By the end of the century, sea level rise could wipe out millions of homes and force us to relocate some major population centers. This has been accepted science for decades, and we’re beginning to see the effects today. But just like we’ve gotten used to the idea of a Florida man standing knee deep in water while being interviewed on the news, it’s also now a common sight to turn on the TV and see a family standing in front of their burned-out home.

It’s time to start thinking about climate-change-induced wildfire in the same way we do flooding.

How Climate Change Worsens Wildfires

The between a warming planet and the increased threat of wildfires begins simply and logically: higher temperatures create drier forests, and drier forests are more at-risk of burning. But the connection gets more complicated from there.

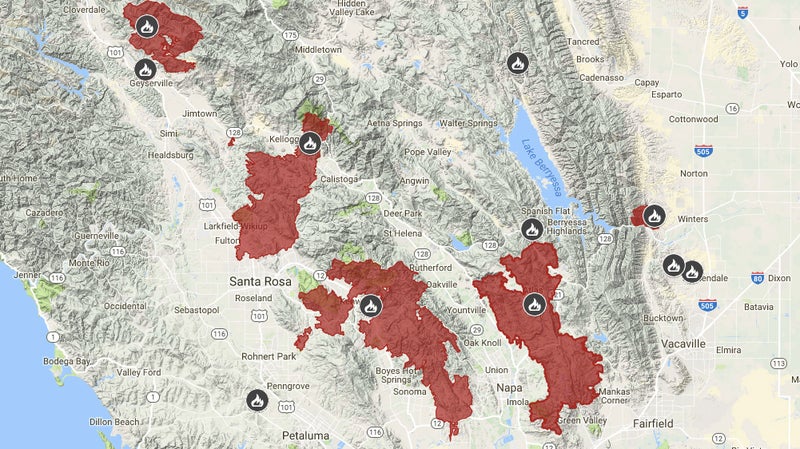

I first started delving into the connection between higher global average temperatures and wildfires in the western U.S. as I researched an article that was eventually called “Why the West Is Burning.” I wrote that before the catastrophic fires in northern California destroyed entire towns, and as I was putting it together, the scale of the threat began to feel both menacing and personal.��I was up at my girlfriend’s cabin in the Sierra Nevadas, not far from Napa and Sonoma, and we were surrounded by millions of dead trees. Literally: the 10-year drought in California .��

Despite the drought, . That led to booming growth of grass and brush, which then dried out and died as . Massive quantities of dry kindling piled up under millions of dead trees? You couldn’t create a better recipe for wildfire.��

Just like flooding is turning out to be vastly more complicated than simply a slow, linear encroachment of the ocean onto formerly dry land, wildfire is also much more than a simple case of higher temperatures leading to drier fuel. Extreme weather like summer droughts and winter storms introduce unpredictable variables into the fire equation, even while the slow northerly creep of hot, dry weather increases the range of places at risk of wildfire.��

On top of that, fire has the potential to accelerate the pace of climate change. Massive wildfires release huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. As the warming planet thaws out the Arctic, for example, that region is expected to see 30 percent more . Fully half of the world’s soil carbon is stored in the Arctic permafrost, so in addition to the carbon released by burning the tundra, those fires will contribute to the release of carbon in the soil. Once in the atmosphere, that carbon release will lead to more fire.

Starting to understand my sense of dread?

How Bad Will It Get?

Diagonal lines on graphs didn’t prepare us for a major hurricane hitting New York and New Jersey or Houston or Puerto Rico.��And fire is proving to be just as difficult to predict as flooding. Still, the data we do have sure is ominous.

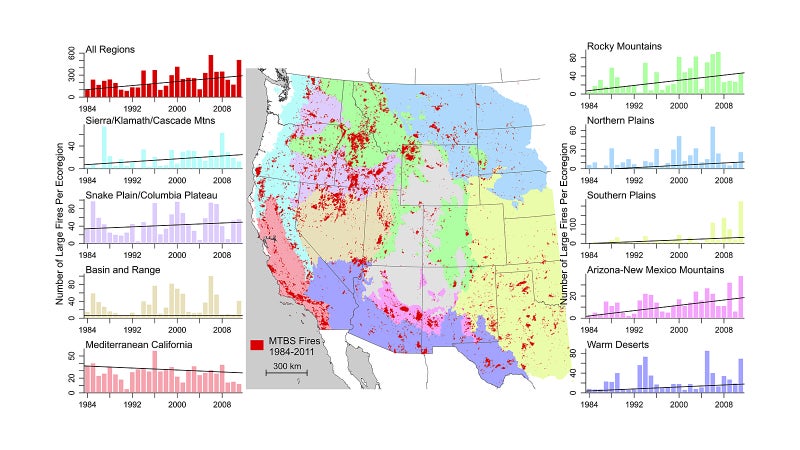

—the same report that created headlines two weeks ago when it —paints a bleak picture of our future. “The number of large fires increased at a rate of seven fires per year, while total fire area increased at a rate of 355 km2 [221 square miles] per year,” reads . The numbers refer to large (greater than 1.5 square miles) wildfires in the western U.S. between 1984 and 2011.�� cited by the report found that the area burned by wildfires in the West doubled between 1984 and 2015.

Regional increases are as stark as the national one. Another concludes that very large wildfires (78 square miles or more) in the Pacific Northwest will more than double in frequency by 2060. The report pays particular attention to Alaska, where fires in the Arctic tundra stand to release those vast amounts of soil carbon. The research concludes that the chances of fires over 386 square miles in size in that region will increase by a factor of four by the end of this century. The total area burned each year may increase by up to 53 percent in the same time. That’s of Alaska that are predicted to burn each year by 2099.

Quantifying the Threat

Aside from smoke-filled air, blackened forests, and campfire bans, I wanted to learn how this much-worsened incidence of wildfire would effect my life. In short: Will my house burn down?

in the Los Angeles Times helped me understand the scale of the threat. The writers reported that, in southern California alone, at least 550,000 homes are currently at extreme risk of wildfire. At-risk areas are defined by local governments using a variety of standards. If you standardize the methodolgy that numbers rises by another 455,000. That means a million homes, and millions of residents, live under near-constant threat of wildfire—and we’re just talking in SoCal.��

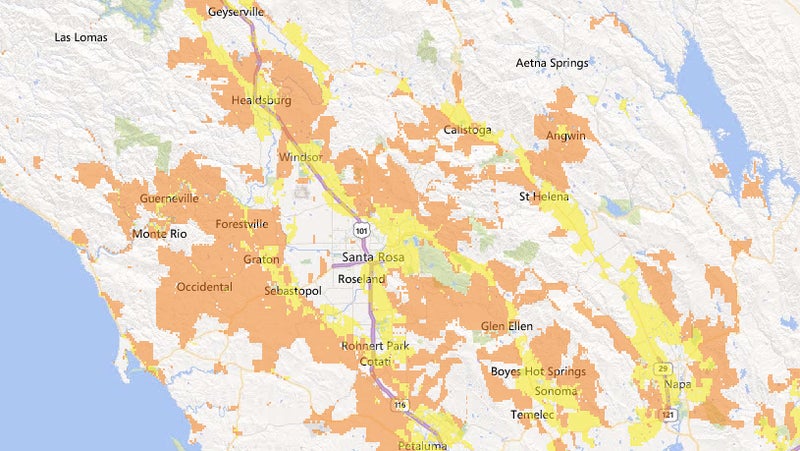

That article led me to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, whose has been studying wildland-urban interface.�� defines that term: “The wildland–urban interface (WUI) is the area where houses meet or intermingle with undeveloped wildland vegetation. The WUI is thus a focal area for human–environment conflicts, such as the destruction of homes by wildfires.”

The lab has nationwide, and determined that . In California alone, that number is 5.1 million. Given what happened in Santa Rosa last month, we’ve now seen that wildfire can destroy homes in even dense, urban areas in the state.��

Comparing NOAA sea level rise maps shows that nationwide 1.9 million homes are at risk of being underwater by 2100. In California, that number is 42,353. That means in California alone, 120 times more homes are at risk from wildfire than from sea level rise.

Adapting to Change

We’ve been aware of the scale of the problem represented by sea level rise for decades. on Last Week Tonight a couple of weeks ago, the federal government has been trying to help people move away from low-lying coastal areas since the 1970s. But we don’t have anything like that level of awareness about the increasing threat of climate-change-driven wildfire.

In fact, the pace of development in areas threatened by wildfires is actually increasing. Over . In the 13 western states where that means those homes are at extreme or high risk of wildfire, . “People enjoy building houses in beautiful places where they are surrounded by the beauty of nature,” the University of Wisconsin lab puts it simply.

We’re re-thinking where and how we build due to sea level rise, even modifying existing houses and businesses to cope with it. People know that living at the beach is going to have consequences. People need to know that living in the mountains or in other areas prone to fire is going to have consequences, too.

The U.S. Forest Service last compiled in 2014. Is your home on it? Four of our family's are.��