Last month, I had two goals for a nine-day backpacking trip in Yosemite National Park. First, to simply enjoy what is likely to be my only solo trip in 2018. This year I will spend about 55 nights out, but the bulk of them will be on guided and private group trips that come with responsibilities and compromises that solo trips do not.

And second, to scout the . I went in open-minded, uncertain if it would even be merited by the topography and terrain. But I suspected it was and hoped I would finish with a sense for exactly where it should go (and not go) and how it could be best completed as a thru-hike and in sections.

I hiked the Pacific Crest Trail through Yosemite in 2006 and 2007, on the Sierra High Route in 2008, and on the John Muir Trail in 2011. But I didn’t appreciate Yosemite’s true grandeur or size—or realize the potential for a stand-alone high route—until 2012, when I led three weeklong trips into areas I’d never been, like the Clark Range and the upper canyons of the Tuolumne River.

The Process

Development of a high route takes time. It starts with research. In this case, poring over topographic maps and Landsat imagery in , filling in details with the help of and , and consulting rangers and other avid Yosemite backcountry users. Personal familiarity with the area made this step much more efficient—I already knew where to start looking.

Then, the fun part: weeks or months (depending on your pace and the route length) in the field, hiking a preliminary route and alternates (some of which will prove superior and become the recommended route), forward and backward, in different seasons (and, eventually, in different years), with other people of different abilities, and at least once in its entirety.

Finally, there is the guidebook, which is a project of its own. I expect that a complete first edition—with preparatory information, a route description, data sheets and maps for a thru-hike and section hikes, and a rudimentary GPX file—will require 100-plus hours to produce. (It’ll be a good winter 2018–2019 project.) As more user feedback comes in, a revised second edition becomes necessary.

Overall, it’s a lot of work, and time-wise it’d be more financially fruitful for me to focus on other projects, like guiding trips or writing product reviews. But I love every step of the process and would do it full-time if I could.

Overview: Yosemite High Route

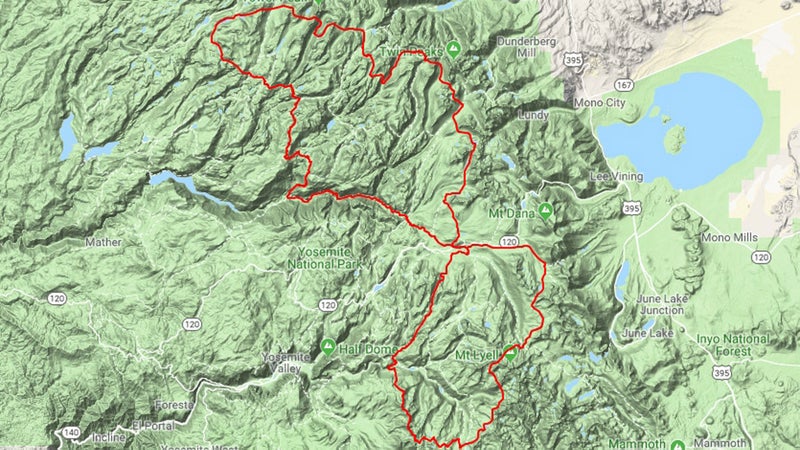

Where the boundary of Yosemite National Park overlaps with the Sierra Crest, from Dorothy Lake Pass in the north to Rodgers Peak in the south, there exists a world-class high route around the upper headwaters of the Tuolumne and Merced rivers that stays entirely within the park.

South of Rodgers Peak, the park boundary straddles the divide between the upper Merced and the North Fork of the San Joaquin, two major westbound rivers. This topography remains conducive to a high route to Triple Divide Peak, beyond which the watershed divide and boundary fade into less interesting foothills.

Thankfully, here the seldom visited Clark Range T-bones the boundary, providing worthy terrain for another ten miles.

North and west of Dorothy Lake Pass, the park boundary roughly follows the watershed divide between the Tuolumne and Clavey rivers, the latter of which drains the Emigrant Wilderness. I spent one day in this area and found it to be wild and pretty but not sufficiently dramatic. Perhaps it will be offered as an extra-credit segment.

So, “the good stuff” (understatement) on the Yosemite High Route runs for about 95 miles and lies between:

- Grace Meadow, in upper Falls Creek, a few miles downstream of where the Pacific Crest Trail exits the northern park boundary at Dorothy Lake Pass.

- Quartzite Peak, at the north tip of the Clark Range, which presents a commanding view of the Cathedral Range across the Merced and downstream into Yosemite Valley.

The route is majestic, remote, and largely off-trail but still technically practical for a backpacker. It shares just one pass with the Sierra High Route, developed by Steve Roper, and utilizes the Pacific Crest Trail/John Muir Trail for only a half-mile. The wilderness experience matches and sometimes exceeds that of other established high routes like Roper’s, the Kings Canyon High Basin Route, Wind River High Route, Glacier Divide Route, and the Pfiffner Traverse.

Tioga Road (CA-120), the east–west tourist highway that traverses the park, splits the Yosemite High Route in half. At Tuolumne Meadows, a broad plain at 8,500 feet through which the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne River meanders, there is a wilderness permit station, post office, store and grill, and multiple trailheads.

The dilemma that I am currently pondering is where to start and end the route. Logistically, Tuolumne is the best option. From there, the route can be undertaken as a north loop or south loop, or in its entirety in a figure eight. In this latter case, Tuolumne can serve as a midtrip resupply.

Qualitatively, Tuolumne is probably the rightful southern terminus, too. An excellent low-use route via Echo Creek can be followed for 15 miles to the base of the Clark Range, avoiding the dusty stock highways over Cathedral, Tuolumne, and Vogelsang passes. The alternative is Yosemite Valley, but I’m reluctant for many reasons.

The northern terminus is up for debate. The two closest options are on Highway 108: Leavitt Meadow and Sonora Pass, at 17 miles and 21 miles, respectively. It’s a bit farther—23 miles—to Grace Meadows from Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, but it’d be an easier hitch or shuttle. Finally, from Tuolumne Meadows, there are two possibilities, both 48 miles: the Pacific Crest Trail and the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne.

I chose the Grand Canyon, because Tuolumne Meadows is the most logistically convenient option, and because I, probably like most other prospective Yosemite High Route hikers, have already completed the PCT through the park. Even in late August after a dry winter, the Grand Canyon is spectacular, with countless waterfalls, lovely riverside camps, and imposing granite walls.