Over the weekend, the number of people in the world who know precisely where Forrest Fenn hid his treasure��supposedly doubled. We know the finder was a man, from “back east,” according to Fenn, and that he wishes to remain anonymous.��

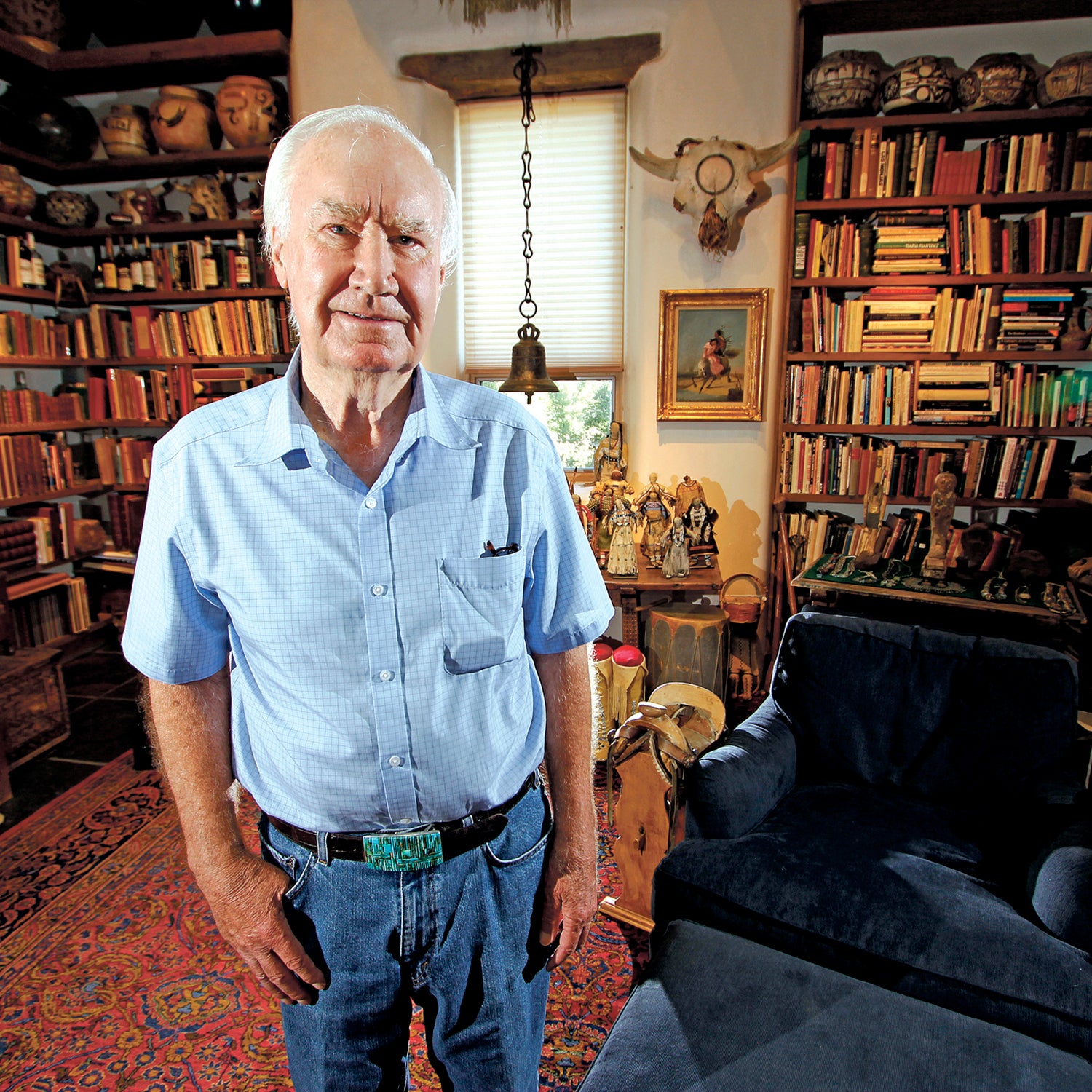

Fenn, of course,��is the former art-and-antiquities dealer who in 2010 hid a box of treasure somewhere in the Rocky Mountains and wrote a poem with nine clues leading to its hiding place. The finder, on the other hand, is anyone’s guess.

So until we know more about where it was, who found it, and what he plans to do now, the hunt is in a maddening kind of limbo: it is both over and not, the chest is simultaneously newly found and perhaps also gone forever. Call it Schrödinger’s Treasure.

���Բ�’s ��included a promise of more information and photos in the days to come, but Dal Neitzel, who runs the website Fenn used to post the message, says Fenn has now backed away from that statement, saying the treasure’s location is “personal and confidential.” Some are anxiously waiting for more information. are basically coughing “bullshit” into their hands, saying the whole thing is a scam and the contents of his chest are ill-gotten gains.

Absent proof that the treasure was ever out there, it doesn’t take a ton of natural skepticism to feel very suspicious about what’s been going on.��And if that’s your disposition, this “anonymous finder” business reads like a convenient way to call off the hunt without having to admit that it never existed in the first place. After all, five people have died in pursuit, and hunters have started filing lawsuits claiming Fenn misled them.

But when it comes to finding valuables, anonymity isn’t all that suspicious. There’s a culture of discretion in the treasure community. Longtime hunter W.C. Jameson wrote in his memoir, : “Announcing a discovery often leads to negative and unwanted developments, primarily the loss of any treasure that may have been found.” In other words, finders are not keepers if they make a big fuss about it.

In this case, the problem with telling everyone about the location of ���Բ�’s treasure is that there’s a good chance it doesn’t legally belong to the person who found it. It varies by state, but in general, treasure found on private property belongs to the land owner, not the finder. Pretty much the only way to stay out of court is to negotiate the split of any findings ahead of time.��

On federal land, like national parks and national forests, treasure hunters need permits to keep anything they find, and even then you’re going to need lawyers, because ���Բ�’s treasure doesn’t fit into any category for which the federal government has a neat and tidy legal definition. It wasn’t “lost,” “misplaced” or “abandoned.” At ten years old, it’s not really from antiquity. It may not even fit the legal definition of a treasure.

“The question here is whether it’s even a treasure trove,” said Ben Costello, an attorney and board member of the 1715 Fleet Society, which researches and documents the recovery of shipwrecks. “I don’t think it is, because the owner is known.”

Property where the owner is known is supposed to go back to that original owner. We don’t have laws for gold and jewels that the owner doesn’t want back. It’s just not a situation that comes up.

But maybe Fenn thought of all this ahead of time? He won’t say.

“I would have to make the assumption that it could be legally claimed by someone,” said David McCarthy, a numismatist��who handled the discovery and sale of a $10 million dollar treasure called the Saddle Ridge Hoard, in 2013. “There are public lands where citizens of the United States can keep what they find.”

Assuming someone does have a legal claim to their find, the second hurdle is the tax situation, and it is daunting.

“I saw the announcement that someone found ���Բ�’s million-dollar treasure and I thought ‘Do they know they’re about to pay $450,000 or so in income taxes?” says Larry Brant, a tax attorney in Portland, Oregon.

No one is sure just how much the contents of ���Բ�’s chest is worth, but Brant says the IRS views treasure just like any other income. The moment you find it, you owe taxes on it for that year, regardless of whether you auction it off, give it to someone, or keep it in your living room as a conversation piece.��

Then there’s the matter of state and local taxes. Just like the winner of a state lottery who has to pay taxes in that state, or an NBA player who has to file income taxes everywhere they play, treasure finders have to pay taxes wherever they find treasure. So if it was in New Mexico, that’s an extra 4.9 percent��off the top. Wyoming, however, takes nothing. Location matters.��

So, let’s say the treasure is worth a million dollars, which is what Fenn originally said it might be worth. The finder owes about half of it in taxes, and let’s say half of what’s left goes to the lawyers he’ll need to sort out his claim to the property. Then there’s the Chicago woman who against both Fenn and the anonymous finder claiming he’d stolen her solve. It all adds up to an income-to-headache ratio that doesn’t look so good.��

Which brings us to the most interesting, and hopeful, reason for the finder to stay anonymous and obscure the location of the find. It came from��Neitzel, who has been running devoted to the Fenn Treasure for over nine years. His initial reaction was denial when he got the message announcing the find—he thought someone was spoofing ���Բ�’s email. But now he says he’s come to terms with it.��

“My main concern is that Forrest puts closure on this,” he said. “People need to know if they were close.”

He says over the years, one of the ideas that people on his blog keep circling back to is the idea that if they found ���Բ�’s treasure, they would take a little something out for themselves, keep it quiet, then put it back where they found it, without ever disclosing the location. It’s an option that would save everyone a bunch of taxes, legal fees, and hassle. Wouldn’t it be great, Neitzel said, if the hunt were over, but the game could go on?