The Obsessive Quest of High Pointers

Some of the world's most passionate athletes are high pointers, climbers who will do anything to reach the tallest point in every state, county, or whatever other designation they can dream up. A lot of those peaks aren't so tall—like Delaware's 447.85-foot Ebright Azimuth—but there's plenty of challenge in this quest. Just ask John Mitchler, who had knocked off everything on his dream list except the tallest spot in a remote U.S. territory: Agrihan.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The climb was scheduled to begin at dawn, but at dawn there was nothing to climb, just a tiny hump of land on the horizon. We were still miles away, chugging along on the northwestern Pacific Ocean. Over the next few hours the hump grew larger, transforming into the cone of a volcano. From the boat I could see cliffs, a lava-rock seashore, and dense jungle rising to grassy ridgelines that crept upward like veins to a heart. Dark clouds obscured the summit. It looked like a place that could swallow you whole.

Our group consists of 11 American climbers, one Brit, and six porters from the nearest population center, Saipan, 248 miles to the south. Saipan is part of a little-known U.S. territory called the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands, and the top of the volcanic island we’re approaching—called Agrihan—happens to be the territory’s highest point. At just over 3,000 feet, it’s nothing special as mountains go. But as far as anyone knows, it has never been climbed. Fifteen years ago our expedition leader, John Mitchler, decided that he wanted to be the first. Since then, no one has been able to talk him out of it.

At 9:04 a.m., the crew of our 60-foot boat, the Super Emerald, dropped anchor and winched a small skiff over the deck. Loading it up, they implored us to not fall overboard because “the sharks here are not friendly.”

We filled the skiff with duffel bags of climbing gear and gallon after gallon of water. We brought a ton of it—250 gallons in all, weighing precisely 2,082.5 pounds. Roughly a gallon per person per day for the nearly two weeks we’d be here. It would take five trips from boat to shore to off-load all of it, and then the Super Emerald would turn back for Saipan. Over the next week, we would haul those jugs up to each of four camps en route to the top, returning to the beach every night to fetch more.

Looking toward the shore, I could see John and the crew tossing jugs toward the sand like a fire brigade. Then, in a blink, they were done, and John disappeared into the jungle, heading uphill, already sniffing out a route to the top.

To complete a first ascent is to be written into history, but unclimbed mountains are a dwindling resource. The Alps were once so formidable that, as recently as 1723, a respected scientist published an account of the various species of dragon to be found there. Dragons proved absent, however, and alpinists decided they liked climbing anyway, and began tagging summits all over the world. They checked them off at a furious pace, and climbing firsts are mostly now about new routes or new styles or some other minute or oddball differentiation—youngest, oldest, fastest, first without oxygen, first cancer survivor, first blind person, .

High pointers don’t limit themselves to mountains. They’ll go to the top of anything so long as it isn’t man-made. You might say that there’s no climb too small. Many joke about their single-minded focus on summits, calling it “the sickness.”

John is trying to carve out his own little niche in that world, but he’s doing it by chasing quantity, not quality. Some climbers pejoratively call this peak bagging—summiting mountains just to say that you summited them, regardless of how difficult they are. Defenders claim that the beauty isn’t in pioneering a new route but in the completion of a list—like the Seven Summits, the highest point on each continent.

John belongs to an even more curious subset of peak baggers called high pointers. High pointers don’t limit themselves to mountains. They’ll go to the top of anything so long as it isn’t man-made. You might say that there’s no climb too small. Mighty Denali in Alaska or modest are equal checkboxes on the list. High pointers tend to be engineers, scientists, programmers—fans of empirical data with a passion for details. Many joke about their single-minded focus on summits, calling it “the sickness.” When they say that about John, they aren’t really joking.

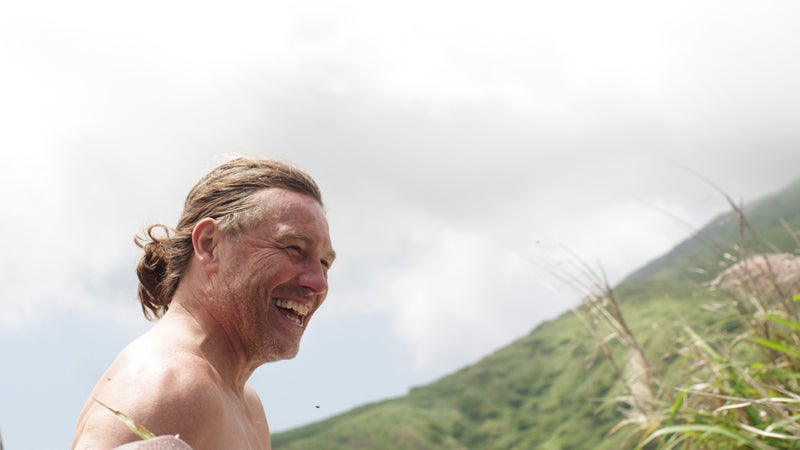

John lives in Golden, Colorado. He’s 62 but looks younger, with a square jaw and long hair always pulled back into the kind of man bun that tends to belie his conservative politics. A geologist by training, he now spends most of his time running several small businesses—a marketing firm, an adventure travel agency, and a spice company called JAK Seasoning among them—that he owns with his wife, Kathy.

In the 1980s, John began spending much of his spare time and money reaching the highest point in all 50 U.S. states—which, he says, “most high pointers agree is the coolest list.” Some of those summits, like Alaska’s 20,310-foot Denali, are truly arduous, dangerous climbs. Others, such as Delaware’s 447.85-foot Ebright Azimuth, are mere hills.

By John’s reckoning, more people have climbed the Seven Summits (416) than the 50 high points (305). When he finished in 2003, he marked the occasion by setting another goal: he’d climb the high points in all five inhabited U.S. territories, which no one had ever done. “I do love checking off a list,” he says.

He got to it. Guam and Puerto Rico were practically drive-ups. The U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa: no problem. By the summer of 2014, all that was left was Agrihan.

Perhaps Agrihan has never been climbed because it’s so remote, or because there’s no reliable source of fresh water, or because it’s brutally hot and humid. Most likely it just never occurred to anyone that it would be worth doing.

“For most climbers, it’s either Everest or bouldering or Alex Honnold and all that,” John says. “This is really bizarre climbing.” That was basically his sales pitch the first time we spoke on the phone. I’m not a high pointer. I don’t even like climbing all that much. When the mountains are calling, I generally pretend I have bad service and __n’t hear wh__ they’re say__. In 2016, I climbed to 20,000 feet in Bolivia, but I was searching for the remnants of a plane crash, and I didn’t bother to summit. Since then, my standard line has been that if I’m going to climb a mountain, there had better be a plane crash up there.

Agrihan, I was told, would be different. We’d be on a tropical island, not a frigid mountain, and we wouldn’t be covering much ground. Our route would be just three miles long, with 3,000 feet of vertical gain. There wouldn’t be any altitude issues, and the route wouldn’t be technical, just a muddy stretch near the top where we might place ropes. The hard part would be the glacially slow process of building trails through heavy jungle and aptly named sword grass. We’d establish base camp on the beach and a series of four higher camps for stashing water and supplies en route to the summit. At first we’d shuttle two or three gallons at a time to camps one and two. Then, as the porters set up the higher camps, we’d haul roughly half of that to camps three and four. If we could get a couple dozen gallons to camp four—about two gallons per person—that would be enough for everyone to summit. It would be hot, wet, and extremely slow going, with lots of grunt work and little fanfare if we succeeded. But in 1953, a plane had gone down somewhere in the crater. So I guess I was in.

Our base camp is a semi-abandoned six-room building left over from when Agrihan was used as a coconut plantation and is currently losing a decades-long endurance contest with the heat and humidity. Ever since the Spanish came ashore in 1565, the island has been intermittently inhabited and abandoned, following the whims of whichever superpower controlled it—Spain, Germany, Japan, and currently the U.S. Last abandoned in 2010, its population when we arrive is exactly two: Eddie Saures and Jeremy Topulei, who grew up in Saipan and came to Agrihan last year to prepare the island for resettlement. They spend their days fixing up the place and taming the jungle around the scattered buildings. Survival depends on their vegetable garden, collecting rainwater, jungle fruit, the fish they catch, and the pigs they hunt, along with 50-pound bags of rice and a 30-pack of Bud Light delivered quarterly.

Perhaps Agrihan has never been climbed because it’s so remote, or because there’s no reliable source of fresh water, or because it’s brutally hot and humid. Most likely it just never occurred to anyone that it would be worth doing.

I spend the first full day shadowing John as he picks his way up toward the mountain. By nightfall our trail is still a modest thing. Snaking through the shaded jungle for an easy 20 minutes, curving around felled palm trees and startled lizards, it rises only slightly before leaving the shade and hitting eight-foot-tall sword grass. From this point on, our machete-wielding porters whack a shoulder-wide path straight up the fall line toward the ridgetop. The sword grass is thick and nasty stuff, like a cross between bamboo and corn. Its serrated blades slice any exposed skin; when cut to ankle height, the stalks stand straight up like punji sticks. In the grass, there’s no protection from the sun, and the air is 87 degrees with 80 percent humidity. The sheer thickness of the growth stifles airflow, and hiking up the ridge is like breathing into a paper bag inside a sauna.

It’s not just the heat and the foliage; there are also flies everywhere. Millions of them swarm our eyes, noses, mouths. At one point a fly lodges itself in my left ear, seemingly stuck until, 40 minutes later, I finally hook it with my finger and it breaks in half. Then the other flies seem to sense his demise and redouble their efforts to get in my ear and harvest the smooshed bits of their comrade.

The first two times John tried to climb Agrihan, he wore a head net and covered up to try and combat the insects. Now he just lets them swarm.

That’s right. My apologies. I haven’t mentioned the first two climbs.

In 2014, John chartered the Super Emerald for four days with a high pointer named Roger Kaul and his nephew, Clint, who is on this trip, too. That group, along with three porters, braved the heat, humidity, and flies as long as they could but made it only halfway up the mountain before the boat had to return to Saipan. “That was pathetic,” John says. “Just embarrassing.”

In 2015, they doubled the size of the expedition: six climbers, five porters, and a documentarian. They hacked their way to within 26 vertical feet of the top and identified what they thought was the summit—a vertical column on the volcano’s rim. But they were separated from it by a deep mud valley that was too dangerous to traverse without climbing gear, which they hadn’t brought. So they turned back.

This is where the shape of John’s obsession really becomes clear. Because whatever wilderness experience or trial-by-flies John wanted to have on this island, he’s had it. Twice. But he hasn’t touched the summit, so he’s back. There’s a tinge of desperation in his efforts. John’s not so much an explorer or a pioneer as an eccentric collector lusting after the final piece of a set. That’s no metaphor. He collects almost everything. Stamps, gum wrappers, coins, beer cans, water bottles, magazines, and yes, mountains. In fact, given that he’s afraid of heights, sometimes the collecting is at odds with the mountaineering. “I don’t seek out rock climbing or ice climbing,” he says. “But if it’s there, I’ll do it.”

His real talent, he says, is data analysis. He’s very good at obsessing. To save weight, he doesn’t carry a stove or fuel and eats his food cold. He also keeps a list of the most effective cost-per-calorie energy bars. (Winner: Snickers.)

Whatever his methods, it’s hard to argue with the results. John has high-pointed not just all 50 states but 55 of the 60 national parks as well. He also wrote a county-by-county guidebook of Colorado’s high points. Though he recently stepped down from the job, for the past 20 years, he’s written and edited the glossy newsletter of the , which makes him something like the figurehead of this tribe. He knows that he could claim Agrihan if he wanted to, even without actually topping out on it. The high-pointing community doesn’t have strict criteria for what constitutes a summit—John says you should get your head above the highest point—but there’s no verification system. If you say you climbed it, you climbed it.

Like a lot of high pointers trying to summit Denali before they get too old to do all 50 states, I was climbing to prove that I was still capable of a kooky expedition in the middle of nowhere—that I was still myself.

One climber on the 2015 trip did, in fact, quietly check the mountain off his list. John did not. The fact that he hadn’t attained the true summit ate at him. He decided that he would not cut his hair until he reached the top of Agrihan. (Hence the New Age man bun.) He put Kathy in charge of chartering the boat, booking hotels, and other logistics, because you can’t effectively negotiate on price when you want something this badly.

“Don’t get me wrong, I want them to succeed,” Kathy told me before the trip. “But you can’t hear it in my voice.”

It was sir Hugh Munro, a Scotsman, who first popularized the idea of climbing a list. Back in 1873, Munro started summiting all of Scotland’s peaks over 3,000 feet—now called the Munros—and began cataloging them. In 1936, Arthur Marshall became the first to high-point all 48 (at the time) U.S. states. Vin Hoeman was the first to do all 50, in 1966. By high-pointing the U.S. territories, John is trying to join their ranks. But on the third day of our expedition, that desire to make history left him wrung out and recuperating at camp two.

Clint Kaul brought the news. A retired software engineer from Kalamazoo, Michigan, Clint returned to base camp on the beach that night and relayed that John was too tired to come back down. He had climbed the first ridge in full sun and overheated. He would stay where he was and rest.

“Can someone bring up my MP3 player tomorrow?” John asks when we reach him on the radio.

“Yeah, we’ll send it up with the masseuse,” jokes Greg Juhl, a 45-year-old ER doctor from Reno, Nevada.

Back on the beach, though, there’s some confusion as to when John tired out. He is almost always the most enthusiastic high pointer in the room. But as we prepared for this trip, he’d looked haggard and exhausted. Purchasing supplies at an Ace Hardware in Saipan, he even seemed a little irritated. “Let’s just get to the summit and get out of there,” he’d said as the group debated the merits of different gear.

Over the next two days, we continue hauling water. John stays higher up on the mountain with his MP3 player, moving gear between camps two and three and preparing to set up camp four. Many of us start the day at 4:30 A.M., hoping to carry two 40-pound backpacks full of water and supplies before the sun hits. By the morning of the fifth day, a lot of us are moving slowly and snapping at each other over little stuff. I’ve tweaked my back. Clint, who accompanied John on the other two summit attempts and helped with much of the route planning for this trip, has developed a deep cough that asserts itself each morning. “I really hate this mountain,” he says before heading uphill.

I grab two gallons from camp one and pick up a third and fourth from camp two. Once above the sword grass—just before camp three, at 1,950 feet—the flora turns to waist-high ferns. From there it’s an hour straight up to 2,520-foot camp four. When I get to camp three around lunchtime, Gary Reckelhoff is sitting there with a daypack. Thirty years old and built like a greyhound that does CrossFit, Gary always wears a heart-rate monitor and tracks how many calories he’s burning on an expedition. He’s the most physically fit member of the team, but you wouldn’t know it from the tiny load he just carried from camp two. I start to simmer with anger. And that’s before I head up to the breezier, permanently cloudy camp four, where I find John and a 51-year-old entrepreneur and nonstop talker named Tony Cobb.

During the previous two days, there was grumbling at base camp about these two. Is John still recovering? No one knows. What’s Tony doing up there?

For the past hour, I’d been rehearsing a lecture along the lines of: Are you sure you should even be here, John? But when I arrive, John comes over and tells me he’s not doing so great. He has no legs, no strength.

“I think I’m done,” he says.

Done for the day?

“Done with high pointing,” he says. “This is my last expedition.”

You can’t harangue someone who’s on the verge of giving up. John’s struggle has placed him firmly atop the moral high ground. But I’m still angry, so I move on to Tony, who is stretched out on his sleeping pad in his skivvies, a contented smile on his face. When I see this, my anger boils over. There are nine gallons of water here when there should be two dozen. I ask how he can just sit here while the rest of the group toils in the heat? Granted, Tony hauled some water on his way up, and he’s been moving gear between camps and setting up rain catchments. But it’s not raining, and the longer he and John stay high on the mountain, the more water the rest of us have to carry. My voice quavers, I’m so furious.

“Yeah, well, I’ve been needing an excuse to go back down,” Tony says when I’m done.

“I’ll give you an excuse,” I yell. “Nine fucking gallons!”

For the first time on the trip, Tony barely says a word in response. He simply gets up, packs his gear, and heads down the mountain.

I walk away to be alone for a bit. Everything feels backward. Tony is quiet. Obsessive John is quitting high pointing. I’m chewing out a team member over a climb I supposedly have no stake in. No one’s more surprised by my behavior than me.

But I think I know why I’m so invested. Nine months before Agrihan, I broke my leg in a canyoneering accident and spent 21 hours waiting for a helicopter to get me to a hospital. It was a traumatic fall that shattered both my fibula and my youth. I came out of surgery in a 32-year-old’s midlife crisis—fragile, anxious, and newly aware of my mortality.

The first time I spoke with John on the phone, he persuaded me to join the trip. But I think I needed to be on this climb more than he needed me on it. Like a lot of high pointers trying to summit Denali before they get too old to do all 50 states, I was climbing to prove that I was still capable of a kooky expedition in the middle of nowhere—that I was still myself.

So I guess John and I both need to conquer some dragons on this mountain. From camp four, it seems like the only place we’ll find them is at the mountain’s very highest point.

By day six, we’re within striking distance of the summit, except that we don’t know which summit to strike. Radar topography shows two potential high points, both situated along the rim of the crater, at 952 and 960 meters (3,123 and 3,150 feet, respectively). They’re dubbed P952 and P960. The two elevations are within the radar’s margin of error, however, so there’s no way to tell which is the true summit.

Normally, determining which point is higher would be a simple matter of setting up a spotting scope on one of them and shooting it toward the other. But the cloud cover makes this next to impossible.

“Some places have two or more high points that are exactly the same,” John says. “The purists go to both.”

Ginge Fullen is a purist. An Englishman who lives in Scotland and a former clearance diver who disarmed underwater bombs for a living, Ginge has a Mr. Clean look and is easily the most accomplished high pointer in the group, perhaps of all time. He has high-pointed 170 of the world’s 195 countries, though in 1996 he tried to summit Mount Everest and suffered an altitude-induced heart attack. (His injury gets a brief mention in Into Thin Air.) Doctors advised against further mountain climbing. Rather than hang up his boots, Ginge simply capped his climbs at 6,000 meters—about 20,000 feet. While that rules out Everest and 16 other country high points he hasn’t climbed, he can sure as hell climb Agrihan.

Ginge, Gary, and I spend hours setting ropes between the two summits, which are connected by a 200-yard-long ridge made treacherous by a thousand-foot drop that goes straight into the crater. The traverse involves picking our way through the shrubs and trees that crowd the ridge, descending into a small valley, and then ascending a 15-foot mud wall.

The ridge is precarious—at one point while we’re pounding in anchor stakes, a three-foot chunk of mud peels off and falls away. We’re at least five days from a hospital, and if someone were to go over the edge, Ginge says, they’d be better off not surviving. John is wary of heights, making this particular scenario his nightmare. He doesn’t want to do the ridge traverse. The question is: Will he be able to sleep at night if he doesn’t touch both summits?

The next day, after the ropes are set, all 12 climbers make their way up to P960 and pose for a photo. Then, at their own pace, most everyone crosses the ridge to P952, just to be sure, and returns. But not John. Instead, he gives a little speech about how he woke up this morning feeling like he just didn’t need the second summit.

“Sometimes you need a mountain,” he says. “I woke up and I didn’t need this one.”

The ridge is precarious—at one point while we’re pounding in anchor stakes, a three-foot chunk of mud peels off and falls away. We’re at least five days from a hospital, and if someone were to go over the edge, they’d be better off not surviving.

On the way down, I ask another climber, Reid Larson, what to make of John’s decision. Reid is something of a high-pointing wunderkind. Just 32 years old, he’s been blitzing through lists and is now tied with John as the first person to summit all 50 states plus all five U.S. territories, assuming that P960 is the true summit. But if the other peak, P952, turns out to be higher, Reid, who touched both, will be the only one between them to have summited Agrihan. If this is John’s last expedition, why not be sure he’d really finished?

“Based on everything he’s done, it’s not really about risk aversion,” Reid says, referring to the ridge traverse. “We’re all sort of flummoxed.”

Of course, we don’t actually know that the second summit is higher. As near as we can tell, it’s somewhere between 18 inches and three feet taller than P960. But it’s awfully close. John may have already done the thing we’re worried he’ll regret not doing. But we may never get an accurate measurement.

Except that while the rest of us make our way down from the top, Gary Reckelhoff stays behind. We have another four days before the boat comes. He’s going to stay near the spotting scope and wait for the weather to clear, because “there can only be one highest point,” he says. Two days later the clouds part, and Gary reports that the second peak is seven feet taller than the one John went up. So it’s confirmed: John didn’t stand on the highest point.

Over the next two days, the team tries to convince John to go back up the mountain and touch the true summit. The trail isn’t that bad. Gary can get up there in four hours. John could do it in a day. We’d carry his gear!

Except that on the way down from the summit, ten minutes from base camp, Ginge slipped and landed on his machete, severing a tendon in his finger. Greg, the ER doc, sewed him up, but Ginge will need surgery and is done climbing for now. We’re trying to convince John to take on a death-mud traverse without the strongest climber on our team.

Or maybe it has nothing to do with Ginge. At one point or another, each of us is going to wake up to find that we can’t do the things we used to be able to do, or that those things don’t matter as much as they once did. For John, that day just happened to come when he was supposed to summit the last mountain on his list.

“I was making a statement to myself,” he told me later, recalling his decision not to go up again. “I need to stop the obsession.”

For the past 20 years, John has been the fixated-on-summits guy. It has colored every relationship, every interaction. People want to know: What’s next?

“I climbed Denali, and then everyone said, ‘Are you going to do Everest?’ ” John says. “Where does it stop? And how do you stop it?”

Maybe by pulling up just short of the true summit, and counting it anyway. John did 99.78 percent of Agrihan. Maybe it’s time to start rounding up. We swat flies and play backgammon for three days until the Super Emerald shows up to take us home. Agrihan recedes into the distance, and John raises his middle finger, flipping off the mountain, his youth, his desire to make history.

The only way to slay some dragons is to simply stop believing in them.

Contributing editor Peter Frick-Wright () is the host of the �����ԹϺ��� podcast.