Lake Superior Is Our Most Overlooked Playground

Famously cold and frighteningly massive, Lake Superior contains 10 percent of the world's surface freshwater, holds the remains of 6,000 shipwrecks, and offers a lifetime of adventure. Stephanie Pearson sets out to circumnavigate America's most overlooked playground.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

It’s 12:56 a.m. and I’m spiraling down a rabbit hole of fear. There are the yellow ATTENTION: BEARS IN THE AREA. USE CAUTION signs plastered everywhere. Through my tent flap, lightning is illuminating swaying pines, which are bending with such ferocity that they sound like crashing waves. But my biggest worry lies a 15-minute walk away, down a mossy forest path—Lake Superior, a body of water with an average yearly temperature of 40 degrees, notoriously strong currents, fickle weather, and 25-foot waves that can sink massive ships.

I grew up in Duluth, Minnesota, within five miles of the world’s largest lake by surface area, and it has always seemed bipolar to me—sometimes serene, sometimes deeply destructive, always unpredictable. Summertime is as hospitable as the lake gets, and for the past few days it has been exceptionally mellow. I’m on the lake’s northeast shore exploring , hiking empty backcountry trails, eating smoked trout on sand beaches backed by wave-sculpted granite, and camping at Hattie Cove Campground. Tonight’s electrical storm came out of nowhere.

Morning brings relief. I zip out of my tent and greet an unusually hot and calm day. For the next few hours, three park employees, author Ruth Fletcher, her husband, Ward Conway, and I follow the 84-mile park shoreline in a powerful 30-foot search and rescue boat. It has shock absorbers on the front seats to withstand a pounding from waves. Today, however, the water is so placid that we’re speeding effortlessly past fjords, thunderous waterfalls, empty beaches, and defunct lighthouses.

I’ve spent the past 20 years writing about far-flung places, from Tasmania to Bhutan, and here I am awed by one of the most pristine, wild, and hard-to-reach regions in my own backyard.

“You can’t get here unless the lake lets you,” says Fletcher when we land on a crescent-shaped beach at the mouth of the . This is Lake Superior’s most remote point. There are no roads for 50 miles in any direction. It’s also the site of Fletcher’s book, , an account of the 1920s logging camp where her father lived as a boy. More than 200 residents logged thousands of cords of timber in this area, until the stock market crashed in 1929 and the camp was abandoned. All that’s left is a decaying log cabin surrounded by daisies, disintegrating leather shoes, discarded glass bottles, and mounds of bear scat.

Fletcher is here to familiarize the park’s staff with the area’s history. As she and Conway search the bush for a memorial plaque, installed by the park in honor of her father, I wade up to my knees in water so cold that it makes my calves spasm. I’ve felt that chill since I was a child splashing around on Park Point, a seven-mile sand beach in Duluth. I’ve spent the past 20 years writing about far-flung places, from Tasmania to Bhutan, and here I am awed by one of the most pristine, wild, and hard-to-reach regions in my own backyard.

“If someone were to live here now, in some ways it would be even more remote than in my father’s time,” Fletcher tells me. “The only way out in the winter would be to dogsled 70 miles inland to White River.”

Pukaskwa is the only wilderness-designated park in Ontario, an impressive distinction in a province that has about 1,000 polar bears, more than 250,000 lakes, and one person per square mile in its entire northwest region. With a single road in, surrounded by backcountry so dense that few people other than its have seen it, the park is a favorite of expert kayakers who paddle Pukaskwa’s raw coastline and backpackers who know they need at least ten days to hike the out-and-back 37-mile coastal trail.

That kind of toughness sums up the steely character of most folks who have lived along Lake Superior over the centuries—from the Ojibwe to the French voyageurs to Nordic immigrant fishermen.

Everyone except, perhaps, me. I can count on two hands the number of times I ventured off Lake Superior’s shoreline growing up in Duluth. In the winter, when the air temperature dropped below zero, steam would rise from the lake, shrouding the city in magical puffs of white. But on the dreariest days, the lake would reflect the lightless, bruised sky, so dark and heavy that I felt like it was crushing my spirit. My family didn’t have a boat big enough to safely navigate such a dangerous body of water. Its inaccessibility made Superior that much more mysterious—like a giant mood ring reflecting the temper of the universe. Even on the most benign summer days, its power was omnipresent. Once, while landing my sister’s kayak on a rocky beach in five-foot waves, I capsized and hit my head. It made me wonder if the lake was a living entity, actively trying to kill me.

As an old high school buddy told me before I set off, “Looking into Lake Superior is like looking into the eye of God.”

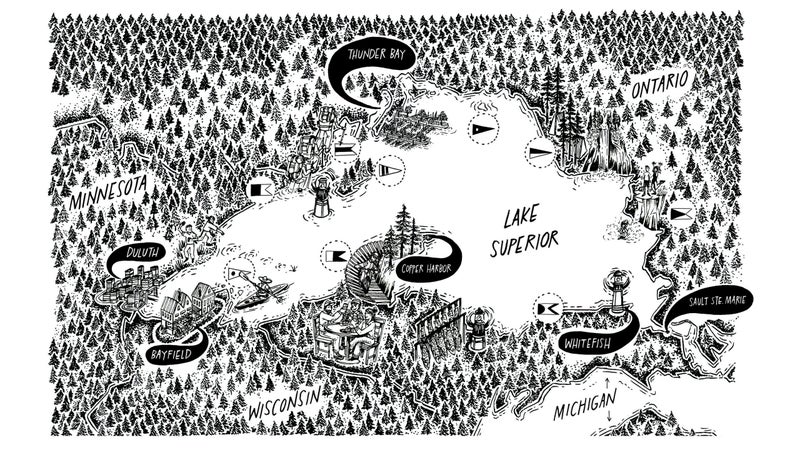

After 20 years living out west, I recently moved home to Duluth, and I’m finally ready to embrace Superior, no matter her mood. I plan to spend three weeks circumnavigating the lake, driving clockwise up Minnesota’s north shore, camping in the national and provincial parks along the Ontario coast, then driving Michigan’s south shore back to Duluth, for a total of 1,300 miles. I’ll camp, kayak, and catch rides on sailboats, research vessels, fishing skiffs, and powerboats. It’s more than geography that drew me back north. I also missed the rugged authenticity of the people. No one can fake a love for the outdoors in a region where temperatures dip below zero for weeks each year.

and would agree. Before leaving Duluth, I meet up with them on a drizzly, 50-degree June morning. They’re in Wilkie’s Volkswagen bus in a parking lot at the mouth of the Lester River, waiting for a storm to firm the soupy chop into rideable waves at the Rock, a popular left break. But the chop isn’t cooperating.

“Surfing on Lake Superior is a spiritual experience,” says Wilkie, a contractor who grew up in Anaheim, California. “That’s why I registered my surfing page on Facebook as a religious organization.”

“The best waves are in the winter,” he says. “I’ve surfed in December in negative-30-degree weather with windchill. We had icicles on our beards. As soon as the water hits, I get ice cream headaches and feel like I’m going to die.”

It’s reasonable to question these surfers’ sanity: I’ve seen the lake shatter skating-rink-size slabs of ice against the rocky shoreline in winter storms.

On the dreariest days, the lake would reflect the lightless, bruised sky, so dark and heavy that I felt like it was crushing my spirit.

The volume of the four lesser Great Lakes plus three more Lake Eries combined, Superior may be only 10,000 years old, but the bedrock along its north shore dates back 1.2 billion years. The Anishinabek and their descendants have been living around the lake almost as long as it has existed, mining copper deposits from Isle Royale to the Keweenaw Peninsula, paddling in birch-bark canoes, and trading furs with the Europeans soon after arrived around 1622. Today fewer than a million residents live within its basin. By comparison, Lake Michigan’s has a population of more than 12 million.

Because it’s so pristine, Lake Superior is increasingly valuable—for both its water and its recreation potential. With 2,726 miles of shoreline (including islands) stretching across three states and one Canadian province, it borders five national parks in the U.S., one in Canada, and roughly two dozen state and provincial parks. , is the least visited national park in the lower 48. In Ontario, the , approved in 2015, will place 13 percent of Lake Superior water—including the fish and more than 600 islands—under protection.

Lake Superior’s shoreline contains everything from thousand-foot cliffs, miles-long white-sand beaches, and vast, empty wilderness up north to deciduous forest and caves carved from 500-million-year-old limestone on its southern side. All together it’s a giant, world-class playground for hiking, trail running, mountain biking, kayaking, sailing, backcountry camping, and open-water swimming (for anyone crazy enough to try).

“Duluth has a legend that Lake Superior doesn’t give up its dead,” Isaacson tells me.

Actually, it isn’t legend. It’s scientific fact. Lake Superior is so cold that if a person dies in it, his or her body is unlikely to resurface. The bacteria that makes a body float grows too slowly here.

July and August are Lake Superior’s most serene months, so I pull out of my driveway at 5:01 a.m. on July 14. As I drive north on Scenic Highway 61, the lake is flat. That’s good, because at 5:30 I meet fisherman Stephen Dahl at the Knife River Marina, and we putter a half-mile out in his 18-foot, handmade, steel-hulled fishing boat powered by a 25-horsepower Yamaha.

Dahl has a robust build and a bushy beard that makes him look like a Viking in flame orange waders. He holds one of only 25 highly coveted commercial fishing licenses for the lake’s 189-mile-long Minnesota shoreline and has been net-fishing for herring and lake trout seven days a week, from April through December, for the past 28 years.

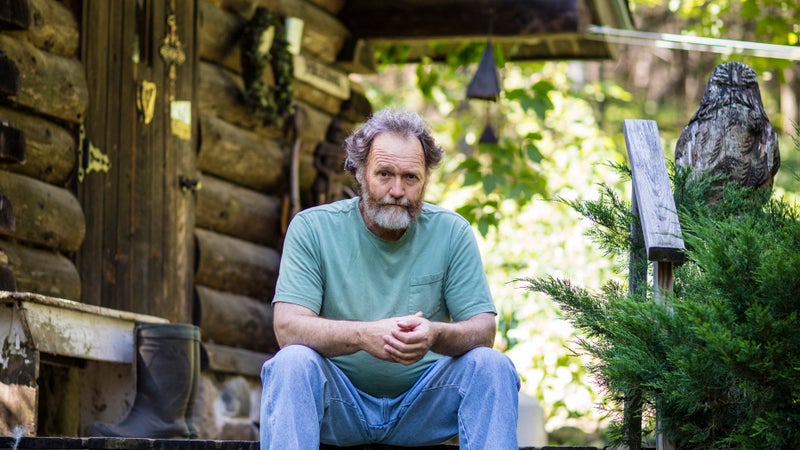

There are 34 native and 18 non-native fish species in the lake, and the fishery is strictly managed. Dahl had to lobby multiple government organizations for years to get his 5,500-per-year lake-trout quota. In the off-season, Dahl, who studied Scandinavian literature in Copenhagen, builds harps for his wife and writes poetry in his log cabin. The only technology he carries in the boat today is a globelike compass patched together with electrical tape.

“I don’t use a GPS,” he tells me. “It’s just another electronic piece that’s going to get wet and smashed.”

We’re out here at dawn because it’s the calmest time of day. The wind and waves will soon pick up, which is why now is a good time to internally review the one-ten-one rule of cold-water immersion. People wearing flotation devices who are submerged in water colder than 59 degrees have one minute to recover from the shock, ten minutes before losing effective use of their limbs, and one hour before losing consciousness due to hypothermia. Twenty percent of submerged people die in that first minute—with or without a personal flotation device. Luckily, there’s no fog today. If I was to fall out of the boat, I figure my chances of surviving a swim to shore would be 50/50.

Dahl can haul in up to 1,000 pounds of herring in one of his two 300-foot fishing nets—a technique that hasn’t changed since Norwegian immigrants started fishing this shoreline in the 1880s. Lake Superior’s herring stocks fluctuate, but the lake trout have recovered nicely since a sea lamprey infestation almost decimated the fishery in the 1960s. Dahl’s livelihood depends on his daily catch. Today, after an hour, he has hauled in a single foot-long lake trout that he categorizes as “tinier than tiny.”

“I have some crazy Nordic genes running around in this body,” he says. “Some days I come out here and get beat to hell, but it gets in your blood. The beauty of Lake Superior is the cold. It’s a real simple fishery because it’s so sterile. Being cold doesn’t scare me. What scares me with Lake Superior is the warming planet.”

That has a few people worried. Before leaving Duluth, I spent a day on the Blue Heron, a research vessel for the , which could be considered the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution of freshwater. The boat is structurally identical to the Andrea Gail, the Massachusetts fishing vessel that was lost in the Atlantic and memorialized in . But the Blue Heron has been retrofitted with state-of-the-art scientific instruments.

People wearing flotation devices who are submerged in water colder than 59 degrees have one minute to recover from the shock, ten minutes before losing effective use of their limbs, and one hour before losing consciousness.

“The good news is that the largest lake on earth is not too terribly messed up,” Robert Sterner, the observatory’s director, told me after we chugged under the 227-foot-tall Aerial Lift Bridge in Duluth and into the great steel blue expanse of water. “The bad news is that it is the fastest-warming lake on the planet.”

Sterner and a few fellow scientists were on the cruise to gather data to apply for a $6 million, six-year grant from the to do long-term ecological research. Also on the boat was Jay Austin, a physicist who earned his Ph.D. in oceanography at MIT and Woods Hole. His , shows that, while individual years vary, since 1980 Superior has been warming by an average of two degrees every decade. No one knows how that will change the lake and its ecosystem.

“We’re still going to see years of ice on the lake, but we’re going to see less of them,” Austin said. “We’re trying to improve our ability to predict what will happen as the lake gets warmer.”

It still feels invincible as it starts to toss Dahl and me around like a toy. After two hours, the current becomes so strong that Dahl decides not to pull up his second net. When we return to the marina, an old-timer fisherman named Royce is sitting in his truck, waiting for the daily report. He gives me a quizzical look and asks Dahl, “What did you catch out there, a mermaid?”

Like thousands of northern Minnesotans, my great-grandparents emigrated from Nordic countries in the late 1800s to fish, farm, and log. Minnesota and the larger lake region are famously ridiculed by nonlocals who love to crack Sven and Ole jokes. But one of the most refreshing traditions they brought with them is the sauna culture. Saunas are everywhere—in my sister’s Duluth backyard, on rocky outcrops behind lake cabins, and on Thompson Island, a provincial nature reserve, located 14 miles south of my next stop, for passing sailors and kayakers. Thunder Bay has the highest concentration of Finnish residents per capita in all of Canada. Sweating it out in a 200-degree wood-fired sauna is the best way to work up enough nerve to jump into Lake Superior.

The Canadian border is less than 200 miles from Duluth, but it has taken me three days to arrive. There are too many distractions: a break for a breaded whitefish sandwich and beer-battered fries at , and eight Minnesota state parks, with waterfalls as high as 120 feet and trails that feed into the 310-mile-long Superior Hiking Trail.

In Ontario, the vast emptiness of the lake’s coast sets in. In the 443 miles between Thunder Bay (population 108,359) and the eastern gateway city of Sault Ste. Marie (population 75,141), there is no town with more than 5,000 people.

“Looking into Lake Superior is like looking into the eye of God.”

Everything feels wilder here. The Sleeping Giant cliffs rise 1,200 feet straight out of the water on 32-mile-long Sibley Peninsula. To get a closer look, I hitch a ride with Gregory Héroux, owner of , on his 40-foot boat. A former amateur hockey player, Héroux trained three years on Lake Superior before he sailed out of Thunder Bay, across the Great Lakes, to the Atlantic, over to the Mediterranean, and back again.

“Lake Superior is known as the Everest of freshwater sailing,” he says. “You do something wrong out here and you’ll be cryogenically preserved.”

There’s a cool breeze that causes the boat to heel, and the vastness of the lake makes me feel about the size of a water molecule.

After camping, mountain biking, and hiking for a few days at , I drive 305 miles east to Wawa, a community that has been continuously occupied for at least 700 years. The original inhabitants were the Anishinabek, whose Ojibwe descendants still live here among the environmentally minded kayakers, biologists, and park employees. One resident is Joel Cooper. He retired years ago from the and lives with his wife, Carol Dersch, a naturalist for Lake Superior Provincial Park, in a log cabin with no indoor toilet that overlooks a beach.

“I’ve lived here for 35 years and do what I do out of sheer love and respect for the lake,” Cooper says. That includes prefabbing and installing ten “thunder boxes” along a 50-mile stretch of public land between Pukaskwa National Park and Wawa, so that passing kayakers will have a more comfortable and concentrated place to answer nature’s call. He also monitors peregrine falcons with his wife and volunteers to shuttle people in his 19-foot powerboat for that offers paddling expeditions along the whole Ontario coast.

Today the lake is glassy enough to water-ski as we speed past one beach after another on our way to the Dog River, a Class III–V whitewater playground that ends in 131-foot-high Denison Falls in Nimoosh, a roadless provincial park. Canadian canoeist Bill Mason filmed Waterwalker, the original 1980s whitewater film, on the river. “This type of recreation is for real introverts,” Cooper says. “Out here you’re on your own.”

Before I cross back into the U.S. through Sault Ste. Marie, I spend a night at Agawa Bay Campground in Lake Superior Provincial Park. The Trans-Canada Highway bisects the park, but it’s still beautiful, with aboriginal pictographs—such as the lynx-like creature the Ojibwe call the Spirit of the Waves—painted on a high cliff and a coastal trail that runs 40 miles along its 60-mile shoreline. The trail demands all my powers of concentration to pick my way through slippery boulders, deep sand, and smooth slabs of rock. In four hours I encounter no one. When I finally pitch my tent, the sky is a granite-colored smudge and a storm is brewing on the horizon. I’m excited to see it coming—after two weeks of unusually warm, placid weather, I’m ready for Lake Superior to unleash its rowdy side.

How long can Lake Superior remain so pure? I keep thinking about that question during the six hours it takes me to drive from Ontario to Whitefish Point, Michigan.

“This is some of the best and most strategic water on the planet,” John Downing, the director of the , part of a NOAA-funded network of college programs focused on marine research and education, told me on the Blue Heron. “Wars have been fought for thousands of years over water like this.”

In addition to climate change, threats to Lake Superior include the development of sulfide-ore copper mines in northeastern Minnesota, where a byproduct known as acid-mine drainage can contaminate lakes, rivers, groundwater, and everything living in them; proposed concentrated animal-feeding operations in Wisconsin, whose untreated liquid manure could run off into the lake; invasive species like zebra mussels that have infiltrated other Great Lakes bodies; and the prospect that arid U.S. regions might soon need Great Lakes water.

The lake has become like a security blanket, an assurance that humans haven’t yet tamed or destroyed everything wild.

To prevent this, in 2008, George W. Bush signed into law the Great Lakes Compact, part of a binational agreement between the eight Great Lakes states and two provinces. But exceptions have been made. Last July, Waukesha, Wisconsin, a Milwaukee suburb 17 miles west of Lake Michigan, became the first municipality outside the Great Lakes basin granted permission to divert water from a Great Lake. The town is allowed to take 8.2 million gallons per day from Lake Michigan, with the stipulation that it return the same quantity of treated water to the Root River, a tributary of the lake. There is concern that this could open the door for other towns and cities.

“We’re waiting to see if environmental organizations or neighboring communities are going to file suit,” says Peter Annin, author of, who lives on Lake Superior in Wisconsin. “The nightmare scenario would be that some climate-change-induced, long-term drought would lead to the country going for a run on Great Lakes water.” Hopefully, that’s a scenario that will never play out.

On the southern side of the lake, the deciduous trees, cliffy dunes, limestone outcrops, and sandy beaches feel almost gentle. But that’s a dangerous fallacy. From the top of Whitefish Point lighthouse, I can see the , the 80 miles of coastline that, thanks to heavier ship traffic, poor visibility, and storms that gather strength over nearly 250 miles of fetch, is the final resting place for more than 200 shipwrecks. Among them is the infamous Edmund Fitzgerald, a 729-foot freighter carrying 29,000 tons of taconite pellets that went down in a storm with 80-mile-per-hour wind gusts and 25-foot waves in 1975, killing all 29 sailors on board. Expert divers wearing drysuits can explore 30 well-preserved wrecks in the 376-square-mile .

One hundred and sixty miles west is the , which pokes 80 miles into the lake like a fat thumb. At its pinnacle in the mid-1880s, this peninsula produced 90 percent of the nation’s copper. These days it’s more and mountain biking. Copper Harbor, the former mining town at the tip, is , thanks to 35-plus miles of singletrack that climb 500 feet, an impressive elevation change for the Midwest. During one raucous festival over Labor Day, locals built a jump at the end of a dock that launched riders into the water.

The man largely responsible for the town’s renaissance is 48-year-old Sam Raymond, a former Colorado ski bum who spent summers here as a kid. “I got hooked on mountain biking in the nineties, but when I moved out to Colorado, I realized I missed Copper Harbor,” he says as we sit in Adirondack chairs in front of his . Raymond dug dirt and helped found a trails club that allowed Copper Harbor to eventually pay local trailbuilding guru Aaron Rogers to take care of the rest.

The singletrack here is fun and fast. On a Trek Fuel Ex 29er, I ride up the , avoid insane-looking jumps on , and finish off on , a curvy shot of perfectly bermed whoop-de-dos. Raymond credits the lake for Copper Harbor’s popularity.

“There’s a certain kind of energy here,” he says. “The big lake is like a magnet.”

I know what Raymond means. By the time I reach Bayfield, Wisconsin (population 746), I’ve traveled almost 1,300 miles and I’m 85 miles from home. The lake has become like a security blanket, an assurance that humans haven’t yet tamed or destroyed everything wild.

If Superior has a Riviera, Bayfield is it. The town anchors the and is full of rehabbed Victorians and streamlined yachts moored in its harbor. I decide it’s time for a little immersion therapy. The best way to do that is by kayak.

I’m chagrined that it’s taken me so many years to fully grasp the wonder of my own backyard.

Three miles north of Bayfield is owned by Gail Green and her husband, Grant Herman. Green spent years whitewater paddling in Sun Valley, Idaho, and photographing humpback whales in Hawaii. Herman has legendary boat-handling skills and practices water ballet in his canoe.

“Lake Superior isn’t easy,” Green says as she hands me a fresh apple-cider donut from a nearby orchard. “That’s what makes the reward so big.”

Our safety briefing includes a wet exit, which made one of my fellow kayakers, a nurse from Illinois, so nervous that it gave her heartburn. All six of us in the group pass the test, so we set out for two nights, paddling five miles toward Oak Island, a 5,078-acre forest that once had one of the highest densities of black bears in the region.

“It’s fucking beautiful out here,” says Victor Kasper, a former Marine from Milwaukee. The lake is warm enough—a relatively balmy 58 degrees, with air temperatures rising higher than 80—that we’ve stowed our wetsuits. We paddle past sandstone caves and a tugboat shipwreck, landing on a beach with time to set up tents and take iPhone time-lapse video of the sun dropping like an orange bomb. At dinner our guide, a Texan named Shane Walston who has paddled in Oman and Belize, cooks us flaky whitefish over a fire.

“Where I’m from,” Walston says, “most people couldn’t point out Lake Superior on a map. When I tell them I’m in Wisconsin, they ask why. It’s the people.”

As we set out for a 12-mile crossing the next morning, the lake is still dead calm, but the wind could whip into a frenzy at any moment. Miraculously, the water remains so placid that we cross in time to . We paddle through the maze, taking care not to touch the water-eroded arches, which look delicate enough to topple with the push of a finger.

On the return paddle, I eyeball the mainland and dread that I can almost see Duluth. I’ve been on the road 20 days, and I’m not ready to give up this ambulatory life of sleeping in my tent and stopping whenever the spirit moves me. I’m chagrined that it’s taken me so many years to fully grasp the wonder of my own backyard.

At dawn the next morning, I pad down to the beach and wade up to my waist. The chill creeps into my neck. I dive into the shallows and swim toward the flat horizon. The water feels so clean that I linger as long as I can in the cold, awake to the thrill that Lake Superior has finally let me in.

Contributing editor Stephanie Pearson () wrote about Swimmer Diana Nyad in May.