The Generals in Their Labyrinth

Before the rains, before the winds, before the tens of thousands of missing and dead, Patrick Symmes sneaked into Myanmar's secret capital, where the military rules from a sun-baked plain, guided by the forecasts of astrologers. A report from the last flight out of a shuttered nation, where, even hours before Cyclone Nargis hit, nobody had a clue.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

There never was a man on the ferry to Pakokku, and he didn’t say what he said. I didn’t meet Western diplomats from three nations. Not for coffee. Not for drinks. Not in the official residence, with rain and palm fronds pelting down, just hours before the storm hit.

I didn’t talk with the country’s most distinguished astrologer or its worst comedians. Nobody from any NGOs helped me, either. If I had tea with a prominent intellectual or lunch with a noted businessman, nothing happened. I was just in Burma—sorry, I mean Myanmar—to play golf and look at the ruins.

The boy monks never cried and begged me to conceal their names. At the monastery in Pakokku, they never told me anything at all.

I wasn’t there when the storm hit. There was no cyclone. I didn’t see anything.

The Impact of Cyclone Nargis

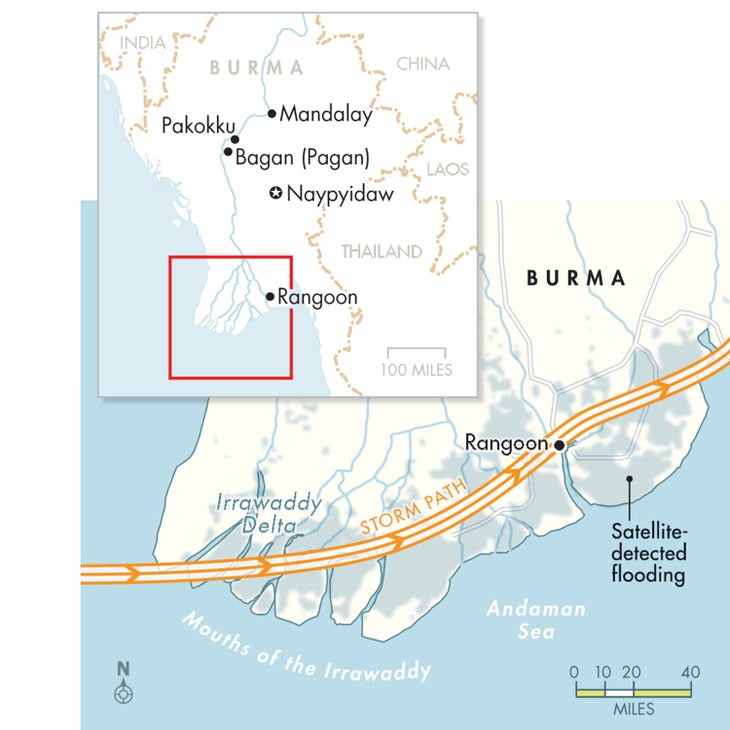

But of course it did hit. I flew out on the last plane out of Burma, on the evening of May 1. On May 2, at 6:30 p.m., Cyclone Nargis came ashore near Labutta, in the southwestern corner of this poor and unlucky country, at speeds of up to 121 miles per hour. Howling in from the Bay of Bengal, the winds shoved a 12-foot wall of storm surge up the delta of the Irrawaddy River. Perhaps 134,000 people died in this initial rampage up the low and braided coastal channels. By dawn, the storm center was in Rangoon, blowing 81 miles per hour, taking more roofs than lives. Then it dissipated inland, leaving some 2.4 million survivors in ruinous condition, without shelter or food or safe drinking water. In some areas, up to 95 percent of homes were destroyed.

In the weeks after the storm, as the waterways went putrid with the bodies of people and some 200,000 water buffalo and cattle, as flooded rice fields were poisoned by salt water, the paralytic failure of the Burmese military government to do anything for the victims of Cyclone Nargis became an international scandal. For weeks the junta’s generals turned away aid from U.S. and French ships waiting offshore, harassed journalists, stonewalled the UN, started and stopped relief efforts, confiscated food donations, finally admitted some international workers, and then denounced them, saying that the Burmese needed no “chocolate bars” from foreigners. Meanwhile, the 40 percent of children in the Irrawaddy Delta who were already malnourished faced months of starvation.

The Burmese were never warned that a cyclone was coming. I was. On the last afternoon of my trip, I waded through knee-deep storm floods to visit one of those Western diplomats you hear from, anonymously, in reports about Burma. We met in her official residence; she was barefoot, in shorts and a red Hawaiian shirt. As we talked, a windy new order was already rattling the patio doors. Palm fronds were spinning through the air like knives. It had been raining for two days. The water was above the grass.

My departure was in five hours. As I left, I asked the same question I’d been asking everybody: Why was there a monsoon in the dry season? I thought it never rained this early.

“This isn’t the monsoon,” the diplomat said, stopping me. “We’re going to get hit by a cyclone. Didn’t you hear?”

No. She’d been notified by her own government and CNN. I, like the vast majority in this country of 53 million, was totally clueless.

I put on my poncho and rolled up my pants, and another diplomat led me down the driveway to the security gate. The Burmese embassy guards pressed a button and then went back to eyeing the sky. Out front, the avenue was flooded, cars throwing up cascades.

“It’s good you are leaving,” this diplomat said as dirty water flushed over his Tevas.

So I got out. I didn’t see the center of Cyclone Nargis, which was closing in on the coast. But before the storm, I saw the center of something else: the bigger, slower, even deadlier disaster that long ago started washing over Burma. I saw how its rulers—through their fear, ignorance, and greed—would end up converting the natural disaster coming down on our heads into a shameful man-made catastrophe, an epic of incompetence and indifference. Let’s call what I saw by its name: evil.

Why ‘Myanmar’ and Not ‘Burma’

Like an Asian Havana, Rangoon is filled with rounded and rusting cars older than I am, and billboards denouncing foreigners. It is a low, humid dump, more Shanghai than Shanghai, stained with mold, clouded overhead by knots of electrical wires, and stuttering and sputtering from the private generators crowded everywhere. (The electric grid can black out half a dozen times a day.) Bicycle rickshaws are loaded up like SUVs, monks and palm readers rule the streets, and laborers sweat all day for pennies. Authenticity is in oversupply here. It’s Asia before the microchip.

I spent my first morning, April 17, at the nation’s most important temple, Shwedagon, a 320-foot-high gold-leafed pagoda that dates back more than a thousand years. It was packed with Buddhist pilgrims for the Thingyan festival, held during the hottest, driest time of year, when people appease the Naga water spirits by shooting squirt guns and launching water balloons in all directions. It was a holiday, and the weeks ahead looked soporific. The forecast was for scorching, humid days with a bit of isolated rain, or what the government newspaper, The New Light of Myanmar, called “generally fair.” The only event on the horizon was a vote on May 10, what Human Rights Watch called a “sham referendum” to enshrine military rule. The New Light urged everyone to vote yes.

Amid thousands at Shwedagon that morning, I saw just one other foreigner. Thailand received almost 14 million visitors in 2006; Burma had just under 300,000. There is a nominal boycott on tourism here, but the real problem is the lack of infrastructure, the limited beaches, and the high costs that scare off many backpackers. The most frequent visitors, other Asians and European retirees, make a circuit through the “Land of Gold,” as Burma is known, from Shwedagon to the ruins of Bagan, a complex of ancient shrines and pagodas grander than Cambodia’s Angkor Wat. They pass through the palaces of Mandalay, the last royal capital, and then head into hill country to take in lakes, forests, and minority ethnic cultures—Chins and Kachins, Karens and Karennis—whose homelands touch on the frontiers of India, China, and Thailand. This Burma is as fetching as it is poor, a backward land that is therefore picturesque and old-fashioned, amid a barefoot poverty that remains nevertheless communal and dignified.

I was equipped with a two-week ticket and a tourist visa that allowed me to slip into this rivulet of foreigners circling through Burma. But I had a very different itinerary, through a different country. I was headed north, to the mysterious new capital, Naypyidaw, a place unmentioned by Lonely Planet. In 2006, the junta—led by General Than Shwe and his 47 cabinet members and “chiefs of state”— announced that all the government ministries of Rangoon were decamping to a location 250 miles north, where a city had been built, from scratch, in the middle of nothing, without warning. I wanted to see the generals’ lair.

It is the military that has trapped this nation in a regressive time sink. A kleptocratic clique of officers presides over 428,000 green-clad soldiers, the second-largest army in Southeast Asia after Vietnam’s. The Tatmadaw, as the army is known, is a cult, really. It was founded by Burma’s independence leader, General Aung San, who fought the British, danced with the Japanese, and was murdered in a hail of bullets by his own officers in 1947, just months before British colonial rule ended, leaving behind a two-year-old daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi. A military coup in 1962 led to decades of isolation and xenophobia; since 1992, the dictatorship has been in the hands of General Shwe, a reclusive, frog-faced 75-year-old with a chest full of medals and an astrologer at his right hand.

The junta has tried to erase history. In 1989 they changed the capital’s name to Yangon and the country’s to the Union of Myanmar, though I’ve found that most people continue to say Burma, either because it implies opposition or it’s quicker. They rebranded themselves as the State Peace and Development Council. Burma’s clocks run half an hour out of step with its neighbors, there are eight days in the week, and, according to The New Light, we’re living in both 2008 and the year 1370 of an ancient Burmese dynasty.

Meanwhile, Aung San Suu Kyi grew up, went to Oxford, married, and returned permanently to Burma in 1988. Now 63, she is an apostle of nonviolence and democracy, known within her country simply as “the Lady.” In 1990, her pro-democracy party won the only free elections in Burmese history; she won the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts, but the junta locked her inside her elegant lakeside house in Rangoon. After 18 years of intermittent imprisonment and release, she is still there—on May 27, the junta extended her house arrest for another year.

Sometimes it feels like all of Burma has been locked in with her. A censorship board controls radio, books, magazines, and television, cellular phones cost $2,500, and the Internet is simply turned off during a crisis. Even in calm times, most e-mail accounts are blocked by a firewall (although bright kids in cybercafés proxy-tunnel to servers in Germany). The day before Cyclone Nargis struck, as the storm began to nip at Rangoon’s roofs, starlets paraded across the screen of my hotel room’s TV set, lip-syncing pro-government ballads.

There is only room for good news in this official Burma. Even disaster reports from a cyclone barely reach the ears of top leaders. “In Burmese culture, you don’t tell each other truth if it will hurt,” Ma Thanegi, a noted Rangoon painter and former assistant to Aung San Suu Kyi, told me. “That is the worst part of our culture. No argument if it hurts feelings. Objective criticism does not exist. Any criticism must be based on hatred or jealousy.”

Thanegi did a year in jail herself for opposing the government. As recently as 2004, Than Shwe conducted a messy purge of the military ranks, arresting hundreds of his own men. Even the country’s cadre of perhaps 400,000 Theravada Buddhist monks is not immune. Last September, during what became known as the Saffron Revolution, thousands of them led pro-democracy protests across Burma, beginning in the town of Pakokku. By the time the military snuffed out the unrest, on September 27, in Rangoon, at least 31 people had died. I was headed to Pakokku, too.

Myanmar’s Generals and Astrology

Back in the days of the British Raj, Burma was considered such a hardship post—so hot, so remote, so difficult, and so lawless—that Rudyard Kipling called it “unlike any land you know about.” Even George Orwell, who spent five years here as a colonial policeman in the 1920s, found it tough enough for his liking. Some intellectuals here see their crazy government prophesied in Orwell’s later books, Animal Farm and 1984. But his 1934 novel, Burmese Days, offers a more direct portrait—a deeply superstitious society in which the strong prey on the weak, and conspiracies are made with witchcraft, magic amulets, and knives in the back.

Astrology is Burma, Ma Thanegi told me. People look for a shortcut, a way to predict their Buddhist karma before it comes back to them. “It’s cheaper than a shrink or a marriage counselor,” she said. “We don’t have any neurotic people thanks to astrologers. If you are failing in your profession or your life, it’s not your fault. It’s because of your stars.”

The generals have taken this national obsession to new heights. U Ne Win, the dictator who completely isolated the country from 1962 to 1988, issued currency in unusual denominations—45 and 90—that added up to his lucky number. In 1970, the story goes, an astrologer said he would be killed from the right, so he decreed an overnight shift from left-hand to right-hand driving on Burmese roads. Than Shwe has continued this prudence, dispatching whole caravans of bureaucrats, and even hundreds of animals from Rangoon’s zoo, to the new capital at auspicious moments. One convoy of 11 battalions and 11 ministries, I was told, left for Naypyidaw in 1,100 trucks at the 11th minute of the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month.

I wondered how my own karma was going to play out. My visa application specifically threatened “legal measures” for snoops who “interfere in the internal affairs” of the country. In addition to Naypyidaw and Pakokku, my dicey agenda included jumping the fence to see Aung San Suu Kyi—something I figured I’d do on my last day in Burma, just before beating a hasty retreat out of the country. So one muggy morning I joined a queue of upper-class Rangoon women outside the office of San-Zarni Bo, said to be one of the best fortune tellers in the land. As his sign read:

MODERN PROGNOSTICATOR SAN-ZARNI BO

B.SC (CHEM)

1ST. DEGREE (SORBONNE PARIS)

He proved to be a brown, bald, and commanding man, with a milky right eye hinting at second sight. As soon as I handed over $30, an assistant inked my hands and pressed them onto gray paper. San-Zarni Bo spent several minutes in a frenzied silence, applying a tape measure, compass, and ruler to the palm prints, making rapid calculations, and filling out charts. Finally, he looked up and delivered a 30-minute monologue in English that boiled down to this: My lucky dates are 1, 3, 9, 10, 17, 19, 21, 27, and 30, and my auspicious letters are A, M, S, T, and J. Any day of the month in that list is auspicious for me; any placename beginning with those letters is good, too. The past five months, he told me, had been full of “annoyances and disturbances.” In two years, I would get married.

“Any questions?” he said.

A few. I was already married, and I had a nine-month-old baby boy at home; you don’t get a better five months than that. But I told him only that I was planning something for my last day here. Something dangerous. Was May 1 an auspicious day? “Yes,” he said. “The first is a good day for you. Go ahead.”

Blessings secured, I set about plotting my immediate itinerary. During the hottest part of the afternoon, I went to the Savoy Hotel, an outrageously expensive relic of British rule, where I ran into another Western diplomat. He suggested the rosé (“made by two Germans up in Shan state”), and I asked about a rumor that all embassies would be moved up to Naypyidaw, far from the bars and markets of Rangoon. He didn’t believe it.

“Isn’t that why they built the place?” he asked. “To get away from foreigners and monks?”

When it was first sprung on the world, Naypyidaw was closed to outsiders. In 2006, American biologist Alan Rabinowitz became one of the first foreigners to visit, on a Wildlife Conservation Society mission to coordinate a tiger reserve in Hukawng Valley. (The generals love tigers more than they dislike foreigners.) Rabinowitz told me I’d never get on the plane to Naypyidaw without special permission, but that the capital did have a “hotel zone.” Meanwhile, I’d heard vague reports of vast golf courses, and read a blog by a Canadian who’d made it in by bus, although he’d been followed and made to stay in the hotel zone. In 2007, foreign press had been flown to Naypyidaw for Armed Forces Day celebrations, always closely minded, but few other journalists had ever gone. Now the diplomat was suggesting I could just get on a plane and go. “You’ll never get into the civil-admin part, or the military part, though,” he predicted.

The locals were dismissive of the place. The generals had moved to Naypyidaw “because of the stars,” a Rangoon gem trader told me with a wry smile. “They spend all our money on this new capital. It is very nice. So nice.”

He was being sarcastic. Naypyidaw was a barren place, he said. “Worst place in Burma. Terrible weather. They can change everything there but the weather.”

How The Secret Capital Came to Be

Building a new capital in the middle of nowhere is actually a fairly normal idea. Brasilia and Washington, D.C., were laid out that way; Kazakhstan is finishing Astana now. But Naypyidaw is anything but normal.

Getting there was the easy part. A Rangoon travel agent looked at me funny but sold me a plane ticket, and no one asked any questions when I boarded a late-afternoon Air Mandalay flight full of colonels and businessmen. At the small Naypyidaw airport, I glommed on to some surprised Thai businessmen, sharing a taxi to their hotel. The hotel zone consisted of a handful of sprawling luxury-bungalow compounds along the airport road, near nothing. All night, I kept jumping out of bed, startled. The geckos on the walls made a sound just like keys tapping on glass.

In the morning, I took the Naypyidaw visitor’s tour—meaning I hired a taxi. No tourists come here, and the few Burmese businessmen who have to visit the capital leave as fast as they can. Among foreigners, only diplomats and people like Alan Rabinowitz have a reason to go. Almost nothing was as rumor had it. In 2007, The Economist posited a “remote mountain fastness”; Time and The Washington Post described a “jungle.” Instead daylight revealed a flat plain covered with rice paddies. Only half finished, Naypyidaw was a brown, barren, and superheated Lego city, a cross between Pyongyang and a gated community outside Phoenix. Rebar poked out everywhere, and women carried firewood on their heads past just-finished office parks. Spread across miles of empty landscape, it was a field of pre-ruins, a folly as ambitious in its way as the pagodas at Bagan.

There was no traffic. I saw one restaurant in the entire city. There were no crowds, no history, no neighborhoods, and so few schools and shops that many bureaucrats have left their families behind in Rangoon. (Even some top leaders have quietly moved back to Rangoon or to the cooler British hill station near Mandalay, Pyin-U-Lwin.) The population—which the junta claims numbers a million—is almost all government workers, sorted by their ministries into housing blocks and carried to work each morning together in the backs of army trucks.

Naypyidaw is really an open-air prison, where functionaries twirl their fingers at make-work jobs and generals loot the budget. Although U.S. and EU economic sanctions have driven out many international companies, Chevron still does business here, and Naypyidaw is buzzing with deals on oil, natural gas, gems, timber, and hydropower—deals made largely with Burma’s needy neighbors, China, India, and Thailand. In my hotel, the Thai businessmen had been discussing drilling technology. No wonder: Many of the lights in Bangkok are powered by natural gas from Burma, and according to The New York Times, the Thais pour $1.2 billion into Burmese accounts each year. As yet another Western diplomat explained it, the revenues from oil and gas exports are paid in dollars, which the junta converts to Burmese kyat at an official rate of six to the dollar. In Rangoon, I was routinely getting 1,100 kyat to the dollar. So where did the other 99 percent of the oil and gas billions go? Take a guess. After a while my driver turned around and looked at me pointedly. “Want see?” he said.

He didn’t wait for an answer, veering down a broad avenue through rolling country. This was the civil-admin section, the zone that the Savoy diplomat had claimed I would never enter. One by one came the gleaming ministries, mile after mile of countryside dotted with occasional buildings, all new, all labeled, with color-coded roofs. The Ministry of Progress of Border Areas (black roof) is in charge of the military’s endless war on the tribal people. The Ministry of Health (blue) oversees the worst health system in Southeast Asia. The Ministry of Home Affairs (pink) is in charge of catching journalists on tourist visas.

I didn’t see an education ministry or a ministry of justice: The junta does not bother to operate a court system.

The one thing they did have in Naypyidaw was emergency services. In the middle of wilderness, I saw a brand-new fire station. Miles away, amid more emptiness, a police station, bearing the Orwellian slogan MAY WE HELP YOU? One of the tallest buildings in Naypyidaw is an eight-bay firehouse with a watchtower. With its strong concrete and inland location, Naypyidaw never felt the cyclone’s winds. Three hundred miles down in the Irrawaddy Delta, however, where damage was worst, the generals had not bothered to build rescue squads or sheltering police stations. No, we will not help you. When Nargis hit, the military put its head in the sand.

Notes from the Field: Naypyidaw

It is said the generals live in a bubble when they’re outside Naypyidaw, and a bunker when they’re in. I found the bunker. “Want see?” my driver asked again. I nodded, and he detoured far into the east of the city. He showed me a simple gate in the middle of trees, which led to an invisible nightclub for the Tatmadaw. On a roundabout, there was a closed exit that led to the “top man restaurant,” the cabbie said. A gate, glowing with red warning lights, led to a park and playground for the junta’s families. What looked like a partial stadium turned out to be a multistory driving range. Where Rangoon had blackouts, Naypyidaw had penguins, living on ice, their habitats cooled by 24-hour power.

Finally we came to a vast intersection cordoned with razor wire and watched by police. “Than Shwe house,” my guide said, pointing discreetly. There was an eight-lane road of white concrete, leading thousands of feet down to a triumphal arch and, beyond that, the houses of Dictator No. 1 and the other cronies.

“No photo!” the driver screamed, too late.

But you don’t need a camera to get a peek at the weird world of the junta: On YouTube, just type in “wedding of Than Shwe’s daughter.” As the resulting video shows, the generals are not in isolation. “There are hundreds of rich people around them, flattering them,” said Ma Thanegi, the painter. “A nouveau riche, kitschy society, unbelievably luxurious and conformist.”

Than Shwe may have “lots of old-man diseases,” as the barefoot diplomat had told me, but he plays golf, and I hit Naypyidaw’s City Golf Course, hoping to crash his foursome. No such luck: A manager standing beneath a portrait of Than Shwe said they wouldn’t let me play ($20), I wasn’t a member ($20), there weren’t any caddies ($20), and I had to buy a City Golf Course shirt in red ($6).

I balked at the shirt. Five days ago, The New Light of Myanmar contained pictures of regime cronies playing golf in Naypyidaw. A general named Thiha Thura Tin Aung Myint Oo (identified as “Secretary-1”) had inaugurated a tournament on April 16. In the photos, which I held up, Secretary-1 was not wearing an official shirt.

I had to buy the shirt. Equipped with a hugely optimistic two balls, I grabbed a caddy and hit the links as the temperature reached 104 degrees. The nice thing about being dictator is that nobody denies you a mulligan. My first pair of tee shots went a total of ten yards, so I took a third, like Than Shwe would. On the second hole I had a couple of good drives and two-putted; on the third I sliced into the barbed wire and lost the ball. On five, I hit a sweet drive of 175 yards (“Three hundred!” my caddy insisted). Six, which looked onto a construction site, saw my best drive yet, but I three-putted. On seven, I discovered that the official shirt had dyed my belly a sweaty pink. On eight, I took a penalty rather than play my ball off a mound of snake holes. On nine, I hit into a water hazard, twice, which the caddy forgot while scoring me a decent 50. A lie. Here was the general’s ideal country, a back nine of yes-men to carry the bags and ask no questions.

A Journey to Pakokku

M is auspicious for me, so on April 23 I flew out of Naypyidaw to Mandalay, the last royal capital. For two days, there were heavy rains here, which plunged the city into darkness and left the Burmese grinning: rain, in the dry season! But when I hired a taxi and drove southwest, across the paddy-flat plains of central Burma’s “dry zone,” the fields were powdery again with dust. The temperature climbed over 100 and then kept rising during a long day of rumbling down increasingly desperate roads, impoverished children chasing after the car.

I was headed for the town of Pakokku, the place where the Saffron Revolution had begun. The Burmese were once allotted two gallons of gasoline a day, at subsidized prices. Last August, the junta—having sold Burma’s own hydrocarbons abroad—eliminated the subsidy. The cost of bus rides, running a generator, even eating a bowl of rice, jumped as much as 500 percent. The unrest, which started as a protest about the price of gas and exploded into nationwide demonstrations, was sparked at one monastery, in Pakokku.

The town is on the west bank of the great Irrawaddy, which cleaves and defines Burma. To get there, I had to catch a riverboat at Bagan, where thousands of ancient temples squat on the river’s east bank. There are more than 4,000 Buddhist structures here, built between the 11th and 13th centuries; more than 2,000 still stand, from tiny shrines to 18-story numbers rivaling the tallest of the Maya pyramids at Tikal.

In the off-season of an off-country, with the temperature hovering somewhere near 110 degrees, even the trinket vendors had retired. There were a few Spaniards and Germans about, but at one of the world’s greatest archaeological sites, I had a temple—a dozen temples—to myself at sunset. If the government were less charmingly North Korean, less reeking of Cambodia in 1978, Bagan and Burma could mean a great deal to the world.

Early the next morning, I boarded the slim, crowded ferry to Pakokku. The passengers included market women, giggling students, and an English-speaking professional, who at first talked freely about the Saffron Revolution and what he’d seen. Eventually he realized that I was a journalist and recoiled.

The docks were full of informers, he warned me. Spies were everywhere.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “I can’t get involved in politics.” He stared into the dirty bilgewater for the rest of the trip.

No one was waiting on the dock to arrest me. I visited Pakokku’s garish pagoda, filled with glass tiles, gold paint, and real birds flitting past murals of bodhi trees. I hired a rickshaw and went to the particular monastery where the Saffron Revolution began. There, the giggling young monks gave me lumps of palm sugar and showed me their teak longhouse, with its dusty library full of tripitaka scriptures and colonial-era British encyclopedias and a Bengal tiger pelt on their teacher’s throne.

But now there was no teacher. Roughly 150 of the monastery’s older monks had been “sent home”—a form of house arrest—by the junta in the wake of the rebellion. The unrest started on September 5, when several hundred monks began a march for the poor, chanting, “Release from suffering,” their way of asking for lower gas prices. On the town’s only bridge, their moral force met the junta’s plain old force: warning shots, beatings, and arrests. That kind of repression is normal for Burma, but then the army, people in Pakokku told me, tied up one of the monks and left him, bound in the street, for a whole day, roasting in the sun.

You do not humiliate monks in Burma. The next day, when a government delegation came to the monastery to apologize, a mob burned their squad car and then smashed up the business of the town’s biggest snitch. Inside a week, word of the beating of several monks had spread, and tens of thousands of his colleagues took to the streets. Almost every town in Burma saw demonstrations, led by the red-robed clerics and followed by angry students and just about everyone else. But in Rangoon it ended. On September 27, at the Sule Pagoda, a miraculous gilded landmark that sits inside a traffic circle, the army lashed back, shooting into crowds. Officially, 31 died over the course of the unrest, but human-rights groups say it was hundreds. The revolution was put back in a bottle, for now at least.

Not that anyone told me any of this in Pakokku. Later during that burning afternoon, at the well in their monastery courtyard, the monks never warned me that we were under surveillance or said that they were just young initiates, left behind, afraid.

They never cried and asked me to forget their words, their names, and their faces.

The Onset of Cyclone Nargis

The whole way back down to Bagan, the wind was blowing so hard that the boatman wrapped his head in a checked longyi, a kind of sarong, against the stinging sand. The Irrawaddy was enormous even in the dry season, light brown and dotted with overloaded sailing canoes. We sputtered through back channels lined with reeds, eroding sandbanks, and impoverished hamlets on stilts. These shacks were mostly made of bamboo and woven grass and stood only a couple of feet off the ground. The cyclone would only brush through this area, but downriver it would hit with full force on more than a million people living like this—fishing with nets or lines, crabbing, and cutting down the mangroves that would normally protect them from a storm surge. Cyclone Nargis would smash their houses and boats to pulp, like Hurricane Katrina hitting a New Orleans made of cardboard. The storm surge flooded about 30 percent of Burma’s best rice paddies with salt water and rotting bodies. In a disaster, the timeless qualities of Burma turned out to have 16th-century consequences.

It started to rain hard on the approach to Rangoon, my Yangon Airways flight pitching violently up and down. The Burmese being fatalists, the pilot skidded us right in. Before I reached the hotel, the rain had doubled in weight. It was April 30.

That afternoon, in a crushing and continuous downpour, the downtown business district was the first to go. Indian and Chinese shops backfilled with water. Intersections became lakes, sewers spilled over, trash spun in the wakes of cars. Then the side streets began to back up. The huge generators on the sidewalks snuffed out, one by one.

The next morning, May 1, a taxi took me to an interview with a final Western diplomat. She’d just returned from Mandalay and had a patch of sunburn on her nose. Over coffee in an old colonial hotel, she confessed to being in love with the country, the desperate strength of the people, the dignity of an ancient culture undiluted by mass tourism, unbroken by repression. But the frightened and clumsy regime was getting more brutal by the month. The most recent development, she said, was the appearance of organized pro-government mobs, called Swan Arr Shin, or “Capable Strongmen,” who had attacked followers of the Lady. People had been arrested for blogging about politics, forwarding e-mail attachments of antigovernment posters, and even writing a Valentine’s Day poem that included the words “crazy with power.”

She hadn’t heard anything about the baffling weather—it used to rain this way “in the old days,” her Burmese staff had told her.

Leaving the hotel, I made the mistake of heading for the post office. Moving north as the rain came pelting down, I hitched up my trousers and joined a ragged column of wet Burmese wading along. At General Aung San Road, there was only a river. Rolling up my pants was useless—even with a poncho I was streaming wet. Out in the avenue, poked by umbrellas, dodging pushed rickshaws and the SUVs of the rich, feeling my way knee-deep in rushing brown water for the broken asphalt underneath, I gave up and turned around. I went back, to a drier part of town, hunted for a taxi, and began leaving Burma.

When I asked the driver why it was raining so hard, he said the Thingyan water festival must have been “auspicious.” We were getting our forecasts from the wrong sources. We passed the forlorn zoo, many of its animals deported to Naypyidaw, and the empty ministry buildings whose people had gone the same way. There was a tree blown down in Pyay Road and cars stalled in the floods. On the balcony of my hotel, I watched the rain bucket down, harder than ever, and the wind smash a thousand palm trees together on the fringes of Inya Lake.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s house-prison was over there, hidden. I’d studied Google Earth views, to see if there was a way to get around the lakeshore to see the Lady; I’d walked the edges of the frozen area around her house, staring up at high walls, topped with both barbed wire and razor wire. Jumping the wall here was the dangerous thing the astrologer had green-lighted for May 1. But the Lady remained out of reach.

There were reports later that she’d lost part of her roof in the storm but, without a choice, had simply ridden Cyclone Nargis out. Sometimes there is nothing to do but survive.

The Aftermath of Cyclone Nargis

There’s a joke that Mandalay comedy troupe the Moustache Brothers tell about the tsunami of 2004. For once, Burma was spared, and the joke is about why. Three corrupt Burmese generals die and for their crimes are reborn as lowly fish. When they see the deadly wave coming, they tell it to turn back from Burma: “We already ruined it.”

Two weeks after Cyclone Nargis, I got an e-mail from the sunburned diplomat. “Somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000” had died, she wrote. She’d spent 15 days trying to organize relief efforts. There were more than 200,000 survivors at that point still in dire need of aid, and maybe 1.5 million more were affected—numbers that would swell to more than 2 million. Plagues were coming.

In another country, like Thailand, there would have been deaths as well. But there would also have been roads, bridges, emergency services, houses of cement, a measure of accountability, and information about the coming storm. In Burma, the generals guaranteed that there was virtually none of that.

Burmese citizens who tried to distribute aid had their cars impounded; refugees waiting for help along the few roads were scolded by the army for daring to beg. It took UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon two weeks to get any Burmese leader on the phone. Weeks into the disaster, the junta finally allowed him to visit Naypyidaw; he returned with clenched teeth to announce “progress.” Aid flights did eventually begin to flow in large numbers—the U.S. delivered water containers for some 187,000 people and plastic sheeting for almost two million, purification equipment and medical supplies, ten Zodiacs for navigating the delta, and 75,000 mosquito nets. But at first, most aid went no farther than the Rangoon region, and NGOs claimed that the military stole some of the best supplies for itself. Many people were forced to go back to their destroyed villages with only a piece of that American plastic sheeting and a stick to hold up their new “tent.” The government told people to be “self-reliant” and eat frogs.

The people I met in Burma all survived, it seems. The barefoot diplomat talked to newspapers worldwide under her own name. The Moustache Brothers tried to hold a fundraising concert for victims but were rebuffed for their cracks about the generals; another comedian, called Zarganar, was arrested for distributing aid. Ma Thanegi e-mailed that even the generals could not keep the crescendo of bad news at bay.

She underestimated them. After weeks of hiding, Than Shwe finally appeared, once, to stroll through a “show camp” for refugees near Rangoon, where he announced that relief efforts were now over.

When foreign donors produced $150 million in funding for relief projects, Than Shwe demanded $11 billion. It would be farce if it were not so cruel.

The Burmese merely suffered. An NGO contact wrote that the generals have “holes where their hearts should be” and described a Rangoon taxi driver angrily demanding an invasion by “Britain or Germany,” since the UN would do nothing. A Burmese contact said that Britain and the United States should arm the ethnic insurgents in remote corners of Burma so they could blast the generals out of power. French foreign minister Bernard Kouchner, a founder of Doctors Without Borders, briefly called for a forced entry to deliver relief supplies, but realpolitik soon asserted itself and the U.S. and French warships sailed away. For their own reasons, China and the nations of Southeast Asia insisted on “non-interference” in Burma’s internal affairs. The junta went ahead with the May 10 election in most parts of the country, evicting refugees from schools and temples to create polling stations. And as I write, a month after Cyclone Nargis, the generals have announced the one statistic they care about: Exactly 92.48 percent of Burma’s cowed and beaten voters chose to keep the iron fist.

The cyclone should have blown down this house of Tarot cards. Maybe it still will. The only effective internal relief force in Burma was the monks, who led truck convoys into the delta and sheltered, fed, and consoled the victims of Nargis at village temples all over the devastated area, claiming their unambiguous position as the real leadership of Burma. Another attempt at a Saffron Revolution, a louder, angrier, and more desperate uprising, seems inevitable in time.

For today, the generals are getting away with it, again. As Alan Rabinowitz told me before the storm, “They couldn’t care less what the U.S. or the West does or doesn’t do.”

In that sense, San-Zarni Bo was right. I got out of Hell on the first of May. It must have been my lucky day.