Jesse Itzler’s Everest-Sized Hike Will Change Your Life

The former white-boy rapper and mega-successful serial entrepreneur has become a bestselling wellness author and Tony Robbins-style life coach. His latest venture, a highly social weekend of walking up mountains until you drop, called 29029, is pitched as a new breed of restorative endurance event. But is this just a brutal group hike with good marketing?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

“Some of you are scared,” says Jesse Itzler to the people sitting on the sunbaked terrace outside the soaring lodge at Utah’s Snowbasin Resort. “You should be.”

Nervous laughter percolates through the crowd, most of us giddy with prerace jitters, craft beer, and the effects of the 6,450-foot elevation. “You should have butterflies—that’s the sign of a good event,” says Itzler, who turns 50 today. He wears an ensemble that looks plucked from a casting call for the movie White Men Can’t Jump: capacious basketball shorts, outsize Hoka running shoes, and a headband restraining his curly hair. He lives in Atlanta these days but has retained his New York accent (Ros-lyn, exit 37 on the Long Island Expressway), as well as his aura of street-smart moxie.

Itzler wheels around to look at a dusky, jagged streak of earth—in winter, a ski run called City Hill—heading up the thickly wooded mountain. The grade tops out at around 50 percent, and in this August heat I’m tired just looking at it. Tomorrow morning at six, we’ll trudge 2,450 feet up that slope until we reach the summit lodge. Then we’ll take a gondola down and do the hike again. And again. If we want to reach our ultimate goal—hiking the equivalent elevation of Mount Everest—we will summit 13 times within 36 hours, covering close to 30,000 vertical feet and 30 miles.

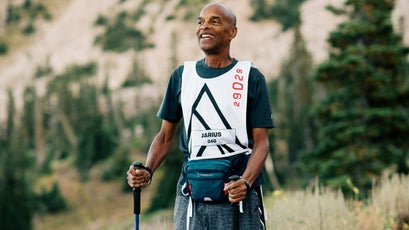

Welcome to , which the website calls a “new category of events,” one that is “equal parts physical, mental and spiritual.” For the 92 participants who have paid nearly $4,000 a head, it’s a weekend of glamping. It’s pre-event lectures from professional athletes, Olympians, and coaches. It’s post-event parties. It’s LinkedIn meets Strava. It’s a little bit TED and a whole lotta shred. And Itzler has a hunch that it may help change people’s lives.

The concept of 29029, which currently puts on two annual events and plans to expand, emerged from a particular confluence in the Venn diagram that is the life of Jesse Itzler. As an athlete, Itzler completed more than 20 consecutive New York City Marathons. As a rapper, he had a rather improbably successful career—for a Jewish kid from Long Island, at least—as Jesse Jaymes, cracking the Billboard Top 100 with the frat-rap anthem “Shake It (Like a White Girl).”

As an entrepreneur, Itzler “found the lane,” as he likes to say (a basketball aficionado, he’s part owner of the Atlanta Hawks), essentially creating the business of licensing songs played in sports arenas for CDs. After his first ride in a private jet, he helped forge a new market in private aviation (in the form of Marquis Jet, later sold to Warren Buffett’s NetJets). And as a runner looking for more effective hydration, he showed up early to the coconut-water game as a partner in Zico, which was eventually sold to Coca-Cola. “Endurance hiking,” as he calls it, could be the next big thing in the crowded field of endurance events.

“Don’t say it sucks,” yells Itzler. “Embrace it. This is what you paid for! For the next two days, there are no kids, no taxes, no e-mail—this is your job!

But to hear Itzler tell it, what he’s doing with 29029 isn’t simply about people smashing PRs or nabbing KOMs against competitors who remain anonymous behind bib numbers and performance shades. He talks about people stepping into the unknown, about struggling as a group, about walking away transformed. Last year he started an online coaching course called Build Your Life Resume, named after his conviction that it’s the things people do in life that don’t slot neatly onto a résumé that provide the truest measure of who they are. One of those things, in his mind, is climbing the equivalent of Everest with a bunch of strangers.

“Some of you are going to be deflated,” he says, gesturing to the hill. “You’re going to think, I’ve been doing this for 20 minutes and I’m only here—I could throw a rock and hit the lodge.” He pauses. “But you don’t think like that. You think in the moment, you keep chipping away. And when you’re tired—thinking, Man, I’m going to go hang out in my little tepee tent—no, you do it again. That’s what you’re here to do.”

Now he’s on his feet, bouncing a bit with each sentence, throwing down like the rapper he once was. “It’s a �ɲ����������������!” he implores. “We’re hiking. It’s a long time! It just comes down to: Do you want to keep going or not? This is an adventure, and there’s two ways to look at it when you get up there. This sucks, or, whoa, excuse me, who the fuck am I?” What people do in the next 36 hours, thinks Itzler, will recalibrate their sense of the possible. “Don’t say it sucks. Embrace it. This is what you paid for! For the next two days, there are no kids, no taxes, no e-mail—this is your job! Returning an e-mail, are you kidding me? That’s easy!”

Before there was the mountain, there was The Hill.

The incline in question lies behind the house on Connecticut’s Candlewood Lake where Itzler and his wife—Sara Blakely, the onetime fax-machine seller who turned the women’s undergarment startup Spanx into a billion-dollar business—and their four young children spend their summers. It’s a steep sward that plunges from the back of the house to the lakefront.

One afternoon six years ago, Itzler and a few friends decided—for no better reason than the protagonist of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer” had in swimming all the pools in his affluent suburban town—to run up and down that hill as many times as they could.

“We did ten and we were gassed,” he says. Itzler asked his companions: “Do you think anyone can do 100 of these things?” The general consensus was no way. “I said, What are you guys doing August fourth?” That sporting lark has since blossomed into a much anticipated, wait-listed annual event called . “There’s food trucks, tents, chip timing. All the boats pull up,” Itzler says. The record—100 laps in an hour and 40 minutes—is held by someone named Kevin the Cop. “It might be the best backyard race in the world!”

He tells me this as we sit, on a sultry July afternoon, in a sunroom overlooking the lake, joined by Marc Hodulich, his partner in 29029. The vibe is chill. There’s no PR minder, and Itzler is wearing his preferred uniform of shorts and a T-shirt. His personal chef has decamped back to Atlanta, so he has brought me a sort of smoothie bowl consisting of bananas, dates, blueberries, raw honey, and almond milk. I accidentally dump too many walnuts into the concoction, and Itzler says, soothingly, “Oh, that’s OK. Nothing can happen here.” Every so often, he punctuates his conversation with a shout: “Go, Tank!” Out of sight, on the hill below, Itzler’s chief operating officer, Marc “the Tank” Adelman, is steaming up the hill, in training for the upcoming Hell.

The idea of 29029 began to take shape in 2016, after Itzler met Hodulich in Atlanta at his kids’ flag-football practice. Hodulich, a onetime member of the Auburn University track team, had a habit of running to practice, which caught Itzler’s attention. Hodulich, it turned out, owned a business that put on athletic events. While working as a management consultant, he had created the Wall Street Decathalon, which he describes as a kind of “NFL combine for the average guy.” He had also taken the beer mile—an old track-team tradition of drinking a beer every quarter mile and seeing who could notch the fastest time without hurling—and turned it into a commercialized mass event. (“It was total boom-bust,” Hodulich says, with attendance soaring from a few hundred to several thousand.)

They started talking: Could Hell on the Hill be something bigger? Neither man wanted to create just another race—a solitary, punishing ultrarun or costumed 10K. They craved doing something accessible, something both challenging and doable. And something about more than just the challenge itself.

It was a theme Itzler had been exploring in his own life. In 2015, he published , a book that took shape after he saw retired Navy SEAL and ne plus ultra hardman David Goggins soldier through a 24-hour endurance race “with a sense of purpose I couldn’t quite comprehend.” Later, Itzler invited him to move into his family’s Manhattan apartment for 31 days of physical brutality and life lessons. This year, Itzler published Living with the Monks, his account of the two weeks he spent with an Eastern Orthodox order in upstate New York. The goal, he wrote, was “to help me quiet my mind and create a new kind of edge.”

Everesting, an idea previously associated with the semi-underground pursuit of climbing that peak’s elevation on a single bike ride, had a suitably monumental feel. Everest was a powerful brand in itself, an instantly recognizable logo on the landscape of the imagination. From here, Hodulich says, Itzler’s marketing acumen took over—maybe, he thought, they could stage a challenge that was really hard, but one that participants could take on in a group setting.

“For three days, we’re a community,” Hodulich tells me, “eating meals together, sharing tents with strangers, bonding on the mountain.” Put people together under hardship, the thinking goes, and connections will form.

All this fits neatly into the larger world of . Itzler’s eight-week online coaching program starts at $495 and covers, via conference calls and Facebook Live sessions, four “buckets”—business, wellness, relationships, and mindset. One of his tenets, Develop a Won’t Stop Mentality, sounds tailor-made for 29029: fitness or lung capacity per se isn’t going to be what keeps you from reaching your goal; much of it comes down to mindset. “What I love about this,” Itzler says, “is that my wife, who’s not an endurance athlete, can go out there and just gut it out.”

At this point, after a run up the hill and a swim in Candlewood Lake, Itzler and Hodulich and I have repaired to the steam room— the very steam room, in fact, where Goggins had once subjected Itzler to a 125-degree scalding. (“Now I know how a Hot Pocket feels inside a microwave,” Itzler wrote in Living with a SEAL.) We hit a mere 115—the point at which the human body loses the ability to cool itself—but it feels like my contact lenses are melting onto my eyes.

Later we hit the outdoor plunge pool, chilled to precisely 52 degrees. (Itzler is a man who loves water, and who loves temperature extremes.) While we’re soaking and freezing, Hodulich tells me that at some point during 29029, every participant is going to feel “the suck.” The fitter athletes will go longer before feeling it, of course. But, he says, “Everyone’s going to reach that point. The beautiful thing about this event is everyone’s going to get to where the mind opens the door to quitting, and you have to decide whether to let the body go through with it, or not.”

At Snowbasin, that door begins to open for me on my fifth lap. I’m not thinking about dropping out entirely, but suddenly, in the late-afternoon heat, with mild twitches of dehydration and my tendons straining from the goatlike scrambling, I begin to question doing 13 summits. Other, well-adjusted people are targeting nine, the equivalent of climbing Denali. Isn’t that enough? Everest is starting to seem like overkill.

And 29029 makes it easy to quit. “Every time you get off the gondola at the base, you have the choice to make a left turn and go to the tents, or to turn right and go back up the mountain,” Hodulich had said. “You want to drop out of an ultra at mile 70? Good luck walking to the aid station.” Once people started up the mountain, he said, they never walked back down. The first steps were often the hardest, but they were cast in concrete.

At the first 29029, held last year in Stratton, Vermont, 58 percent of the 150 or so participants managed to Everest, while some people needed to be rehydrated by IV. But everyone can choose their own goal in the Snowbasin race, beginning with Mount Kosciuszko (Australia’s highest peak), which requires four laps. At the base of the mountain after each climb, participants use a hot cattle brand to burn the 29029 logo beside their name on a leaderboard. “It’s very visceral,” says Hodulich. “You start thinking about burning the wood each lap.”

I had imagined hiking up a ski hill to be a simple cavort up a series of grassy knolls. But not long after the start signal goes off and we begin to climb City Hill, our headlamps stabbing the crepuscular gloom and our trekking poles clicking like insect legs, reality dawns. The hill is steep. It is rocky. There is straw scattered about, and it’s moist with dew, making things slippery. Soon the sun will be out, and with zero shade it will be hot. Inexplicable swarms of grasshoppers blitz past. My lungs, accustomed to life at sea level, are already feeling oxygen starved. A small pack surges ahead, led by Olympic triathletes Joe Maloy and Greg Billington—and Kevin Krause, a.k.a. Kevin the Cop, hero of Hell on the Hill.

Itzler was right. This is no starter race. This is going to be hard. After a while, I settle into an even pace behind a lone woman. We’re soon stranded between the elite pack and everyone else. We finish the first ascent in about an hour, skipping all the on-course aid stations save the one at the summit. When we get in the gondola, I learn that my companion is Melanie Sherman, a 34-year-old analyst based in Scottsdale, Arizona, with the drugstore chain CVS. An Ironman competitor, she’s been unable to race for the past six years due to autoimmune issues. A random podcast led her to Jesse Itzler and Build Your Life Resume.

“I’ve done all kinds of leadership and training courses,” she tells me, “but this is top-notch.” When the first program ended, she says, “I was so disappointed—I was like, There’s going to be a piece of me missing not to have Jesse in my ear.” She has since signed up for a new yearlong program Itzler created.

During the event, I hear those sorts of testimonials a lot. People were taking the online course or had read SEAL, as Itzler’s first book is commonly called, or they had heard him on the Rich Roll podcast. One guy, the owner of a 3-D printing company, brought a group of employees as a team-building exercise. An anesthesiologist from North Carolina heard Itzler on a popular investing podcast. About one in five guests are repeat 29029 attendees. One man says he lost a lot of weight while training for the event, but he’s still unsure whether he can complete a single summit.

As the day wears on, I begin to appreciate the Zen-like simplicity of the whole thing: walk up, ride down, burn your peak into the board, walk up again. Heat and altitude are taking their toll, however. During lap one, the first rest stop had seemed laughably close. But by climb six it hovers forever in the distance, a mirage of Gatorade and cold sponges. Aid stations are like desert watering holes, where we trade tips and gossip: Did you hear that Steve Weatherford (the former NFL player) killed a rattlesnake on his inaugural lap? Did you hear about the moose near the Porta-Potties? There is drama: a brief lighting storm closes down the gondolas, stranding some hikers at the summit lodge.

I take a break for dinner and have a brief rest in one of the NormaTec zero-gravity chairs in the recovery room. “The mental fortitude you get from this, you can’t touch it,” someone is saying. “You’re not going to get this from a book or a class.” I nod in agreement, then fall asleep.

A bit later, I don my headlamp and strike out for lap seven. I soon encounter Itzler, along with my talisman, Melanie Sherman, at an aid station. As we trudge upward, occasional shouts of “Go Jesse!” ring out from the gondolas overhead. He raises his trekking pole in reply. Itzler has brought all these people to the mountain, and he seems determined that they get up it.

At around 11 P.M., I stagger back to my tepee, having ascended the equivalent of Vinson Massif. (It’s in Antarctica.) I will have to knock out 13,000 more feet by 6 tomorrow evening.

Some participants opt for sleep, while others march on through the night. At 3 A.M., Geeta Nadkarni, a business coach from Montreal, is still on the hill, just beginning her seventh lap. She wanders off the trail at times. She sees the reflective eyes of animals. She FaceTimes her husband and kids for reassurance. “Every piece of me,” she tells me later, “wanted to take an Uber down.” But, she says, “Your subconscious creates your reality. If I crossed the start line, I was going to finish that hike.” She finishes with ten laps, one more than her original goal of Denali.

For me, the next morning has a louche, unwashed feeling to it, like waking up hung-over in the bed of an ex that you swore you’d never see again. But with an “I can’t go on, I will go on” sort of blind determination, I start climbing. The laps stretch longer each time. Hodulich, who seems to be everywhere, advises me not to break. Just start walking, he urges—you don’t have a reverse gear. The recovery room, he adds, is the enemy. Lunch is the enemy. Time itself is the enemy. Each lap is now consuming several hours, with longer breaks in between. Then, finally, by midafternoon, with the sun at its zenith and my spirit at its nadir, I have it: the coveted red bib with the words Final Ascent on the back.

Looking back, 29029 was hard—mentally more than physically. My heart rate never got into the red, but my psyche did, as I struggled to convince myself to climb the same hill for the tenth time. As people hiked up the mountain, they encountered the very sorts of lessons Itzler was trying to get across in his online course.

On the event’s private Facebook page, people traded war stories and shared lessons. Babak Azad, the founder of a marketing company, wrote about hiking in the dark. “As much as we could look up a bit ahead of us, we couldn’t see the rest of what lay in front. And sometimes that’s a good thing. Knowing the goal is important but sometimes just how big it is can be more than daunting.” He also noted that, though everyone knew it wasn’t a race, those with specific goals couldn’t help but notice the progress of others on the leaderboard. “Sometimes, and this is the part that sucks,” Azad wrote, “when you’re sleeping, someone else may still be climbing the mountain.” Is there a more apt summation of modern life?

At the post-event awards ceremony, an enthused Itzler, mic in hand, warmed up the crowd: “Who feels like they’ve been here a year and a half? We’ve been here 41 hours.” “Whose brilliant idea was it to put up the ‘two more miles’ sign?” And: “Excuse my language, but where the fuck did they get all these grasshoppers?”

Then he grew more serious. “I remember last night,” he said, “there were two people on the course hooked up to full oxygen, with blood-pressure monitors on their arms. These guys looked terrible. And then today, they’re on the hill!”

By everyone’s reckoning, Utah was harder than the Vermont event had been. Whether it was because of the heat, the altitude, or the climbing conditions, only 38 percent of the participants Everested. But by another metric, the event was a success. “Don’t take this the wrong way,” Itzler said, “but if you had lined everybody up and said that we’re going to do a 36-hour ultramarathon event where we cover thousands of vertical feet on a really steep incline, in 80-degree heat, and have 100 percent of the attendees complete one of the Seven Summits, I’d have said, ‘No chance. Get more medics, Marc’—that’s what I would have said. People dug in so hard. I’m in awe.”

We all have an extra gear within us, Itzler wanted us to know. The supreme grace of endurance events is that time spent at the extremes suddenly redefines what you thought was hard in your life. And we’d all been through something together, on the mountain, that others just would not get.

“Don’t try to explain this to anybody at home,” Itzler said. “You say, ‘I did this thing, it was really hard.’ They’re like, ‘Oh, a hike on a mountain.’ ” They won’t know, he said, “how it felt, in the heat, on a course that never seemed to end, when you had three summits and you had ten to go. They’ll never understand it.”

Contributing editor Tom Vanderbilt () wrote about minimalism in September.