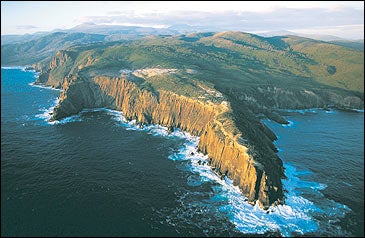

Hazardous coastline: Wineglass Bay in Freycinet National Park

Hazardous coastline: Wineglass Bay in Freycinet National Park Tasmanian devil, mid-hiss

Tasmanian devil, mid-hiss On the rocks of the Freycinet Peninsula

On the rocks of the Freycinet Peninsula

ON ONE OF TASMANIA’S remotest beaches, I was awakened by the screams of devils in the night—a sound that was, in the sinister words of Tassie novelist Richard Flanagan, “like that of a woman being strangled.” Personally, I thought they sounded more like hissing vampires. Perhaps I’d been reading too much about Tassie’s 19th-century colonial days, when the island was settled as a British penal colony and the convicts thought these marsupials were tormented souls in the bush. To calm my imagination, I fumbled for a flashlight and staggered out of my canvas tent into the night: There was nothing to see but the empty, ominous scrub, rustling in the damp sea wind.

The next morning, as I continued on my 18-mile hike along the island’s northeastern coast, my nightmares evaporated in the warm South Pacific sun. Beach after beach stretched into the distance. The sand was paper white; giant round boulders, covered in a scaly orange lichen called xanthoria, glistened like salmon roe all along the virgin shore; the horizon sparkled an indigo blue.

Tasmania’s past is so outrageously gothic that it was hard to reconcile with the candy-bright pageant before me. Tortured convicts would escape their chain gangs and plan to walk to China, I hazily recalled; many got lost in the wilderness and turned into cannibals. Most of Tasmania’s landscape suits its history: wild, wet, fungal, and mountainous, battered by gales and shrouded in bone-chilling mist. At night, you can sense the ghosts just outside the tent flaps. But come dawn, the haunted shore looks suspiciously like paradise—Tahiti with eucalyptus trees, suffused with piercing light. This helps explain why the recently inaugurated Bay of Fires Walk—named after the most spectacular of the many coves on this forgotten coastline—has become the hot ticket for nature lovers from mainland Australia. I was hiking with nine urban Aussies, guided by a pair of feisty Tasmanian country girls in their twenties. On the four-day excursion, we would follow the surf line for almost 20 miles through 34,345-acre Mount William National Park, the least visited refuge in the least visited Australian state, spending the first night in a canvas-covered beach tent and the last two in the luxurious Bay of Fires Lodge.

Remoteness has long been Tasmania’s trademark, and these days obscurity is quite a PR boon. Tassie is one of the few places on earth to report an increase in travelers after 9/11. “We’re safe, we’re clean, we’re a hell of a long way from anywhere else,” one local shrugged. (Statistics are charmingly vague, but foreign arrivals appear to increase by about 25 percent every year.)

Tasmania’s mystique has been ingrained since birth in wandering Aussies like myself. Years ago, I took a month to hitch around the apple-shaped island, hiking into remote national parks with a sleeping bag under one arm and a bag of white rice under the other. This time, flying from New York to Launceston, I eased myself into Tassie in a slightly less haphazard way: Interlopers from the outside world are now offered rustic luxury within their bush jaunts, and even the most far-flung pockets of Tasmania have their lonely wilderness lodges, where visitors can enjoy a little haute cuisine.

These civilized oases were almost impossible to imagine when our group first set off on the Bay of Fires trail, beginning at Stumpys Bay, where a dirt road from Launceston had petered out a stone’s throw from the surf. As we hiked into the void, the fall temperatures were in the mid-sixties, warm enough for shorts and a T-shirt. The pace along wet sand provided a decent workout, and with the sweat beginning to pour, I already had the feeling that I’d stumbled into the wrong latitude. But when I threw off my pack and plunged into the waves, there was no doubt this was the deep antipodes. It was like jumping into iced sake.

“There are currents coming from both the north and the south,” explained Natalya, a wiry Argentine-Tasmanian fresh from the dairy farm, who had just taken up guiding at age 22. “This one’s out of Antarctica, I reckon.”

We stared out at the waves, tasting a sudden rawness in the wind. The purity of this coastline was almost lacerating; I felt like I was being stone-washed clean. Then, before dusk, we stumbled into the first wilderness refuge, the Forester Beach Camp—a semi-permanent, steel-framed canvas tent with a few humble luxuries, like foam mattresses for the sleeping bags and certain exotic camping foods, 100 yards off the beach. Tassie tucker, once a grisly menu of English boarding-school sludge, would now satisfy any French provincial gourmand: organic double-cream brie, chèvre, salmon. Not to mention a constant supply of Tassie “plonk”—red wine.

“The pinot noir is a particularly good drop,” Amy, the other guide, said proudly.

The sense of privilege grew even deeper the next morning as we continued along what naturalists sometimes refer to as “the spray zone,” a stretch of unique shoreline vegetation in contact with the saltwater spray. Biologically alien items had washed ashore—purple “sea eggs,” seaweed bulbs as delicate as Faberge eggs; and the long strands of bleached white sponge known as “dead men’s fingers.” I took off my shoes to follow the tightly packed sand along the surf line. A string of islands stretched along the horizon, last relics of a land bridge crossing Bass Strait, an isthmus that once linked Tasmania to the mainland. It flooded after the Great Ice Age, 8,000 to 12,000 years ago, sending every plant and animal on a unique evolutionary trajectory.

In the late afternoon, we descended a rocky headland called Eddystone Point onto the Bay of Fires itself—the most perfect of the beaches, three miles of exquisitely unblemished sand. The bay was named in 1773, when the British sea captain Tobias Furneaux, passing by in a ship, saw campfires blazing in the bush. They had been lit by the Tasmanian Aboriginal people, whose ancestors are believed to have crossed over from the mainland about 30,000 years ago and gotten isolated when the land bridge was flooded. They were hunted by British settlers like foxes in a calculated campaign of extermination, and by 1878 the last full-blooded Aboriginal was dead. Now, their pyramid-shaped middens, or mussel-shell dumps, stand along the coastline like memorial cairns.

“Behold the promised land!” crowed Angus, a former surfie from Melbourne, as we ascended Bayley Hummock and spotted a man-made structure almost entirely lost in the forest. We slipped into a sleek structure composed of Tasmanian hardwood and glass, perched above the beach, whose simple architectural lines and expansive walls of glass revealed the riotous bush and blue horizon at every turn. The Bay of Fires Lodge was designed with the purest of eco-intentions: The power is solar, the toilets are dry-compost, and rainwater is collected for the showers. But there’s no stinting in the alcoholic beverage department: Young Angus had already poured his first glass of Tassie sauvignon blanc as we surveyed the 270-degree sweep of the ocean from the lodge’s deck—and spotted the spout of a southern right whale rising in the distance.

After two days at the lodge, I’d kayaked a sinuous bush river and skimmed across the placid bay racing eagle rays. I’d relished blue-eyed cod in chile-lime sauce, prepared by the guides. I’d even managed to bodysurf those glassy rollers. (Surfing, however, was out of the question, as it would have required hauling a board on my back for 20 miles. Plus, the best waves in Tasmania are south of the Bay of Fires near the town of Bicheno.)

Thawing out on the sun-filled terrace with a final eggs Benedict, I had to admit: The Bay of Fires Walk had been brilliant, but I missed that rush of Tasmanian freedom I used to feel when I was out in the bush alone, with no coherent plan. So back in Launceston, I dashed into a camping store, picked up a tent and sleeping bag, jumped in a rental car, and started driving.

It was time to set up my own private eco-lodge.

As I drove due south, then swung back to the east coast, the Irish-green farmland began to unravel and finally dry to a salty brown. I took the turnoff to Freycinet Peninsula, a dinosaur spine of granite above a string of secret coves about 80 miles south of the Bay of Fires, and climbed a crest to view Wineglass Bay. At the far end of the beach, I found the best campsite in Tasmania. There were three Norwegians in one tent, and a couple of Aussies in a recess, but the natural seclusion was palpable. In fact, we all gathered to watch the sun setting over the peaks—called the Hazards—then admired the stars, joined by a Tasmanian yachtsman who’d weighed anchor in the bay for the night.

Admittedly, my camping grub wasn’t exactly gourmet—I’d brought a pastrami sandwich with me from a Launceston deli. The possums devoured my breakfast, which I’d strung up between two trees. And then it started to pour down rain, so I trudged back to my car like some wild-eyed prophet, taunted by the laughing kookaburras as I passed them. But I’d proven one thing: No matter how much pinot noir or double-cream brie it produces, Tasmania hasn’t been tamed quite yet.

ACCESS AND RESOURCES

FOR MOST OF ITS HISTORY, Tasmania has been dismissed as a Faulkner-meets-the-antipodes backwater, the lost domain of hillbillies and sheep molesters, and the sort of place mapmakers forgot to include on their charts. Until the 1980s, that is, when a string of conservation campaigns publicized Tassie as Australia’s ultimate natural escape—an Eden for “greenies.” Now everyone wants a piece of the isolation. Thanks in part to the centuries of neglect, the island is still empty and raw. Imagine the Scottish moors with temperate rainforests and sinuous rivers, and you have Tasmania. Mountain ranges furrow the land like ancient wrinkles. Hundred-foot trees create dark empires of rotting foliage. Rivers run with water the color of tea. Luscious ferns blot out the sky. And the underpopulation is extreme even by Australian standards: Only 470,000 Tasmanians occupy an area the size of West Virginia (195,000 of them in the capital, Hobart), with about a quarter of the island marked as protected land.

Getting There

Qantas Airways flies to Hobart, Devonport, and Launceston (800-227-4500; )—but nobody comes to Tasmania for the city life. Instead, rent a car and seek out the unpaved roads and some of the world’s last great wilderness areas.

The Best of the Backcountry

BAY OF FIRES WALK: This 20-mile trek runs along the beaches of Mount William National Park, at the island’s northeastern tip. Thanks to the weak Aussie dollar, the all-inclusive cost for four days of hiking is US$770 (Down Under Answers, 800-788-6685, ; for more information on the hike itself, check out ). To go solo, rent camping gear in Launceston from Paddy-Pallin ().

FREYCINET NATIONAL PARK: Eighty miles south is the stunning Freycinet National Park, where jagged peaks, known as the Hazards, rise over a string of brilliant white beaches. A steep unnamed trail leads over the granite saddle to a secluded campsite at Wineglass Bay, then continues on a 19-mile circuit around the peninsula. Camp on your own or go the cushy route, sleeping in low-impact bush huts (four-day guided trip by Freycinet Experience, $760; ). The protected western flank of the peninsula is also ideal for kayaking: Freycinet �����ԹϺ���s runs three-day kayak excursions ($390; ).

THE OVERLAND TRACK: Tasmania’s most famous bush walk, the 50-mile Overland Track winds through Cradle MountainÐLake St. Clair National Park, in the alpine heart of the island. For six demanding days, hikers wend their way over windswept highlands riddled with streams and dotted with swimming-pool-sized glacial lakes that glisten like black pearls. Public huts with gas heaters and bunk beds have been set up for hikers among the crags, but carry your own tent, since they are first-come, first-served. The easier option is to go with the outfitter Cradle Huts ($1,000, ), which maintains its own custom bush huts along the route, stocked with food. Beyond Cradle Mountain, the sprawling, inhospitable region referred to bluntly as the Southwest is Tasmania’s—and possibly the world’s—ultimate wilderness area, a mind-boggling expanse of 3.7 million acres covered with temperate rainforest, whose rarely trod depths support groves of thousand-year-old trees.

THE FRANKLIN RIVER: Carving its way through the Southwest’s pristine wilds, the Class IIIÐIV Franklin River remains a rite of passage for whitewater rafters. This ten-day trip passes beneath the red-lichen-covered quartzite cliffs of Blush Rock Falls. The dark waters are home to platypuses, snakes, and freshwater lobsters. It’s a notoriously tricky run, so go with a reputable operator (Rafting Tasmania, , offers trips for $1,095).

THE SOUTH COAST TRACK: The true end of the line—a nine-day odyssey along muddy trails that cling to the final extremity of Australia. The intrepid arrive by light aircraft in Melaleuca, then slog their way for 50 miles along cliffs, flooded rivers, and shifting beaches. The payoff is the sense of utter removal: It’s just you and the Pacific gulls. ($815, Tasmanian Expeditions, ).