A place one can never return to grows in the mind. In mine, wind scours a scree field; a long-haired man peers down between the crenellations of a mud watchtower; a woman dozes on a wooden bed in an enclosed courtyard. The steep V of a mountain pass marks a half-remembered, half-imagined map. This is the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, where there are few roads and many bandits known as badmash. Much of the land is tribal, and the laws of the nations to the west and east don’t apply. Between 2001 and 2004, I reported from the area with too much familiarity. Even though it was stunningly risky and illegal, I kept emerging unscathed, so I grew cocky. I thought I knew the place, because I found solace in its forlorn landscape and cherished the dark humor of the people I met. I believed I belonged. This was my first mistake.

IDP

Char-i-Qambar Camp, Kabul

Char-i-Qambar Camp, KabulLittle

The IDP’s fled their homes in Helmand Province to escape the unrest and fighting between NATO forces and the Taliban.

The IDP’s fled their homes in Helmand Province to escape the unrest and fighting between NATO forces and the Taliban. Basbibi’s grandson.

Basbibi’s grandson.One-armed

Jangora, North West Frontier Province

Jangora, North West Frontier ProvinceI arrived on October 7, 2001, . F-16’s roared westward overhead to launch air strikes against the Taliban. The tribesmen could hear but not see the fighter jets, so they fired their rifles into the sky. On my second visit, when an American photographer and I were staying in the tribal areas with a family we’d befriended, members of the local Taliban came and demanded, “Give us the Christians.” My hosts refused. We spent a sleepless night listening for fighters climbing the high earthen walls surrounding the home, then left at dawn. On my third visit, I traveled to South Waziristan, on the Pakistan side of the border, during a lull in fighting against a powerful mujahideen leader named Nek Mohammad, who was . I lay in the backseat of a taxi, pretending to be the sick wife of one of Mohammad’s fighters. In 2004, I traveled for several days with a friend and seasoned Afghan Newsweek reporter, , to meet a well-known Pakistani journalist named . As we drove the border’s steep mountain roads, Khan gave me his wife’s burka and flip-flops and put his two-year-old daughter on my lap so we would blend in. Khan was later assassinated for his investigative reporting, and his wife has since died in a mysterious bomb blast.

On that trip, I saw monkeys in pine trees. I saw women gathering wood who claimed to never have seen a car before. I saw the side of a mountain strewn with white rocks. Until several months earlier, they’d spelled out LONG LIVE MULLAH OMAR—. At the trip’s end, at the very moment I thought I’d made it to the relative safety of Bannu, we were detained by Pakistan’s military intelligence, blindfolded, cuffed, and bundled into the back of a car. The windows were papered over. There was a gun to my head. I was let go on an airstrip in the middle of nowhere pretty quickly, but Yousafzai was detained in prison for six weeks to serve as an example: You don’t travel with an American.

Until that point I saw myself as different, special, destined to work on this border. The contacts I had and the fact that I was a woman convinced me that I could navigate a landscape others couldn’t. I’d made my peace with risk, but until that point I hadn’t realized that I wouldn’t be the one to pay for my mistakes. The imprisonment of my friend changed that.

[quote]“Zama mashoom halek day,” I said—“I am having a boy.” The women all clapped and murmured. My host pulled her dress up around her breasts so that her bare stomach was exposed. “I’m not pregnant,” she cackled. “I’m sick!” She stopped laughing.[/quote]

After Yousafzai was released, I accepted that I could never return. If I did, I’d further jeopardize others—translators, drivers, friends. It was a painful decision made more so over time. At first, I didn’t realize how deeply the place had impacted me. It wasn’t about missing the rush; I didn’t long for the metallic taste of cortisol in the mouth, the aftermath of an adrenaline jag from one dangerous drive or another. I missed the stories. And the best came from women. I’d spent most of my time in villages lazing around on wooden beds called charpais, listening to people talk. The men discussed who had a new weapon, the going price for a cartridge. The women told remarkable stories—of the village’s blood feud, the heroin addict who’d come in search of safe haven. Men here may eat first, but women hold the power of story.

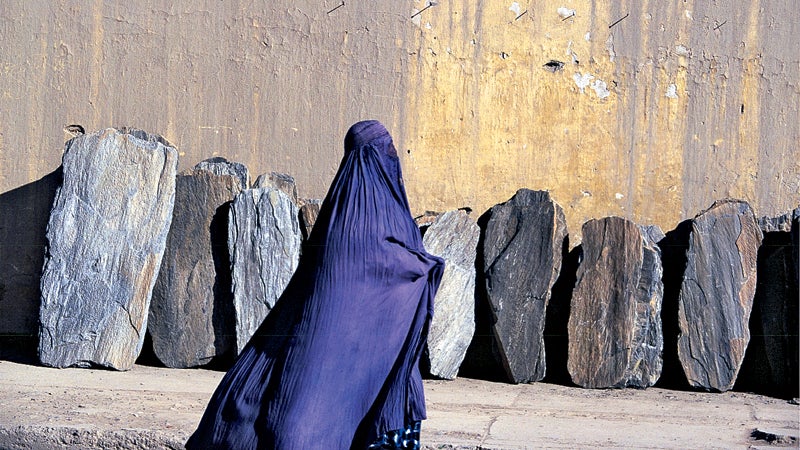

Women make up roughly half of the 42 million Pashtun people in the borderland. The kind of hardship they know is rare. Some are bought and sold, others killed for perceived slights against family honor. But this doesn’t render them passive. Most of the Pashtun women I know possess a rebellious and caustic humor beneath their cerulean burkas, which have become symbols of submission. This finds expression in an ancient form of folk poetry called landay. Two lines and 22 syllables long, they can be rather startling to the uninitiated. War, drones, sex, a husband’s manhood—these poems are short and dangerous, like the poisonous snake for which they’re named.

To ask a woman to sing a landay is to ask what has happened to her. If she agrees, in those two lines she’ll sing you the story of her life and of the places she comes from—places that, for me as for most of us, are impossible to go to. The lure of such danger may no longer drive me as it once did, but the fascination with borders, with traveling to the edge of a place, still has a pull. Before Thanksgiving 2012, I decided to return to the Afghan side of the border to collect landays. It was safer than the other side and as close as I’m likely ever to get to the region that haunts me like no other.

Along with , a photographer who has worked in Afghanistan for more than 20 years, I’d begin in Kabul, then venture as close to the remote Pashtun villages as it was reasonable to go. We’d give ourselves a month to gather enough landays to . Seamus and I met more than a decade ago, when he saved me a seat on a bus bound for northern Iraq at the beginning of the war. We’ve been close friends ever since. He’s an excellent guy to have on your side—kind, funny, virtually indestructible. We’ve kept a fierce pace while working together in Somalia, Nigeria, and Afghanistan, but this trip was different.

At four months pregnant, I was moving slower than usual. I threw up some mornings. It felt like an ant colony occupied my calves. Due to the exigencies of morning sickness, I was living on crackers, which are in short supply in Afghanistan. So I hauled several pounds of energy bars along with gifts: lipstick, scarves, and books of my own poems. (These proved unpopular.) In Kabul we met our translator, whom I’ll call Z. A tenacious young woman who has been her family’s breadwinner since her father died when she was a child, Z. belongs to a new generation of urbane Afghan women who’ve flourished with the influx of foreigners since 2001.

She met us in the Afghan home where we stayed with two friends: an American named Jean Kissell, who lives and works between Afghanistan, the Emirates, and Vermont, and her colleague, Mohammad Nasib. When the Taliban fell, Nasib, an Afghan-American who’d been living in Washington, D.C., and working with the United Nations, decided to do something about the rampant problem of drug addiction in Afghanistan. With the help of Kissell, he founded the , which, among other things, operates rehabilitation centers for addicts. WADAN’s ties to rural people run deep, so Nasib and Kissell know how to do unusual work, like collecting poetry in hard-to-reach places.

Refugee camps in Kabul seemed the right place to begin. There, farmers who’d recently fled tribal villages were trying to eke out an existence until it was safe to go home. We started at Charahi Qambar, a camp of 6,000 on the outskirts of Kabul. The previous winter, nearly two dozen people had frozen to death there. Traffic was worse than ever as we approached the camp. Toyota Corollas jockeyed for inches at roundabouts and waited for hours as convoys of U.S. military vehicles crawled east toward the Pakistani border, beginning the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The road to the camp was lined with boys hawking pomegranates. The fruit was rock hard, its flesh brown and green. Behind the market stalls, a tent city rose abruptly. We pulled in front of two tents that served as a clinic and a school. With WADAN’s help, we’d set up a meeting with the camp’s elders—there’s no way to talk with a group of Afghan women at home without speaking first to their husbands. Our hosts, a cluster of about a dozen men, did not look welcoming. Some appeared incredulous, others bored or stoned. They eyed us sharply, and one ushered us into the circle of broken chairs that served as their conference room. It can be rude to wander into a refugee camp. People are often forced to live private lives in public due to lack of space and shelter, so the illusion of modesty and propriety is important. Hoping for the best, we introduced ourselves and asked how the camp was faring.

“Nothing has changed since last year,” said one elder. Glassy eyes shone from a gray face. Since the tragedy of the previous winter, when the refugees had frozen, there’d been a spate of disappointing press visits. “People come to visit and do nothing,” the man said. “We’re still cold and we’re starving.” The aid program at camp seemed to work like this: Kids who went to school received bags of rice and wheat to take home. If the kids didn’t show up at school, the family didn’t eat. After a few minutes of general discussion, I asked about the poems we’d come in search of. I hoped the men might find it refreshing that we were interested in culture rather than the familiar woes.

[quote]To ask a woman to sing a landay is to ask what has happened to her.[/quote]

“We don’t know anything about poems,” the man snapped. “We’re uneducated people.” Many of the men began to wander away. But one, sturdy and middle-aged, with a smile in his eyes, pulled me aside. He led me into a warren of tarps and earthen alleyways. Heaps of garbage and human waste were piled among the narrow paths. I hopped over puddles of gray sewage in a pair of old sneakers while Z. proved perfectly nimble in high heels. Without saying anything, the elder deposited us in front of a blanket stitched with dust that served as the door to his home. Inside the makeshift shelter, his wife was dressing to go to a neighbor’s wedding. She was tall, with strong white teeth and gold wire earrings.

“I’m pregnant, too!” she cried, looking at me. She grabbed my puffy gray coat, then rubbed her hands over her protruding belly. Two twentysomething women in heavy velvet dresses appeared from two different blanketed doorways: her daughters-in-law. Then a half-dozen other women appeared out of nowhere.

“Zama mashoom halek day,” I said—“I am having a boy.” The women all clapped and murmured. My host pulled her dress up around her breasts so that her bare stomach was exposed. “I’m not pregnant,” she cackled. “I’m sick!” She stopped laughing. Her abdomen was swollen with a mysterious ailment. “Can you tell me what is wrong with me?” she asked.

She barked at a daughter-in-law, who disappeared behind a woolen blanket and reemerged with a white box of pills, which she handed to me. This was the medicine the clinic at the camp had given her: birth control. “What is this?” my host asked. “How do I take it?”

The directions were in English, so I read them aloud as Z. translated. “It’s birth control, “ I said. “This will keep you from having a baby.”

“I’m too old anyway,” she shrugged. “And something is wrong with me.” Still, she was grateful for my help and invited me along to the afternoon’s wedding. She grabbed my arm and pushed me under the blanket and back into the neighborhood’s alleyways. Soon we came to a compound made of dribbled mud: the bride’s home. Inside, the air was warm and heady with sun, sweat, hay, and the press of dozens of bodies. Weddings are segregated by sex, so there were no men. The women were chanting—growling, almost. One, with gold front teeth, was beating a hand drum. The dirge sounded more funereal than celebratory. I understood one word—Sangin—the name of an opium hub in the restive province of Helmand, from which these women had fled some months earlier. Z. translated for me: They were singing of war. One morning before dawn, as a NATO bombing raid raked fire over their village, these women had gathered up their children and fled. An old woman with a white braid said that a helicopter gunship had mistaken a dozen farmers for fighters and shot them all. Her husband was among them. Shrapnel had shredded her three-year-old grandson’s eye. Others, I was told, drowned when the swarm of terrified people surged onto a bridge too narrow to hold them all.

To the drum, they sang:

What should I do, oh God?

My homeland of Sangin is besieged by NATO helicopters.

It wasn’t easy to pry landays out of the women. After the wedding in Charahi Qambar, I tried to meet with the lead wedding singer, the woman with the gold teeth.

“This is impossible,” my host, the woman with the swollen belly, told me. “She must come from another camp, and she can only travel for weddings. If you go there and her husband finds out that she sang for you, he will kill her.”

She proposed an alternative. “There’s an older singer, a widow named Basbibi,” she told me. Perhaps, if I returned to the camp another time, Basbibi would sing. A few days later I returned. Once I was seated in my host’s home, she opened my bag and took my iPhone. She thought it was a voice recorder. I wasn’t to record any of the women, she said. I turned off the phone. Basbibi entered and tugged the burka from her head. She wore a white braid down her back and placed her three-year-old grandson on her lap. He had one scarred eye. She tried to give a fake name at first, but I recognized her from the wedding as the older of the two singers, whose husband had been killed by the NATO forces.

“There are too many sorrows to sing of,” she said. She’d lost her husband; her grandson was half-blind. Life in the camp was no better. Her brother had recently been arrested for killing another man in a fight over water. He’d been taken away to the infamous Pul-e-Charkhi prison, . She crouched and sang,

In Pul-e-Charkhi, I’ve nothing of my own

Except my heart’s heart lives within its walls of stone.

Each night I counted the poems I’d collected as if hoarding treasure. It was slow-going. Usually, when reporting, there is a midway moment when I realize I’ve got the story. That moment wasn’t arriving. There was something about the bubble of the capital that made us feel disconnected. Then there’s the fact that eight out of ten Afghan women don’t live in cities. We weren’t getting close enough to the mountains where these poems were born. We had to travel nearer to the border. But my calculus was different now. The choices I made had bearing on the person temporarily making his home inside me.

Seamus had already given our unseen friend a name: Puddin’ Jelly, after a poorly translated menu item at our favorite restaurant in Kabul. When we were sleeping on floors, he wordlessly handed over his mattress so that Puddin’ would have extra padding. He always gave me the last Snickers. After a bumpy ride, he’d turn to me and ask, “How’s Puddin’?”

His thoughtfulness reassured me, and we decided to head east to Jalalabad, the capital of Nangarhar province. One of the country’s largest cities, Jalalabad . Before Islam arrived, it was a sacred Buddhist region. The road from Kabul east to Jalalabad is less than 100 miles of switchbacks and tunnels blasted out of the rock by the Russians. Now the road was undergoing urgent construction to facilitate the Western pullout from Afghanistan. Winter was a bad time to drive it. This wasn’t simply a matter of militant roadblocks. It was a question of car accidents. Seamus and I decided to fly and bought empty seats on a flight that the Japanese government had chartered for its aid workers.

[quote]I felt no surge of relief, no sense of accomplishment. There was nothing finished about these poems, and I’d soon leave the women who sang them behind.[/quote]

This, too, comes with risk. Many flights to Jalalabad are greeted by Taliban gunfire. Our pilot dove steep and straight toward the airport, a military base, in order to avoid the threat of bullets. As we taxied, I spied two American soldiers in shorts going for a jog. Behind them, in a hangar, were two diminutive snub-nosed aircraft with propellers: space-age versions of remote-control planes kids built from kits. It took a moment before I realized they were drones.

In town we slept on the floor of an office owned by friends of Kissell and Nasib. (The hotels in Jalalabad are expensive and loaded with Taliban spies.) To keep a low profile, our hosts requested that I wear a burka outside at all times. I loathed the constriction, but there was a perk to stifling beneath that blue fabric: it earned me the right to study the market crowded with tailors and peddlers, the outdoor pool hall with snooker tables tucked under a tarp meant for refugees.

On our third day, we discovered a trove of landays in the person of Sharifa Ahmadzai, a fiftyish businesswoman who owns rug factories throughout the country, whom we met through a local professor. She couldn’t travel to her home village anymore, because the Taliban wanted her dead. For people who represent the modern world, it’s no longer safe to go home to villages now dominated by militants. Still, Ahmadzai loved the ancient poems. She recited one she’d heard by phone from a kinswoman in her village, the mother of a Taliban fighter named Nabi who’d recently been killed by a drone strike:

My Nabi was shot down by a drone

May God destroy your sons, America, you murdered my own.

We didn’t go into the borderlands, but we managed to reach them another way: a local women’s affairs office arranged for seven teachers from faraway villages to collect landays from girls. At week’s end, we hosted a small lunch for the teachers, paying bus fare for them and a family escort. They filed into the office with scraps of paper scrawled with landays they’d gathered from teenage schoolgirls. Listening to them and carefully recording the treasures they’d brought was a bit like a game of telephone. I taped them one by one, hoping I was getting the words right.

The next day, it was time to return to Kabul, so we tried to finagle cheap seats on a charter plane. There wasn’t one. We had to go by road. The night before we left, Seamus stayed up late watching a pirated copy of on his laptop. Through the office wall, I could hear Carrie’s hysterics. The next morning, around 5 A.M., the sound of a blast woke us. “Shit!” I uttered, sitting up fast and clutching my swollen belly. “B����������������!” Z. said at the same time. About three miles away, a suicide bomber had blown himself up. Seconds after, another. The bombers .

A few hours later, Seamus, Z., and I climbed into an SUV owned by our host to run the winding gauntlet from Jalalabad to Kabul. Our driver was a mustached man in a leather coat who spoke no English. There was only one working seat belt, and I grabbed for it. “Sorry, I need the seat belt,” I said. Z. glowered beside me. She didn’t much care about the belt, but she had to sit in the middle, which was neither comfortable nor culturally appropriate, since she had to squeeze in leg to leg next to Seamus. I pretended not to notice. On both sides of the road, the jagged river valley rose over sheer rock faces. The walls looked too steep to harbor armed militants, but they did. The black mouths of the tunnels that the Soviets blasted in the eighties gaped at us. Entering them has always stopped my breath. This time my jaw was clenched too tightly for nausea. After a few minutes we emerged from the tunnels, and the landscape cut into sharp valleys that we drove through at top speed. Our driver exhaled deeply and picked up his phone to call our host once again and report that we had made it beyond the hairiest part of the drive. I pulled Diet Cokes from the plastic bag at my feet and handed them to Z. and Seamus.

I felt no surge of relief, no sense of accomplishment. There was nothing finished about these poems, and I’d soon leave the women who sang them behind. When the military convoys rolled out of Afghanistan on roads the Russians had built, what would happen to brash young women like Z.? The only world she knew was one where she was free to do as she pleased. When the international community was no longer paying attention, what jealous member of her family might rise up against her, claiming religion as his cause?

I thought of this landay, which one of the schoolteachers brought us:

When sisters sit together, they’re always praising their brothers

When brothers sit together, they’re selling their sisters to others.

I wondered, too, what the next year would yield in my life—whether I’d have the courage and capacity to return, or if, by necessity, I would leave this place behind.

Eliza Griswold’s is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.