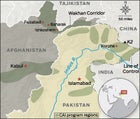

Map

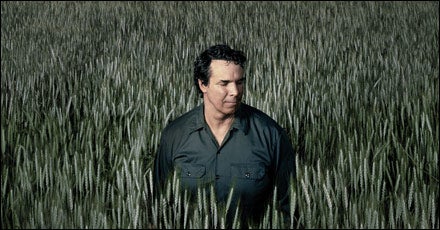

Greg Mortenson

You listen with humility: CAI's approach to school-building is shaped by Mortenson's extensive travels in Pakistan and Afghanistan

You listen with humility: CAI's approach to school-building is shaped by Mortenson's extensive travels in Pakistan and AfghanistanTHE HABIB BANK OCCUPIES a four-story building in Kabul’s Shahr-i-Nau district, a neighborhood that features an outdoor photo exhibit of Afghan land-mine amputees, an Internet café that was blown up by a suicide bomber in 2005, and a man holding a trained monkey on a chain. At five minutes to nine on a Saturday morning, the monkey’s eyes dart toward the bank’s entrance as two men in combat vests come charging out through the doors.

The figure in front, a hulking six-foot-four American, is wearing a pair of size-15 Merrell clogs and a shalwar kameez, the pajama-style robes favored by men throughout Afghanistan. Behind him is a former Pakistani commando whose right hand is frozen into a kind of claw. In it, he clutches a plastic bag just given to him by the lady who brings fresh-baked bread to the bank’s employees every morning. The bag now holds 23 bricks of cash totaling $100,000. The cash is dusted with flour, and both men are running as if the devil himself were after them.

They jump into a cab that plunges into the morning traffic, speeding past tea shops and Indian video stores and into the Wazir Akbar Khan roundabout, where the driver unwisely opts for a shortcut that involves entering the thing in the wrong direction.

Oops.

A policeman blocks the vehicle and slams his fists on the hood. Then he reaches through the open window and starts shaking the driver by his lapels while unleashing a blast of enraged Dari, the language spoken throughout half of Afghanistan. From the backseat, the retired commando calmly vise-grips the driver’s neck and barks a one-word command: “Burro!”

Rough translation: “Floor it.”

The driver rams the accelerator, leaving the cop kicking the side of the cab as it resumes its race toward Kabul International Airport, where the men’s plane was scheduled to start boarding at 8:40 a.m.

“Hey, what time is it?” the American wonders as he stuffs cash into his vest.

“Nine-o-five,” the Pakistani grunts. “Too bad we cannot ring up Mr. Siddiqqi.”

Mr. Siddiqqi would be a big help right now. He ran the control tower at Kabul’s airport for 38 yearsa period spanning the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, from 1979 to 1989; the anarchic civil war that followed; and the country’s seven-year imprisonment under the Taliban, from 1996 until the U.S.-led invasion following September 11. Back then, anyone who had taken the trouble to pay a visit to the tower and have a cup of tea with Siddiqqi needed only to give him a ring if they were running late, and he’d hold their plane. Unfortunately, Siddiqqi’s recent retirement has now created the possibility of something unthinkable.

“We’re about to miss this plane,” the American mutters. “You know, we should probably call and find out”

“what Wakil is up to?” says the Pakistani, completing the thought. He punches the cell-phone code for Wakil Karimi, their Pashtun accomplice in this morning’s operation. Three seconds into Wakil’s woefully unacceptable report, the Pakistani’s face darkens with anger.

“What the hell are you doing sitting down drinking chai?! This is not an episode from Three Cups of Tea! Get your butt outside the airportnow!”

As the taxi weaves through donkey carts and battered minivans, the shouting continues. “Have our tickets ready! Have a porter standing by! Tell security to let us through!”

The men brace as the cab screeches to a stop at the airport entrance, and there stands poor Wakil, with his Areeba flip unit glued to his ear, enduring the novel misery of finding himself excoriated in person and over the phone at the same time.

“You know, some people say that we’re just totally winging things over here in this part of the world, but that’s not really fair,” the American remarks, somewhat defensively, as he shuffles toward the gate, where it is now being announced that the flight has been delayed for three hours.

Before completing the arc of an argument whose abundant illogic has escaped his notice, he pats his pockets to make sure he hasn’t dropped a stray wad of cash that will cover the annual salaries of 20 schoolteachers working in the mountains of northern Afghanistan.

“It’s true, of course, that back in the early days we may have been flying by the seat of our pants a bit. But, believe me, we are much more organized now.”

THE PROVENANCE OF THAT hundred thousand dollars, which was assembled through small and large donations from every corner of the U.S., was as diverse as America itself. It had come from Muslims and Hindus, Christians and Jews, Buddhists and atheists, and maybe even a Wiccan or two. Some of it was sent by a Baptist youth group in Alabama; some came from a North Carolina chapter of Future Teachers of America; and some was a gift from veterans of the 82nd Airborne Division. From Massachusetts, a 12-year-old girl named Gabby contributed $50 that she’d earned babysitting. Lorraine, a single mother from Simi Valley, California, sent in a box of pennies worth $7.47, followed later by a check for $25. From San Diego, an 82-year-old woman named Hannah, retired and living on a shoestring, wrote to say she wanted to help with what little she could spare. She gave $100.

Regardless of where the money originated, all of it had been funneled through a three-story office building at the east end of Main Street in Bozeman, Montana, the headquarters of the Central Asia Institute (CAI), an operation created to honor a promise made in 1993. That was the year Greg Mortensonthe fellow now catching his breath inside the converted shipping container that serves as our departure lounge inside the Kabul airportattempted to climb K2, the world’s second-highest mountain. He did so while wearing a shalwar kameez, taking on this killer peak with a group of 12 underequipped climbers who were known as the Rejects.

Mortenson had launched the climb in memory of his younger sister Christa, who’d suffered from epilepsy and had died of a seizure on her 23rd birthday. After exhausting himself by taking part in the successful high-altitude rescue of another climber, he was forced to turn back 2,000 feet shy of the summit. Then, while trekking down the 39-mile Baltoro Glacier, Mortenson got separated from his Balti porter and wound up staggering into a village called Korphe, a place so destitute that roughly one in every three children perished before the age of one. It was in Korphe that he was offered shelter, food, tea, and a bed. And it was in Korphe, one afternoon during his recuperation, that he came across 82 children sitting outside writing their school lessons with sticks in the dirtwith no teacher in sight. One of them was a girl named Chocho, who made Mortenson promise to come back someday and build them a school.

The fulfillment of that pledgethe subsequent chain of events through which a lost mountaineer found his life’s calling by promoting literacy in the impoverished Muslim villages of the eastern Himalayasis a story that, by now, a lot of people have heard. Two years ago, with the help of co-author David Oliver Relin, Mortenson, now 50, laid out his unusual saga in Three Cups of Tea, a book that tells the tale of how he sold his car and his climbing gear and started raising money for schoolsliterally one cent at a time, beginning with a school in Wisconsin where the kids filled two 40-gallon trash cans with 62,345 pennies.

When the book was published, in March 2006, it debuted at number 14 on The New York Times‘ nonfiction bestseller list before dropping off. Then, starting last year, sales began to explode. Driven by a surge of interest from women’s book clubs and churches, the book climbed to the top of the paperback list, where at press time it had spent more than 27 weeks at number one. As of October, Three Cups of Tea had sold 2.1 million copies, been printed in 19 languages, and spawned a sequeldue out next fallthat will complete the dirtbag-to-rock-star chronicle of a mountaineer who, by all reasonable expectations, could easily still be living out of the back of his car.

In the 15 years since his Korphe experience, Mortenson has made 37 trips to Pakistan and Afghanistan, logging nearly 250,000 air miles a year while organizing the construction of 78 schools that currently serve some 28,000 students. He’s also put together graduate-scholarship and teacher-training programs, paid to build women’s vocational centers, and underwritten water-purification projects. He has probably spent more time, traveled more miles, and come to know the region more deeply than any diplomat, soldier, academic, or aid worker in America.”Greg is my hero,” says newsman Tom Brokaw, who donated $100 in 1994, in response to a hand-typed letter from Mortenson that hundreds of other prominent recipients ignored. “This gentle but determined young man is winning hearts and minds one school at a time, in a part of the world where we rely too much on the military response and not enough on the humanitarian and social approach.”

As Three Cups of Tea‘s success continues, the Mortenson juggernaut shows no sign of letting up. In the past year, he’s made roughly 150 appearances in more than 100 U.S. cities, sharing his story with crowds of up to 20,000a big change for a man whose slide shows, until just a few years ago, drew only half a dozen bored shoppers at REI and Patagonia stores. The CAI’s gross intake has grown from $480,000 in 2002 to nearly $4 million last year. These days, tickets to Mortenson’s presentations sell out within hours, hosts often have to book a second venue, and most speaking requests must be made a year in advance.

“The irony is that we’re actually trying to slow down our growth,” says Mortenson, who has the weary look of a bear in serious need of hibernation. “Yet the harder we try, the faster it seems to grow.”

Through it all, Mortenson has struck a chord with groups that don’t usually see eye to eye. In addition to speaking before Rotary clubs, in public libraries, and at college commencements, he has appeared at Islamic schools in Chicago, at a synagogue in New York City, and before a group of lesbian activists in Marin County.

And then there’s the U.S. military, currently in its seventh year of deployment in Afghanistan, where coalition casualties started exceeding those suffered in Iraq last May. In November, Mortensonwho served as an Army medic from 1975 to 1977was asked to share his views about Pakistan and Afghanistan with General David Petraeus, whose focus on building relationships with local communities dovetails with the CAI’s approach. Sometime this winter, Mortenson is slated to do the same with the office of Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He has lectured at Annapolis, West Point, and the Air Force Academy. Three Cups of Tea is now recommended reading for officers enrolled in graduate-level counterterrorism courses in the Army, Navy, and Marines.

Mortenson is also widely respected overseasrare for an American these days. He has given presentations in several countries, including Sweden, Tanzania, and the United Arab Emirates. Pennies for Peace, an offshoot of the original Wisconsin piggy-bank drive, now has programs running in Europe, Asia, and South America. Last year, it was picked up in South Korea, China, and Rwanda.

Mortenson’s visibility, however, has put him in the crosshairs of extremists and crackpots. In Pakistan, two religious clerics issued fatwas (since rescinded) calling for his expulsion. In August 1996, he was kidnapped in Waziristan and held for eight days before being released. Earlier this year, a CAI school in Afghanistan was attacked by the Taliban.

There have been some nasty reactions at home, too. “In the U.S., I get quite a bit of hate mail and criticism,” Mortenson says. “People have attacked me for working with Muslims, for acting like a colonialist, for being a traitor to America. But we continue to operate, because we have fierce local support. The communities we work in will do anything for education, and as long as they want schools, our mission is to provide them.”

THREE HOURS AFTER RUSHING to the airport, we finally board a 12-seat twin-turboprop Beechcraft and lift off over the brown expanse of Kabul. The plane is operated by PACTEC, a nonprofit that shuttles humanitarian workers around Afghanistan. PACTEC offers no beverage service, but the seat pocket does contain a laminated guide to avoiding land mines, which still kill or maim around 65 Afghan civilians every month. As the Beechcraft arrows toward Badakhshan, Afghanistan’s northeasternmost province, we gaze east toward the 19,000-foot peaks guarding the approaches to the Pakistani region of Baltistan, where Mortenson forged the ideas that define his mission.Ever since Islam was brought into the Baltistan area by itinerant Muslim sheiks in the 15th century, the privilege of learning to read and write has, in many mountain communities, been reserved for males. Like most experts, Mortenson is convinced that educating girls is the most important step in reducing infant mortality and bringing down birth rateswhich in turn helps fight the ignorance and poverty that often nurture religious or ethnic intolerance. Thus every new school the CAI funds must provide access to girls.

“Once you educate the boys, they tend to leave the villages and search for work,” says Mortenson, who spent most of his boyhood in East Africa, where his parentsLutherans from Minnesotabuilt Tanzania’s first teaching hospital, in the shadow of Kilimanjaro. “But the girls stay home, become leaders in the community, and pass on what they’ve learned. If you really want to improve quality of life, the answer is to empower the women by educating the girls.”The importance of girls’ education is widely recognized around the world. CAI’s special twist is the amount of time and effort Mortenson spends selling the concept on the ground. His guiding philosophy is summed up in his book’s title, which refers to a saying he heard in Korphe. “The first cup of tea you share with us, you are a stranger,” it goes. “The second cup, you are a friend. But with the third cup, you become familyand for our families we are willing to do anything, even die.”

“In order to get things done, it’s necessary to listen with humility to what others are asking for and what they have to say,” says Mortenson. “The solution to every problem over here begins with drinking tea.”

This might sound simplistic, but the results are impossible to dispute. Down inside the narrow mountain valleys that lie veined far below the Beechcraftwhere more than 400 villages are now clamoring for a schoolthe first crop of CAI-educated women are preparing to launch their careers. Jahan Ali, 21, the granddaughter of the headman of Korphe, graduated in 2002 and is studying developmental planning in Skardu. She plans to go into politics. Shakila Khan, 21, graduated with the first class in Hushe School and is finishing her third year of medical school in Lahore. She will be the first female physician to emerge from an area of the country that harbors 1.2 million people.

“You could say that those women down there are making first ascents far more dramatic than those of the Western climbers who came into these mountains 30 or 40 years ago,” says Mortenson, who next March will receive the Sitara-e-Pakistan, Pakistan’s highest civilian award, which is almost never given to a foreigner. “They will have a far greater impact than the statistics buried inside the pages of The American Alpine Journal.”

True enough. And yet it was the sport of mountaineeringthe strength of will it demands, the maverick impulses it can nurture and shapethat first inspired Mortenson’s radically unorthodox approach to building schools. Pointing through the plane’s window at the distant summit of Noshaq, at 24,581 feet the highest peak in Afghanistan, he explains the overall blueprint.”If you look at a map,” he says, “you’ll see that our schools are all in isolated pockets that have no educational infrastructure due to remoteness, poverty, religious extremism, or war. These are the areas where nobody else goesand, basically, what we do is start at the end of the road and work our way back. We don’t want to build thousands of schools. We just want to put a few into the hardest places of all, then hope that the government or other NGOs will start moving toward us.”

The strategy has worked well in Pakistan, where Mortenson’s staff spent the late nineties target=ing the farthest-flung villages in the most remote valleys. In 1999, at the request of the Pakistani military, they launched projects in the Gultori region, where the armies of India and Pakistan were locked in fierce fighting along the Line of Control, which defines Kashmir’s contested border. The schools they put in, which were tucked into the mouths of caves, featured sloped roofs that can deflect rockslides triggered by artillery shells. That fall, they also started working with contacts in Afghanistanan effort spearheaded by the broken-handed man now sitting in the back of the Beechcraft, whom Mortenson likes to call “our Indiana Jones.”

This is Sarfraz Khan, 53, who was shot through the wrist during a gun battle with the Indian army in 1974. After his military discharge, Sarfraz started plying the snow-covered passes that connect his home in Pakistan’s Chapursan Valley to the Wakhan Corridor, a narrow finger of Afghanistan, 200 miles long, that thrusts between Tajikistan and Pakistan all the way to China. Three or four times a year, Sarfraz would haul flour, sugar, and tea into the Wakhanan area almost completely cut off from the outside worldand return with yaks and goats. The work helped create a unique skill set: He knew the terrain; he knew the people along the border; and he had a superb grasp of the local languagesall seven of them.

Mortenson met Sarfraz in 1999 and, the next year, dispatched him to survey the Wakhan’s infrastructure. Sarfraz found that after nearly three decades of war, there was barely a skilled mason or carpenter left in the corridor. His solution was to import teams of Pakistani craftsmen. With permission from the border police, he started escorting groups of 20 workers at a time over the passes without visas or passports. Every few weeks, he would return to monitor progress and pay the men with money he carried in saddlebags. He set such a relentless pace that at the end of one trip, upon reaching the far side of the pass, his horse fell to the ground and died.

By the summer of 2008, the CAI had built nine Wakhan schools, with five more in the works. Our current visit will include a typical mix of ribbon-cutting ceremonies, bill paying, and meetings to discuss new projects. The plan is to land in the provincial capital of Faizabad, then head east until we reach the end of the road, at the village of Sarhad.

That’s the scheduled itinerary, anyway. With Mortenson, there are always surprises, and the first arrives as our plane taxis to a stop and the copilot turns to face the passengers.”Welcome to Badakhshan,” he announces. “Whichever one of you guys has got the armed escort, they’re headed this way.”

EVEN BY THE EXTREME standards of Afghanistana country where a majority of the population has never known peace and the average life expectancy is 43 yearsthe province of Badakhshan, which contains the Wakhan Corridor, is a rough place. One telling measure is the number of women who die during pregnancy. In the U.S., the rate is 11 per 100,000. In Afghanistan, it soars to 1,800, and the situation in Badakhshan is as bad as anywhere in the country.

It’s also the only part of Afghanistan that was never conquered by the Taliban. Credit for that goes to some exceptionally tough local mujahedeen commanders, one of whom has just surrounded our plane with a dozen heavily armed men and several pickup trucks. Wohid Khan, 52, has dense black eyebrows and a precisely razored beard that’s just starting to turn gray. He started fighting the Russians at age 22; these days he’s in charge of border security in the eastern part of the province. Khan and 250 men patrol 840 miles of rugged terrain where the Wakhan shares a border with Pakistan, Tajikistan, and China. This is one of the most heavily trafficked heroin routes in the world, as well as a popular thoroughfare for gunrunners.

Like many mujahedeen whose schooling was cut short by war, Khan sees education as the key to reversing Afghanistan’s devastationwhich is why he has given his full support to Mortenson’s projects. The father of several daughters, he’s especially passionate about building schools for girls. As a gesture of respect, Khan will provide Mortenson with a high-speed escort in three Ford Ranger pickups, rigs that carry shoulder-held rocket launchers and a .50-caliber machine gun mounted to a tripod.

We roar out of Faizabad, with three soldiers perched in the back of each truck, their Kalashnikovs between their knees. As we barrel along on unpaved roads, Mortenson explains that this is not his standard mode of travel.

“When Sarfraz and I come into the Wakhan, we’re usually in a beat-up jeep or a minivan that we’ve hired, and we’re constantly switching drivers to avoid getting ambushed or kidnapped,” he says. Sarfraz also switches up languages while concocting elaborate lies about who they are and where they’re going.

“When I’m worried, there is no stopping, no eating, no drinking,” Sarfraz says. “Greg’s life is very important to me.”

Traveling with Wohid Khan is different: Since he’s the local strongman, the only thing you have to worry about is hanging on. Khan’s drivers are under orders to push their rigs to the maximum speeds that the shattered roads allow40 to 50 miles per hour. Moving fast is standard procedure, because the border-security force handles all sorts of problems over a huge area. Two weeks ago, a car transporting two teachers, both of their wives, and four children to a new CAI school in the village of Buzzai Gumbad accidentally shot off the road into the Amu Darya River. The driver and one of the families were drowned. The other family spent the night balanced on the roof of the car. Khan and his team raced to them the next morning and pulled the survivors to safety.

Khan can be quite ruthless about keeping these roads open, which is crucial for the flow of food supplies to the region. This becomes evident one afternoon when we encounter a truck that has obstructed traffic by stopping in the middle of the throughway. The commander gets out and walks up to a man who’s working on a broken rear wheel.

“Driver or mechanic?” he asks.

“Driver,” the man replies.

Khan smashes his fist into the man’s face, then kicks him in the stomach, twice. He gets back in the Ranger and we resume our journey.

“People criticize me for working with so-called warlords,” says Mortenson, “but sometimes you’re forced to choose between working with the resources at hand and not accomplishing anything at all. In the end, it’s all about relationships, and we’re willing to collaborate with almost anyone who shares our commitment to education.”

For the next two days, we bash though dry washes and small villages, pushing deeper into the most obscure corner of Afghanistan. When we reach Baharak, the valley forks in three directions and we head west toward Ishkoshem, a town of 20,000 families. Here, on the morning of our third day out, we come to the jewel of the CAI’s Wakhan program: an unfinished foundation about the size of a football field, filled with dirt, stones, and loose sand, future home of the Ishkoshem Girls’ High School.

The completed structure will be two stories tall and will host 1,200 female students. Costing more than $70,000, it will be the largest school ever built in this region, and it will have one of the most magnificent settings for any school anywhere. To the north loom the Pamir Mountains, painted with the shadows of high clouds, racing across the brown slopes in the lemon-yellow light. To the south are the sharper ridgelines and cliff faces of the Hindu Kush, armored in ice even now, in late July.

More than 100 men are clustered around the school’s foundation; they’ve come from as far away as Kabul to see the cornerstone laid. Off to the side is a group of about 40 girls, several of whom are clad in head-to-toe burkas. They are all waiting to hear Mortenson. After thanking everyone for attending, he offers a short speech, which is translated for the crowd.”This school is your school,” he says. “It is not a gift of the American government but of small people like yourselves, across the United States, all of whom gave small donations so that this school, and others like it, can be built in remote areas where education is needed.”

He glances briefly over at Khan, who listens carefully. “A wise man in this area once told me that these mountains have seen far too much killing, and that each rock you see represents a mujahedeen who died fighting either the Russians or the Taliban. But now that the fighting is finished, it is time to build a new era of peace. And the first step is to take up these stones and start turning them into schools.”

The applause from Khan and his soldiers is especially fierce.

THERE ARE MANY unorthodox aspects to Mortenson’s operation, but perhaps the oddest is his preference for hiring inexperienced, underqualified, often uneducated locals from whom he somehow extracts amazing results.

Take Sarfraz, who manages CAI programs in the Wakhan and Azad Kashmir. “Without Greg, I would be nothing more than a guy who trades yak butter,” he says. But Mortenson seems convinced he got the better end of the deal. “I’ve learned so much from this guythe way he goes into the most rugged areas, unarmed and without fear, to meet with military commanders, warlords, and very shady tribal leaders,” he says. “Sarfraz is constantly moving, he’s culturally savvy, he’s smart and wily, he’s firm when he needs to be. Plus he’s got some humor and some charisma going for him, too. When it really comes down to it, I am a donkey, but Sarfraz is a king.”

Altogether, the CAI’s staff in Pakistan and Afghanistan totals about a dozen men. The roster includes a mountaineering porter, a devout Shiite scholar, a farmer who’s the son of a Balti poet, a taxi driver, a man who grew up in an Afghan refugee camp, a base-camp cook, and two former members of the Taliban. A quarter of them cannot read or write. Crucially, they are evenly divided among the regional subsects of Islam: Sunni, Shia, and Ismaili (a liberal offshoot of the Shia whose majority-recognized spiritual imam, the Aga Khan, is based in Paris).

“If it weren’t for Greg, you probably wouldn’t even find these guys in the same room sharing a cup of tea,” says Genevieve Chabot, part of the CAI’s American staff, “but with little pay and almost no supervision, they’ve somehow found a way to make it work.”

Whenever Mortenson is on the road, he travels with at least two or three of these men at all times. In Pakistan, they spend weeks racing about in the CAI’s battered green Land Cruiser with a box of dynamite stashed under the passenger seatwhere Mortenson usually sitsso they can blast through rockslides and avalanches without having to wait for government road crews. In Afghanistan, they’ll travel for 30 hours at a stretch, pushing vehicles to the point of breakdown. In the spring and fall, they’ll hydroplane through the mudwhich can be three feet deep in the Wakhanuntil the axles get buried. While the drivers schlep off to find a yak team, they take off their shoes, and sometimes their pants, and start walking.

When Mortenson and his men arrive at their destination, the first thing they do isinspect the school, often surrounded by a scrum of children tugging them by the hands. Then they convene with the village heavyweights for a jirga, or council session. Jirgas are solemn gatherings that feature long speeches and dense deliberation; they usually extend through dinner and last long into the night. Toward dawn, Mortenson and company cram into an empty room or bunk down on the floor of the school. Two hours later, the circus packs up and heads off to the next project.

“Sometimes we don’t stop for five or six days,” says Sarfraz. “This is the only way to get to all the projects and to see all the people we need to see.”

“I think of these guys as the Dirty Dozen,” says Mortenson. “Most of them are renegades or misfits, but over the years we’ve empowered them to make a difference in their communities. And in response, they’re now running around doing a job that it would take a dozen organizations to match. It’s hard to explain, but I don’t really do much over here anymore except travel, drink tea, and watch them work. To these men, schools are everything. They would lay down their lives for girls’ education.”

OUR JOURNEY CONFORMS to the pattern of a typical CAI road trip. Each day begins at dawn, when Mortenson and Sarfraz wake up in the same clothes they’ve been wearing for more than a week, surrounded by the clutter of their mobile office. First on the agenda: morning ablutions, which consist of Mortenson smearing hand sanitizer on his face and hair while Sarfraz scratches himself. Then they pop the cap on their jumbo bottle of ibuprofen, and each man selects two or three tablets as a pre-breakfast appetizer. “When we’re going hard, we both go through about 12 or 15 of these things a day,” says Mortenson.

At this point, one of the two men may put on the pair of eyeglasses they share (they have the same prescription) while the other steps outside with the toothbrush. (Yep, they share that, too.) One morning, I ask Mortenson to provide a list of everything else that he and Sarfraz use together.

“OK, let’s see, we share our jackets, our razors, our soap, our socks, our shalwar kameez, our undershirts”

How about underwear? Do they share that?

“Well, no, but ”

Mortenson hesitates, a sign that he may be concealing something. “Look, I’m not sure I want to reveal this, but there’s no sense in lying about it, either. It turns out that I don’t actually wear any underwear. I grew up in Tanzania, see, so I’ve kind of gone ‘alpine style’ for my entire life.”

“What about you, Sarfraz?” I demand.

Sarfraz looks mildly embarrassed. “Alpine style for me, too.”

“But one thing we don’t share,” Mortenson adds helpfully, “is our wives.”

“No, that we definitely do not share,” Sarfraz exclaims. “Wife sharing is a very bad idea!”Although we’re both really afraid of our wives, so I suppose you could say we share our fear,” Mortenson adds.

“Actually,” corrects Sarfraz, “I am afraid of my wife, of course, but I am also afraid of Greg’s wife, too.”

Tara Bishop, lodestar to the intergalactic mess that passes for Mortenson’s life, is the daughter of Barry Bishop, a National Geographic photographer who was part of the first American ascent of Everest, in 1963. Tara met Mortenson in San Francisco in 1995, at an event in which Sir Edmund Hillary spoke about his own school-building efforts in Nepal. A few hours after laying eyes on Mortenson, she announced her intention to “kidnap” him. They were married six days later. Ten days after that, Mortenson flew back to Pakistan to finish building the Korphe school.

Bishop, who has a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, realized that she’d hitched her wagon to an unusual man. (“Greg is simply not one of us,” she likes to say.) But sharing a life with Mortenson has resulted in twists that even she might not have anticipated.

Their modest home in Bozeman lacks a third bedroom, so Mortenson and Bishop sleep in the upstairs hallway. Meanwhile, their daughter, Amira, 12, and their son, Khyber, 8, have been forced to adjust to having a father who’s often absent: Mortenson was away while his kids learned to walk, talk, and ride a bike. But the children have been treated to some exotic family vacations. Amira went to Pakistan for the first time at eight months, and on one special occasion she got a tour of the CAI’s latrine-building projects along the Baltoro Glacier.

When Mortenson’s on the road, Bishop keeps close tabs on him, dialing Sarfraz’s satellite phone every day or two as we move from village to village, where Mortenson is barraged by requests for assistance. In a place called Khun Dhud, there’s a man who wants money to set up a grocery store. In Ishkoshem, a pair of officials seek funds for a water-delivery system, while another is hoping for a hydroelectric plant. In Pigiz, the school principal needs desks and filing cabinets. The pleading is always polite, but the needs are endless: more books, more pencils, more uniforms, another school.

“We get proposal after proposal, and we have to say no to dozens of projects,” Mortenson sighs one evening, while hearing a request from a group of local women who want him to pay for a new vocational center, where they’d be able to sew clothing and crafts to sell in the village bazaar. “Some of these people have traveled for days to present us with their requests. Others have been turned down by everyone else they’ve asked. And often we’re forced to say no, toolike I’m going to have to do with these ladies right here.”

Standing before the women, he turns to Sarfraz. “Your budget for the Wakhan is finished for this year, no?” he asks. This is true, but it’s also a piece of pre-scripted theater that will lay the groundwork for a diplomatic denial of the women’s request.

“Finished,” Sarfraz confirms while pulling out his phone, which is ringing. He glances at the number and passes it to Mortenson, handling it as if it had spontaneously caught fire. It’s Tara Bishop, calling from Bozeman.

“Oh, hi, sweetie!” Mortenson says. He listens a moment. “Well, right now I’ve got some women who want a vocational center. I’ve got like 20 of them surrounding me, and they’ve got this really feisty leader, but I’m afraid we’re gonna have to say no, because Oh. All right, I promise. Yes, sweetie. Bye now.”

His next words, directed at the women, are translated by Sarfraz: “Wife-Boss says we must somehow find the funds for your vocational center. Wife-Boss also says that you should consider using your vocational center to start a book club”

Sarfraz’s translation is cut short by yet another phone call. This time it’s Suleman Minhas, the CAI’s operations manager for Pakistan, ringing from Rawalpindi to work out details of an “emergency” that arose earlier that day.

The man with no underwear, it seems, has been summoned to have a cup of tea on Sunday afternoon with General Pervez Musharraf, the president of Pakistan.

We have 72 hours to get to Islamabad.

EARLY THE NEXT MORNING, the group splits up. Sarfraz will spend the next week pushing east, all the way to the end of the Wakhan, where the most remote school in the CAI archipelago is located. Meanwhile, Mortenson climbs into one of Khan’s pickups. We spend the next three days barnstorming down the same roads we’ve just come up, while Mortenson works the phone to set up a series of charter flights. As Wellington once said of Waterloo, what happens after that is a close-run thing.

In Faizabad, we almost miss our plane but manage to board at the last second. In Kabul, Wakil Karimi nearly loses our luggage but performs a miraculous baggage transfer through the front door of the airport. Later, as our flight makes its approach into Islamabad, the pilot announces that a looming storm may force us to return to Kabulbut Mortenson’s connections in the Pakistan military arrange for a VIP clearance that allows us to land. We touch down just a few hours after Al Jazeera reports that the Pakistani parliament has initiated impeachment proceedings, pitching President Musharraf into the worst political crisis of his life.

The following morning, a small black Toyota Camry pulls up to the security barrier at the Marriott Hotel, where, five weeks from now, a truck bomb will demolish the entire building and kill 60 people. Musharraf’s office makes it clear I’m not welcome, so I cool my heels while Mortenson, clad in a spotless white shalwar kameez and a black vest, gets in the car. In addition to Suleman, he is joined by two other members of the Dirty Dozen: Mohammed Nazir, 29, who manages several projects in Baltistan; and Apo Abdul Razak, 75, who spent 40 years cooking for mountaineering expeditions in the Karakoram and now serves as Mortenson’s diplomatic emissary to recalcitrant mullahs, greedy bureaucrats, and bad-tempered gunmen.

Mortenson and the crew are shuttled into the military section of Rawalpindi, where the president lives, and deposited in front of an elegant, mogul-style residence. Bilal Musharrafthe president’s soncomes out to greet them. They are ushered into a waiting room adorned with a red carpet.

“Simple but elegant,” Mortenson later says. “Bilal presents a tray laden with almonds, walnuts, candy, and yogurt-covered raisins. Then a butler comes in and asks if we want teagreen tea with cardamom and mint. And then, all of a sudden, President Musharraf himself walks in. He sits down right next to me and says, ‘Thank you for taking the time to come and see us. We have prepared a brunch, and hopefully you can stay for a while. Perhaps we may even have time for three cups of tea today.’ “

Musharraf seems especially interested in acquainting himself with the CAI’s Pakistani staff, and Mortenson is happy to sit back and let them talk. Eventually, everyone is urged to move into a dining room where they’re joined by Musharraf’s wife, Sehba, and sit down before an elaborate buffet featuring chicken, mutton, and a host of other traditional dishes.

“We were supposed to meet him for 30 minutes,” Mortenson will tell me later that night, back at the Marriott. “We ended up being there for nearly four hours.”

This provokes astonishment and wonder from the CAI staff. “Most high-level delegationsthey only get very short meetings with Musharraf,” marvels Nazir.

“No one will ever believe that humble villagers like us were there for almost four hours. Our families will never believe it. They will all think us mad.”

ALAS, THE MEETING’S IMPACT will be negated in three days, when Musharraf resigns from office. But as Mortenson sits and listens to his staff that afternoon, he isn’t thinking so much about the future. Instead, he’s reflecting on something that took place 37 years ago.

“When it came time for my dad to open the hospital in Africa back in 1971,” he tells me later, “he got up and gave a speech in which he predicted that, within ten years, the heads of all the departments would be locals from Tanzania. ‘It’s your country, it’s your hospital,’ he saidand when he did, there was this collective gasp from the expat audience. This was a community, you see, who assumed that getting anything done required a mzungua white manwielding a kiboko, a hippo-hide whip.

“But you know what? That’s exactly what happened. My dad died of cancer in 1980, and two years later, when we got the annual report from the hospital for 1981, my mom showed it to me with tears in her eyes. Every single department head was from Tanzania, just as he’d predicted.”

I ask Mortenson if he has any similar predictions to make.

“My hope,” he says, “is that, in 15 years, the Dirty Dozen will all be women.”