyrinth of abiding mystery that's best grasped by traveling in the company of a man whose character, like the canyon itself, defies any attempt to contain it.

[quote]“The Grand Canyon is America's greatest scenic treasure—an experience made to order in wonder,” Litton declares. “Floating a boat down the Colorado? Why, it's simply the best thing one can do.”[/quote]

“There's just no explaining the old fart,” Dimock concludes. “He's still out there fighting his battles and rowing his frickin' boat. I just want to know when his last river trip's going to be.”

Last spring, Litton's former guiding company invited him to return for one more run. And so Litton duly presented himself before a group of bright-eyed passengers who'd paid up to $4,314 apiece to float alongside the most notorious boatman and rebel ever to drift the Colorado in a cloud of rapture.

“The Grand Canyon is America's greatest scenic treasure—an experience made to order in wonder,” Litton told the clients the night before they hit the river, congratulating them on having the good sense to join him. “Floating a boat down the Colorado River? Why, it's simply the best thing one can do.”

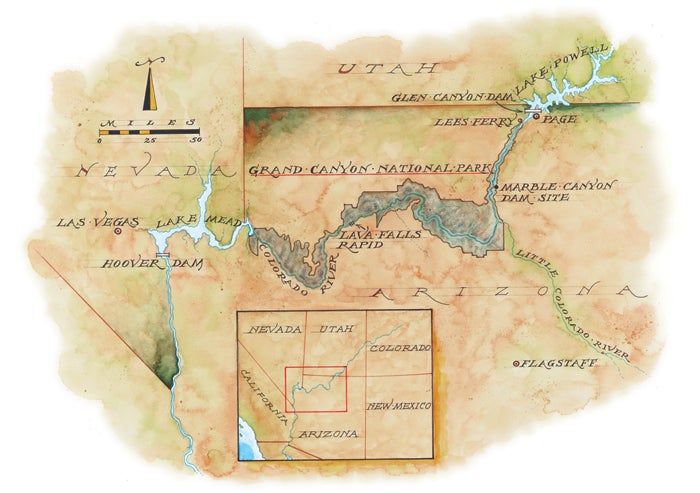

We begin where all Grand Canyon journeys begin: at Lees Ferry, 15 miles downstream from Glen Canyon Dam. Gathered at the put-in ramp around three bulbous baggage rafts and six elegant, scimitar-shaped dories are 18 passengers from all over the United States, among them Duane Kelly and his wife, Cosette, a pair of retired teachers from Kansas City; Pat Newman, an accountant from Golden, Colorado, here with her husband, Dennis, who invents devices to monitor medical patients; and Devon Meade, a singer from Los Angeles, who used to perform backup vocals for Alice Cooper. An eclectic hodgepodge, the clients are united by the simple fact that all of them want to see the canyon and the river through Litton's eyes while it's still possible.

The trip has been outfitted by , the Angels Camp, California, company that now owns Litton's old guiding concession, and it's being led by Bill “Bronco” Bruchak, a barrel-chested former beer distributor from Pennsylvania who's been running the canyon for 28 years. Bronco is joined by Rondo Buecheler and Eric Sjoden, who have worked the river for nearly three decades, along with three members of the “Dale dynasty,” the most illustrious family in Grand Canyon dory guiding. Sue “Coyote” Dale—whom everybody calls 'Ote—is here with her son, Duffy (who started rowing a dory at the age of three while perched on his father's lap) and Duffy's uncle, Tim. Rounding out the crew are the baggage boatmen: Curtis Newell, Ryan Howe, and their grumpy court jester, Blaustein, who has known Litton since 1970 and collaborated with him on , a 1977 book that stands as the definitive tribute to boating on the river.

While the crew rigs the boats, Litton sits quietly in the Sequoia, his physical appearance bespeaking both weightiness and mileage. The skin on his face, framed by a thick white beard and mustache, is creased with wrinkles and flecked with broken veins. His eyes are a startling shade of blue. The backs of his powerful hands are covered with liver spots. Together, these features make him endearing and intimidating all at once—part Santa Claus, part Old Testament prophet.

Litton has been through the Grand Canyon at least 35 times, but even he doesn't know the exact number. In 1997, then 80, he set a record, which still stands, as the oldest boatman ever to run the canyon, rowing every rapid himself. But recently his age has started taking a toll on his reflexes, which is why the setup on this trip is a bit different.

Litton will spend the better part of each day rowing the Sequoia, but when we hit some of the more technically challenging rapids, Tim Dale will have to dance out of the stern and try to convince Litton to hand over his oars. It's an arrangement that will force Litton to take a backseat just as the action gets good—something that cuts directly against his grain. Over the years, Litton has won his share of victories and also tasted some bitter defeats; but in conservation battles and on the river, he has held steadfastly to the idea that you never compromise and never surrender.

“People always tell me not to be extreme,” Litton declares. ” 'Be reasonable!' they say. But I never felt it did any good to be reasonable about anything in conservation, because what you give away will never come back—ever. When it comes to saving wilderness, we can't be extreme enough. To compromise is to lose.”

For a man like Litton, relinquishing control is an onerous thing. “Try not to write too much about Martin not rowing all the rapids,” Tim whispers to me as the boats are being loaded. “This is the stuff that just breaks his heart.”

When the last of the drybags are finally stowed, Bronco gives the word and we shove off. As we drift downstream, the cliffs soar upward in a layered tapestry of pastels: pinkish limestone, buff-colored sandstone, and deep-red shale. The combination contrasts well with the brightly painted hulls of the dories.

Along with their colors, the most noteworthy features of these boats are their sharply pointed bows and sterns and their “rocker”—that is, the way their bottoms flare up quickly at the front and back. The design enables a dory to ride dry in all but the roughest water and to pivot with extraordinary quickness, because only part of the hull is touching water at any moment.

Bronco, Litton, and the other pilots send their 11-foot oars planing through the water with smooth, powerful strokes. As the blades emerge at the end of each stroke, the boatmen rotate their wrists with a subtle snap—a technique known as “feathering,” which turns the blades parallel to the river's surface and sends droplets flicking off the ends, flashing in the canyon light. The rhythm is crisp, silent, precise.

Feather . . . flick . . . flash . . .

Breaking the water into V-shaped ripples, the dories achieve a visual alchemy seen nowhere else. They appear to be suspended partly on the surface of the river and partly—through a trick of rocker and the magic of their radiance—on the air itself.

We won't see a horizon line again until we emerge from the canyon, in three weeks.

Over the next few days, a routine sets in. In the mornings we make our miles, pausing at side canyons for lunch and hikes. (Litton always skips the hikes but demands detailed field reports on which flowers are blooming.) By late afternoon we've usually reached camp. While the guides make dinner, the passengers gather around the Sequoia, break out cocktails, and listen to Litton hold forth. Our nights are dark and silent and studded with stars.

On the afternoon of the third day, we pull over at a beach where Bronco points to several large bore holes that, back in the fifties, were dynamited into the cliffs lining both sides of the river. This is where the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation once proposed anchoring the Marble Canyon Dam, a concrete wall that would have created a lake stretching all the way back to Glen Canyon Dam. A second structure, Bridge Canyon Dam, just above the edge of Lake Mead, nearly 200 miles downstream, would have drowned the bottom portion of the canyon. The spot we're standing on would have been submerged beneath a 300-foot-deep lake.

[quote]In the fifties, using the graceful wooden boats called dories, Litton helped pioneer Grand Canyon whitewater. In the sixties and seventies, he helped block two dams that would have turned the Colorado River into a lake.[/quote]

Back in the sixties, when construction was slated to begin, the Sierra Club was prepared to accept these monoliths as a necessary evil, a concession Litton deemed ludicrous. By 1963 he'd goaded David Brower, the Sierra Club's executive director and a man who once called Litton “my environmental conscience,” into waging an all-out war against the scheme. When the dams were finally stopped cold, in 1975, the environmental movement that Litton had played such a central role in creating—usually without taking any credit—had scored one of its greatest victories.

Standing here, it's hard to imagine a better illustration of the impact one person can have. But the sight of the holes appears to send Litton wandering off into a more sobering mental landscape: the wilderness of his own regrets. “In so many ways, the American West really was a paradise, but look at it now,” he tells the clients, who've gathered around him. “All you see are places that have been ruined because of greed. Ugliness. We had a paradise, and we lost it.”

One of the passengers asks Litton if he thinks he made a difference. “I don't know,” he says quietly, staring at his feet. “I suppose I never really succeeded in much of anything.”

The passengers find Litton's comments disconcerting. But to boatmen like Blaustein—who know the full scope of what Litton achieved—his words just seem dead wrong.

Litton made his first trip down the Grand Canyon in 1955 with an early guide named P. T. Reilly, a venture that inspired him to start putting his own trips together. This was at the dawn of commercial river running, when pioneering outfitters like Georgie White and the Hatch brothers were experimenting with army-surplus pontoons, which would morph into the 30-foot motor rigs and 18-foot oar rafts that are now the mainstays of Grand Canyon guiding. But for reasons of tradition, aesthetics, and stubbornness, Litton was determined to stick with wood.

The most promising design was a modification of a Grand Banks cod-fishing dory called a McKenzie driftboat. In the early sixties, Litton purchased a handful of these craft from two Oregon boatwrights and began taking friends down the Colorado. Every summer, more people signed up. And every winter, Litton dashed back to Oregon for more boats, ordering up design changes with each batch.

It was all pretty much a lark until 1968, when a story Litton had written at Sunset about threats to the California redwoods was spiked and Litton, in a fury, resigned. Within a few years, he'd become both a full-time wilderness activist and the admiral of a tiny navy of commercial dories, each painted in a distinctive hue and christened after a natural wonder that, in Litton's eyes, had been heedlessly ruined by man. Names included Hetch Hetchy (a valley just north of Yosemite that was flooded by a dam in 1914) and Music Temple (a feature in Glen Canyon, drowned beneath Lake Powell in the sixties).

Litton recruited his earliest guides from California—most were ski instructors who couldn't tell a gunwale from a chine but were willing to fling themselves down the Colorado armed with little more than cutoff jeans and toothbrushes. Together, Litton and this ragged platoon dedicated themselves to the idea that providing cheap, no-frills trips to high school teachers, Boy Scouts, and housewives would build a constituency of citizens willing to fight to protect the canyon.

During the earliest trips, everybody had to follow the boss. At the approach to each rapid, the boatmen would scramble to clip the passengers into their life jackets while Litton stood, waved his arms, and explained what needed to be done. “This is Sockdolager—for God's sake, pull left at the tongue!” he'd scream. Each oarsman would relay the message back to the next, then pray he wouldn't screw up too badly. The results were often spectacular.

One summer at Crystal, a rapid Litton's rookie guides were too terrified to row, he took three dories down by himself—hiking up the shore after each run—and flipped them all, shearing off hatch lids, splintering sterns, shattering oars. At Bedrock, the Bright Angel (named for a creek inside the canyon) was sucked beneath a boulder that raked off its entire side. And in 1970, Blaustein managed to ram the Hetch Hetchy into a rock in a rapid called Unkar, splitting the hull from oarlock to oarlock.

“I basically broke the boat in half,” Blaustein recalls glumly.

After each disaster, the guides would repair the worst of the carnage with plywood, duct tape, marine putty, and even driftwood. Then they'd go out and break everything all over again. “That was definitely the golden age of Grand Canyon boating,” recalls Rondo Buecheler. “And what made it golden was there were absolutely no rules, and we had no idea what the hell we were doing.”

When his crew finally started getting the hang of things in the late seventies, Litton stopped leading every trip and instead kept tabs using his company's vintage Cessna 195. He'd load up the plane with blocks of ice and cases of beer and then roar down the canyon at 150 miles an hour, buzzing the tops of the tamarisk trees and looking for his camps.

“We'd hear his approach and it'd be like 'Here he comes; everybody run!' ” laughs Andre Potochnik, a veteran dory guide. “Pedal-to-the-metal Martin. He'd strafe us with supplies, then fly off to Washington to lobby for whatever wilderness issue he was fighting at the time.”

By the 1980s, the dory fleet had become the envy of the river, and its oarsmen sat at the pinnacle of the guiding hierarchy. Whenever Litton returned to the canyon on a trip, boatmen working for motor and raft companies would pull alongside him in the eddies, or stroll over to his camp at night, and beseech him for a job. Around this time, however, Litton's abysmal business instincts—which included giving away trips to virtually anyone interested in conservation—began driving his company to the edge. In 1987, he was finally forced to sell Grand Canyon Dories to George Wendt, the president of OARS. The National Park Service approved the transaction on the condition that Wendt would devote two-thirds of his trips to dory ventures for ten years—a commitment that Wendt has maintained ever since, in honor of the heritage Litton created.

“What Martin did was just nuts,” says Blaustein. “I mean, here was this guy who wanted to run this great big river in these itty-bitty boats that broke every time they hit a rock. But, God, they were beautiful, and riding in them somehow made you feel very humble and pure and connected. And so Martin made it work. That was his vision for the Grand Canyon. It was the way he knew it should be done.”

All along the canyon, news has spread that Litton is on the river. One morning, a party of boaters pulls over to listen while he tells off-color jokes. A few days later, a crew of archaeologists beach their powerboats, whip out a banjo and fiddle, and perform an impromptu riff called “The Martin Litton Breakdown.” Another night, a fleet of rafts pull into an eddy just so the trip leader can toss Litton a bottle of Bombay Sapphire gin. “Well, wasn't that nice?” says Litton, studying the label like it's a lost page from the Talmud. “Who in the world was that fellow?”

Toward the end of our first week, the canyon begins to change. First, the space between the cliffs opens up, letting us see all the way to the South Rim, more than 5,000 feet above. A day later, the walls narrow dramatically, and as the dories enter a ferocious rapid called Hance, the gates slam shut on the Inner Gorge.

This is the subbasement of the canyon. The walls are blacker than coal and the rapids feral. Every day they hit us with staccato bursts. Sockdolager, Grapevine, Horn Creek. Granite, Hermit, Crystal. Waltenburg, Bedrock, Upset. The huge boulders lining these cauldrons create deep, recirculating holes into which the entire river seems to disappear. The current seethes and churns, folding back on itself to form whirlpools, boils, and massive eddies. The rides are fierce, furious, and shockingly cold.

[quote]The boatmen's attachment to their craft is absolute. They fuss over them, paint them with scenery. On winter nights, one guide sometimes soaks in a scale replica of his dory as he dreams about the river.[/quote]

A half-century after Litton's first expedition, these waves are still enormous and their hydraulics explosive, but the challenge is not quite the same. The dories are now made from sturdy, closed-cell foam instead of wood, and oarsmen like Bronco have run the river so many times that it's rare to see them even flirt with a submerged rock. But while much of the carnage has faded, the dories' power over the guides endures.

A typical dory apprenticeship can last nearly a decade, longer than any other in the canyon. By the time a boatman has earned his place, his attachment to these custom-made craft—which cost up to $17,000, more than a season's salary for most guides—is absolute. You can see it in the way the boatmen fret over their dories: spit-polishing microscopic scratches on the hulls, glowering when passengers track dirt onto the decks. Perhaps the deepest evidence of their incorrigible love, however, comes out during the winter, when they're off the water.

Back home in Flagstaff, Duffy spends hours carving miniature replicas of his craft, the Paria, and his mom, 'Ote, touches up the stern of Dark Canyon, which she has decorated with a hand-painted scene of a butterfly landing on a wildflower. In Mesa, Colorado, Rondo tromps across the street to Bronco's driveway, where the men climb into Bronco's boat, the Yampa, wearing their down jackets while they drink Scotch and reminisce about rapids. As for Eric Sjoden, a few years ago he built a scale model one-third the size of his dory, the Virgin, and converted it into a bathtub at his cabin in Whitefish, Montana. He spends winter evenings soaking and dreaming about returning to the river.

“The dories have a grace in design that is astonishing—they're just so fucking gorgeous,” says Brad Dimock, who is coming out of retirement this season because he can't bear to be away from the boats. “The first time I ever rowed one, I was just stunned. And that feeling never really left. They're that cool.”

“What's so appealing about a dory?” says Bronco one afternoon, borrowing a line from Litton. “It's pretty simple. Rafts are ugly. Dories are beautiful.”

By our second week, the canyon isn't the only thing changing: The wind and water have started to peel back the more constrained layers of people's personalities. Doug Vavrick, a political consultant from Seattle, and his wife, Kathleen, frolic naked in the shallows during the evenings. And Pat Newman, who started the trip shy and withdrawn, has turned giddy. Each morning, she dashes around camp giving everyone a hug.

“Hugging's done an awful lot around here,” Litton observes after accepting a postbreakfast embrace. “It's what the younger generation seems to like to do.” (Newman is 60.)

The only person who hasn't transformed is Vernita Allen, but that's because she doesn't need to.

A 73-year-old retiree from Kansas City who's been down the river three times, Allen has undergone extensive cancer treatments and is now so weak that every day the guides have to set her in and lift her out of the boats. She knows this is her last trip. And in the process of bidding farewell to each feature of the canyon, she long ago arrived in the cerebral zone that the other passengers are just now discovering.

“I've seen a few people go down this canyon and not get changed, but not many,” she said to me one day. “There's just something about how minuscule you feel compared to how long it took to put this place together. It seems to put things in balance. It wakes you up. It opens your eyes. And afterwards, things are not the same. It's that space in the middle—that's why I come here.”

When Allen said this, I had no idea what she meant. But then, below Dubendorff, something happens and I do.

While floating along and staring up at the pinkish rock walls, it suddenly seems as if the canyon has reached out and cupped me lightly in the palm of its hand. Part of the sensation has surely come from bobbing down a current of warm air on the surface of a cool, green river. More than that, though, the feeling of languorous buoyancy has arisen from where I find myself in time. The circumstances I've come from seem irretrievably far behind: things that weighed on me at work are now irrelevant. Yet I'm also far enough from the end—of the trip, of the canyon, of this particular moment—that it's unnecessary to brace for reentry. I am suspended in a state of betweenness, not unlike the rocker of a dory. A state in which I can pivot and float in the luminous embrace of a pink-and-emerald haze that—right here, right now—strikes me as our true destination, the marrow of the journey.

A few minutes later, we pull over for lunch. After finishing my sandwich, I spot Litton sitting in the shade of a tamarisk and wander over to ask if he's gotten something to eat. He looks up at me, his blue eyes momentarily vacant, still lost in his thoughts.

“Thank you for asking,” he replies after a long pause. “I've had everything I could ever wish for.”

That, as it turns out, isn't entirely true.

For more than two weeks, Litton has graciously resigned himself to his subordinate role, cheerfully needling Blaustein while Tim Dale gets the Sequoia through the worst whitewater. But as the trip enters its final phase, the frustrations bottled up inside Mr. No Compromise are about to collide with the biggest obstacle on the river.

Just below the Toroweap Overlook, 179 miles downstream from Lees Ferry, the Colorado drops off a ledge and detonates. This is Lava Falls, a chaos of water and rock that, over the years, has ravaged more boats than any other rapid in the canyon. Even today it's a gamble, and when things go wrong, the results can be frightening: boatmen blown from their seats, oars cartwheeling through the air, passengers swimming for their lives.

The night before we reach Lava, Litton has a message for Bronco: “I've never been a passenger through Lava, and I'll be damned if I'm going to start now,” he declares. “I'll walk around.”

The next afternoon, the river is flowing at 9,000 cubic feet per second, not a bad level for running Lava. We'll go down the right side, a route whose entrance is extremely hard to judge. The tongue runs just to the right of a massive ledge hole that claimed the life of a client named Norine Abrams in August 1984.

[quote]Deep in the canyon, I'm suspended in time—pivoting and floating in the luminous embrace of a pink-and-emerald haze that—right here, right now—strikes me as our true destination, the marrow of our journey.[/quote]

A boatman who threads this entrance perfectly has just enough time to square up his bow before the current drives him directly into the center of an enormous, V-shaped standing wave. The hope is that this wave will push the boat slightly to the left. If it does the opposite, the boat rockets right and washes alongside a glistening slab of lava called the Big Black Rock. The rock is where Lava's other victim, a client named Andalea Buzzard, was stripped of her life jacket and drowned in August 1977. (Neither fatality occurred on an OARS or Grand Canyon Dories trip.)

After the crew ties the boats off to the right-hand bank and scouts the rapid, Litton and Bronco put their heads together for a powwow. Then Litton returns to the Sequoia and, without any ceremony, takes his seat at the oars.

“Let's move,” he says quietly.

As we drift into the current, things suddenly get very quiet. Sitting in the Sequoia's bow with Curtis Newell, I can hear only the creak of the oars and the muffled roar of the falls. “Well,” Litton announces, “here we go.”

He handles the entrance flawlessly: You could spit into the ledge hole as we flash past it and slice down Lava's incline toward the V-wave. Litton gets in two good strokes, lining up the dory. Then the V-wave smashes us with the force of a runaway coal truck. The river gathers into a fist and punches straight over the bow, a haymaker of solid water as thick as wet cement. The decks and the footwells are swamped. The boat reels.

In the midst of this mess, I turn to see that one of the Sequoia's oars has been wrenched out of its oarlock. I also can't help noticing that Litton—who's been drenched and spin-cycled like a cat in a washing machine—looks happier and more alive at this moment than any sane 87-year-old probably should. The old fart is actually grinning.

Then I face forward to see that we're sluicing directly toward the Big Black Rock. Litton heaves on his remaining oar with everything he's got. No dice: The rock's coming up fast, and we're about to hit it.

As the river rolls around the massive rock, it tends to create a pillow of moving water that rises and ebbs with each surge. Through a combination of angle, timing, and Littonian luck, the Sequoia arrives just as this pillow is building. Instead of slamming us into the rock, the water cradles the boat for a second, then gives it a nudge and washes us around the left side. The rock's dripping surface races past, almost within reach, and we find ourselves back in the main current, bucking through the tail waves.

“You did it, Martin! You did it!” the boat's four passengers yell.

“I didn't do anything at all!” he protests. “I was rowing shabbily. Very shabbily.”

“Jesus, Martin,” someone calls out, “if you didn't do it, who the hell else did?”

“Why, the boat, of course,” he says, indignant at having to spell out something so obvious. “It was the dory that did it.”

Two days later we make our last camp, on the edge of Lake Mead.

The next morning, Vernita Allen, Pat Newman, and the rest of the passengers bid farewell and board a blue jet boat that will connect them to city-bound shuttle buses. The guides lash the dories and rafts together and, with help from an outboard, begin motoring toward the gates of the Grand Wash Cliffs, where the land flattens and the river sprawls into the slack water of Lake Mead.

Eric Sjoden and Ryan Howe set up a faded purple lounge chair so Litton has a place to sit. Bronco hands him a sandwich that Rondo prepared the night before. While Curtis sets a bottle of cold Dos Equis into the cup holder of Litton's chair, Tim unfolds Duffy's teal-colored umbrella and holds it over the old man's head. Then, as the rig drifts toward the lake, everyone gathers around and sits at Litton's feet. For the boatmen, it's a chance to relish this last bit of river with their old boss and to think about his place in the canyon.

What will probably endure most in the minds of these guides is the memory of how, against all logic and common sense, Litton launched a fleet of frail boats bearing the haunted names of vanished wonders. They'll also remember him as a warrior cut from the same cloth as Ed Abbey and David Brower: a fighter who turned the tables on stronger adversaries. And they'll remember that Litton, at 87, insisted on rowing himself through the fury of Lava Falls.

“He taught us about belief and how to make a stand,” Bronco says to me quietly as we pass through the Grand Wash Cliffs. “He showed us that when you really believe in something, you don't ever compromise. Compromise is what you let the other guy do.”

All those things are surely worth remembering. But what I'll remember from this journey is something different.

I never knew Litton during his period of towering strength, so I won't be able to recall his victories, his militancy, or his fire. Instead, what will stay with me is the memory of how he conducted himself as he confronted forces that can never be defeated—age, infirmity, and time—and how his conduct illuminated the Grand Canyon in an unusual way.

These days, a Grand Canyon river trip is no longer the same pioneering quest it was when men like Powell and Litton first took it on. But what remains is, in some ways, even bolder and more challenging: an odyssey that offers incontrovertible evidence of how small we are—not much different, really, from the fossils laid down 340 million years ago in the Redwall limestone above the Marble Canyon dam site. By imparting this sense of almost overwhelming humility, a trip down the canyon opens the door to insights about the place's deeper relevance.

When you row the river with Martin Litton, you come to understand that the Grand Canyon is “America's greatest scenic treasure” not simply because of the thrills and the fun—which are tremendous—but because it reminds us of who we are, and who we are not, and of what we most need to become. This isn't something Litton ever said to me directly, but I think he knows it in his bones. He knows it because the elements of his legacy—his dories, his canyon, his river—all come together to underscore one emphatic little parcel of truth.

Which is what, exactly?

Well, as it happens, the Water Rat nailed that one, too. “It's my world, and I don't want any other,” he said of the river. “What it hasn't got is not worth having, and what it doesn't know is not worth knowing.”

It's easy to set up a Grand Canyon trip, and you can still arrange to go this year. Since private trips aren't in the cards right now—the National Park Service, which oversees the canyon, has a 12-year wait list and has temporarily stopped adding names—commercial outings are the only option.

Pick Your Boat

Dories: The guide rows while you shift weight to balance the vessel against crashing waves.

Paddle Rafts: You and five others provide the muscle while the guide rudders you through the biggest holes.

Oar Rafts: The most stable ride, these guide-rowed boats give you a platform to lounge and take in the scenery.

Kayaks: If you can handle Class III rapids and paddle for two straight weeks, you can chart your own course.

Pick Your Length

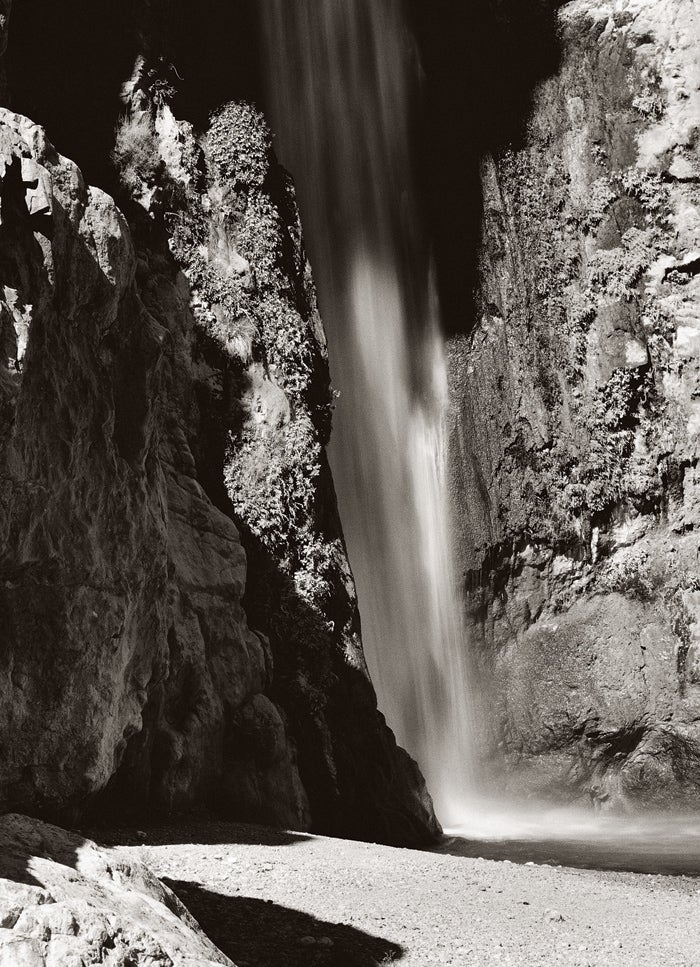

The standard trip runs 225 miles and lasts two to three weeks. You can also opt for the weeklong portions to or from Phantom Ranch. If you have to choose, the lower portion features the best side hikes—like Havasu Canyon, with its three cascades.

Pick Your Month

The river is a chilly 50 degrees year-round, so choose your time based on the air temperature. April, May, September, and October are relatively cool, with highs in the nineties, while June, July, and August days often hit 110. Our pick: October, a cool month featuring postsummer quiet.

Pick Your Outfitter

OARS has run dories and oar boats in the canyon since 1964. Nine to 22 days, $3,213– $5,103; April–October;

Arizona Raft ąú˛úłÔąĎşÚÁĎs offers all-paddle raft trips and “partial-paddle” trips, featuring oar boats for rest breaks. Six to 16 days, $1,565–$3,260; May–October;

America's premier kayak school, the Otter Bar Lodge, runs one Grand trip a year. Non-kayakers can ride in the support rafts. Fifteen days, $3,075; September;

Canyon Explorations/ Expeditions uses oar and paddle rafts and offers specialty trips, including one accompanied by a string quartet. Seven to 16 days, $1,810–$3,485; April–October;

Arizona Outback ąú˛úłÔąĎşÚÁĎs can take you on foot to the pools of Havasu Falls. Three to five days, $1,250–$1,550; March–October;