Right now, the outdoors is facing an unprecedented political attack. Efforts to halt climate change are being . Agencies that protect the environment are being . The Endangered Species Act may be “.” And efforts are underway to . There’s even talk of .

Why is this happening? In part because the oil and gas industries have bought off our politicians.

Rather than complain about the state of politics, work to be the change we believe in, or espouse some other well-meaning but ultimately ineffective slogan, why don’t we borrow a leaf from the Koch brothers’ playbook and buy our own politicians?

Oil Money Versus the Outdoors

Earlier this year, the outdoor recreation industry decided to seriously throw its political weight around for the first time. Politicians in Utah were threatening the places we play outdoors—they wanted to rescind the Bears Ears National Monument designation—so our biggest brands visited the state to remind legislators how much money they bring in and how many jobs they account for. Or more accurately: how much cash they could take with them if they left.

According to , “Outdoor recreation contributes more than $12 billion to the economy, employs more than 122,000 people, and is the primary driver behind the tourism industry. Not only does Utah outdoor recreation create $856 million in state and local tax revenues, it is the reason for $3.6 billion in wages and salaries.”

Oil and gas? Utah produces , and that industry .

One of the most visible symbols of the role outdoor recreation plays in Utah’s economy is the biannual Outdoor Retailer trade show. Each year, it brings 50,000 visitors and $45 million to Salt Lake City. Yet when leaders from Patagonia, The North Face, REI, and Outdoor Retailer called Utah Governor Gary Herbert to demand that he cease efforts to rescind the Bears Ears designation, he sided with oil and gas. In doing so, Herbert was prepared to let OR leave the state (which it did shortly thereafter).

Why? Money: . Private donations from individuals associated with that industry may have accounted for more.

Herbert is well known for blurring the lines between oversight of oil and gas in the state and his own political fundraising. For three years running, he has piggybacked a fundraising event on top of the state’s official Energy Development Summit, charging attendees $5,000 a table. Matt Pacenza, executive director of the Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah, has called the connection between the fundraiser and the summit “.”

There is no line item for outdoor recreation in Herbert’s campaign disclosure, but he did receive $19,000 from Recreation and Live Entertainment and $8,000 from Lodging and Tourism, which share some of our interests, particularly in Utah. I wonder if that phone call with Outdoor Retailer and its leading brands would have gone differently if they had been lining his pockets with as much cash as oil and gas?

The financial connection between oil and gas money and policy is even clearer with another Utah politician. �����Ƿ�, . In January, Bishop stated that he “would love to invalidate [the ESA].” Why? “It’s been used for control of the land.” The industry that would like to gain access to land currently off-limits due to the ESA? Oil and gas.

How the Outdoors Lobbies Now

It’s important to realize that our industry is currently engaged in significant and successful efforts to lobby for our interests. But it’s also important to understand that those efforts, along with our industry, are fairly young and still evolving.

I spoke with Amy Roberts, executive director of the , who detailed our industry’s lobbying efforts in Washington. The OIA is a trade organization that lobbies for the interests of members like Birkenstock, Big Agnes, and even giant companies like REI, but also includes tiny specialty gear brands and mom-and pop-retailers with only a single storefront.

“For the industry as a whole, we’ve had a PAC since 2008,” explains Roberts. The OIA uses campaign donations from that PAC to try to influence policy on topics like public lands and the environment, as well as trade policies that are important to its members. That means the PAC donates to both Democrat and Republican candidates, Roberts says, and focuses exclusively on candidates running for federal office.

Those donations buy the OIA access. Once the offices of a politician are paying attention, the OIA meets with staff to “discuss the nitty-gritty of policy,” Roberts says. When OIA gets a meeting with a member of Congress, the group’s strategy is to bring along executives of companies from their districts—constituents, in other words.

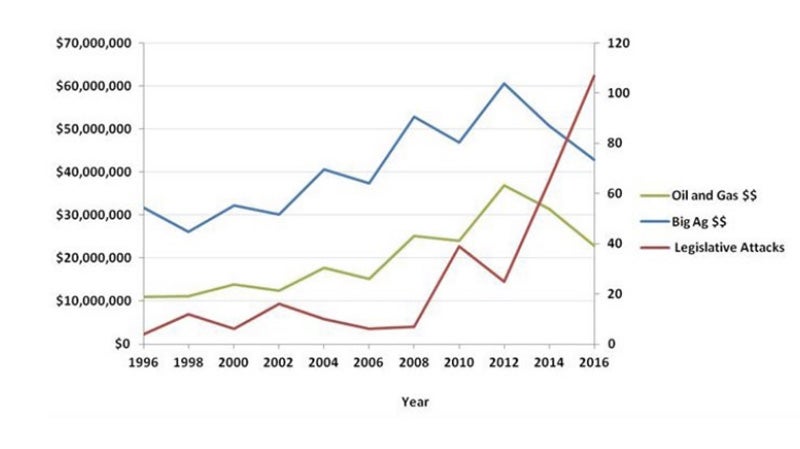

So far, this sounds exactly like the lobbying strategy of oil and gas. Campaign donations are used not only to help like-minded politicians get elected, but also to buy access to discuss policy and demonstrate its benefits back home. Trouble is, the difference between the amount of money spent by the OIA versus oil and gas is huge. The OIA’s PAC spends about $50,000 per election cycle, across all its donations, says Roberts. Last year, oil and gas PACs donated three times that amount to Rob Bishop alone.

Despite that disparity, we do still have a voice in Washington. “We’re seen as a fun industry,” says Roberts. “We have a halo.” She says the OIA doesn’t have trouble getting meetings, despite the small amount it’s able to donate. “Where I think we’ve had the most success over the last decade is how we’ve been able to talk about the power of the outdoor recreation economy,” Roberts explains. She’s talking about the outdoor recreation industry’s , a figure you’ve likely seen bandied about in articles about public lands and politics for the past few years.

One of the OIA’s biggest successes was last year’s Outdoor Recreation Jobs and Economic Impact Act. It authorizes the Department of Commerce to measure the industry’s contribution to the gross domestic product and will allow us to break down those jobs and dollars by congressional district. It’s widely believed that the results, coming in 2018, will bring the outdoor recreation industry out of the shadows and into the mainstream by verifying just how much we generate in consumer spending. If that $646 billion number is accurate, it would make outdoor recreation the third-largest source of consumer spending in the United States, behind only healthcare and financial services. Oil and gas only accounts for $354 billion a year.

But attention doesn’t buy policy.

Where Outdoors Lobbying Is Going

If the industry is so big, why don’t we have a bigger voice in politics and the funds to buy it?

“Wealth is very much consolidated in oil and gas, and we don’t have many wealthy tycoons in outdoor recreation,” explains Cam Brensinger, founder of Nemo Equipment. Nemo is an OIA member, and Brensinger has been visiting Washington to lobby lawmakers with that company for nearly a decade. Brensinger is 40 years old, and the company he started is 15. Both are successful, but they’re not (yet) at the point where they have congressmen in their pockets.

“If you look at the founders of the iconic outdoor companies, they’re just now getting to retirement age,” says Roberts. “Our industry is just one or two generations old at this point. We are less entrenched in Washington.”

(CA) was founded in 1989 by REI, Patagonia, The North Face, and Kelty to fund grassroots conservation efforts. Today, it boasts more than 200 member companies that donate a portion of their earnings. Kate Ketscheck, a member of the CA board, tells me, “[The Conservation Alliance] has contributed $17 million since 1989, saving 50 million acres of wildlands, protecting nearly 3,000 miles of rivers, halting or removing 29 dams, designating five marine reserves, and purchasing 12 climbing areas.”

In November, the CA recognized the political threat to public lands and voted to create a Public Lands Defense Fund. It will work to defend “bedrock conservation laws” like the Antiquities Act, preserve previous national monument designations, and prevent the transfer of public lands to state or private hands. The fund has received an initial financial commitment from The North Face and Patagonia to the tune of $100,000 per year for the next three years.

The fund doesn’t operate its own programs, but instead grants money to organizations working to protect public lands. The CA but does not currently give you the ability to direct your donation toward a specific program like the Public Lands Defense Fund. It’s also almost entirely funded by its member companies, but Ketschek tells me they’re working on a program to enable member companies to educate their customers about the CA and the work it does. One hundred percent of funds raised by the CA go to its grants.

So far, no one has presented the Public Lands Defense Fund with a plan to buy a politician.

How to Buy a Congressman

In 2006, he pleaded guilty to felony counts of lobbying-related conspiracy, fraud, and tax evasion; served four years in prison; and was fined more than $20 million. The scandal also brought down a congressman from Ohio, along with many staff and other political types. Abramoff is the living embodiment of corruption in politics. And, man, was he good at it.

According to Abramoff, “The whole system is corrupt.” And buying politicians is pretty easy. Abramoff describes it as a widespread activity, one that hasn’t been diminished by reforms enacted after his downfall. “It hasn’t been cleaned up at all,” he told interviewer Lesley Stahl.

In the interview, Abramoff lays out a simple three-step plan for buying a congressperson:

1. Offer jobs to their staff. “When we would become friendly with an office and they were important to us, and the chief of staff was a competent person, I would say or my staff would say to him or her at some point, ‘You know, when you’re done working on the Hill, we’d very much like you to consider coming to work for us.’ Now, the moment I said that to them or any of our staff said that to ’em, that was it. We owned them. And what does that mean? Every request from our office, every request of our clients, everything that we want, they’re gonna do. And not only that, they’re gonna think of things we can’t think of to do.”

2. Pay for leisure activities. “I spent over a million dollars a year on tickets to sporting events and concerts and whatnot at all the venues. I had two people on my staff whose virtual full-time job was booking tickets. We were Ticketmaster for these guys.”

3. Organize fundraisers. “You can’t take a congressman to lunch for $25 and buy him a steak. But you can take him to a fundraising lunch, and not only buy him that steak, but give him $25,000 extra, and call it a fundraiser.”

Together, that approach enabled Abramoff to draft language for his client companies and have it directly introduced into bills. He estimates that he had that ability with “over 100” of our elected representatives.

Let’s Buy a Congressman!

If buying a congressman is so easy, and if buying congressmen (and other politicians) is what nets oil and gas victories over our interests even though we have the moral and economic high ground, then why aren’t we buying our very own congressmen? Let’s look at Abramoff’s methods and figure out how they could translate to the outdoor recreation industry.

1. Offer jobs to congressional staff. This should be easy. Who wouldn’t want to work for an outdoors company? It’s true that we probably couldn’t match the salaries of a high-powered lobbying firm, but think of the benefits.

2. Pay for leisure activities. Again, easy. Abramoff offered congressmen all-expenses-paid skyboxes for them and “up to two dozen” of their friends at Redskins games. Football is boring—how about a whitewater rafting trip? Heck, former congressional aides turned professional river guides could even bend politicians’ ears about policy as they’re experiencing an endorphin high after swimming a Class V.

The OIA’s Roberts is candid about our industry’s appeal. She’s able to get meetings despite her tiny budget specifically because people love the outdoors and the athletes outdoor brands sponsor. Abramoff describes his staff as “like Ticketmaster.” Could the outdoor recreation industry be like travel agents for politicians?

3. Organize fundraisers. This is where it gets serious. Everyone who works in this industry is passionate about the outdoors and its causes. And there are 6.1 million of us. Many of us already donate money to wildlife charities and political campaigns. And yet there’s no cohesive program to apply our collective cash to achieving our collective political goals.

Like oil and gas, or any other big, politically entrenched industry, there’s no reason our money couldn’t buy us the ability to have our own language introduced in congressional bills and to ensure that members of that organization vote in our favor.

It’s All About the Benjamins

On April 21, 2016, Bernie Sanders achieved the impossible. Targeting individual donors contributing an average of $27, he raised as much money for his primary campaign as his establishment rival—. Could a similar campaign of grassroots donations be used to give the outdoors the political clout (read: budget) it needs?

“You can’t completely ignore the fact that you have to participate in the political process,” Roberts tells me. “And that involves supporting candidates who share your values. Those other industries definitely have larger war chests than we do.” Roberts says the OIA is planning to pursue more grassroots funding. “I think that’s where we have a lot of opportunity,” she tells me.

So how do we get a larger war chest to influence policy around public lands, the environment, wild animals, and all that stuff that’s so essential to our lives? Let’s pull out a napkin and scribble down some numbers.

REI has demonstrated a willingness to put its money where its mouth is and fund public lands defense. REI is owned by its members, who pay $20 to join and who must spend more than $10 on a regularly priced purchase. Those members receive an annual dividend for 10 percent of what they spent on regularly priced purchases in the previous year. REI has and .

Those dividends arrive in the form of a gift card. I got mine in the mail a week ago and have already lost it. It was for a little less then $27. I would have happily ticked a box for 100 percent of my dividend to go to the Conservation Alliance’s Public Lands Defense Fund. I would happily make that payment recurring, every year, forever. An informal survey of the REI members currently present in my house (three) suggests that they would happily do the same.

My point here isn’t to pick on REI. It’s to demonstrate that our industry has ample funding sources available to achieve the political goals that have suddenly become so important to our future. All it would take is setting up the ability for all of us to participate in them and educating us about the ability to do so. Bernie did it, and we can, too. We just recreate his campaign’s fundraising structure.

Once that money starts flowing, we need to stop being precious about how it’s spent. There will be a time when ethical, moral people run politics in Washington. That time is not now. We clearly understand how oil and gas beats us. With outdoor recreation’s sheer numbers, there’s no reason we can’t start winning, too. It’s time the outdoors starts fighting dirty.