On October 5, 1999, an avalanche high on the slopes of Tibet’s 26,289-foot Shishapangma swept down the mountain’s south face, killing Bozeman, Montana’s Alex Lowe—then 40 and easily the best all-around mountaineer of his generation—and expedition cameraman and rising star David Bridges, 29, of Aspen, Colorado.

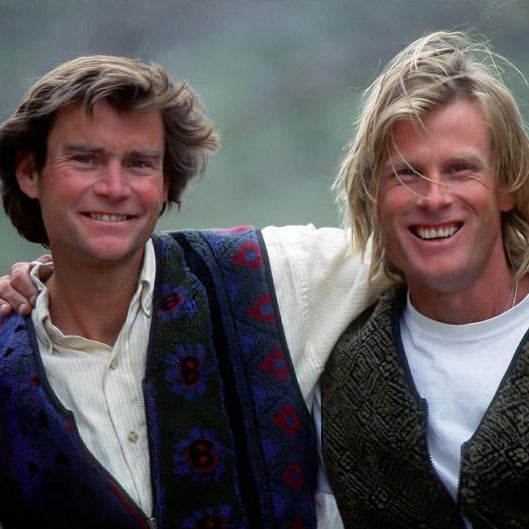

Lowe, Bridges, and Conrad Anker—Lowe’s best friend and regular climbing partner—were leading a reconnaissance hike to scope out the couloir they hoped to ski from the mountain’s summit, an objective that would have made their nine-man expedition the first by Americans to ski an 8,000-meter peak.

As the avalanche struck, Anker ran to the left while Bridges and Lowe ran downhill and right. Anker was partially buried and had a rib snapped and his head gashed open by the ice projectiles that hit him. But he could walk. Below him, in a group that was bringing up the rear, Utah skiers Andrew McLean and Mark Holbrook, along with Bozeman skiers Hans Saari (who died two years later in a ski accident in Chamonix, France) and Kristoffer Erickson*, avoided the avalanche. With Anker, they spent the next two days searching for any sign of Lowe and Bridges. They didn’t find so much as a glove.

“From my perspective there was just this big white cloud, and then it settled and there was nothing there,” Anker recalled during a phone interview from Bozeman, where he and Jennie landed on April 29 after spending the spring in Nepal. “And it was just so massive and so big. There wasn’t that sense of closure.”

Anker began helping Lowe’s widow Jenni to raise their three boys, Max, Isaac, and Sam, back in Bozeman. The two, in their shared grief, soon fell in love and were married in 2001. That story was the subject of by Jenni Lowe-Anker and chronicled in the documentary Meru, which played in theaters across the U.S. last year and made the short list for the 2016 Oscars.

But now Lowe’s death appears to have a final resolution. Last week, on April 27, some 16 years, 6 months, and 22 days after their disappearance, the bodies of Lowe and Bridges were found by Swiss and German alpinists Ueli Steck, 39, and David Goettler, 37. The two partners are attempting to climb a new route up Shishapangma’s south face this spring.

“It’s kind of fitting that it’s professional climbers who found him,” Anker says. “It wasn’t a yak herder. It wasn’t a trekker. David and Ueli are both cut from the same cloth as Alex and me.”

“I kind of never realized how quickly it would be that he’d melt out,” says Jenni Lowe-Anker. “I thought it might not be in my lifetime.”

Anker and Jenni Lowe-Anker had spent much of the spring in the Khumbu region of Nepal working on the Khumbu Climbing Center (KCC), a project of the . They’d missed Steck and Goettler by a day as the two alpinists acclimatized in the Khumbu before heading over to Chinese-controlled Tibet for their climb. (Shishapangma, the world’s 14th-highest mountain, is the only 8,000-meter peak that sits completely inside Tibet.) As Conrad and Jenni were preparing to fly home to Bozeman on the 27th, Anker’s phone rang. It was Goettler, attempting to confirm the identity of the two bodies they’d discovered partially melting out of the glacier.

“He said, We came across two bodies,” says Anker. “They were close to each other. Blue and red North Face backpacks. Yellow Koflach boots. It was all that gear from that time period. They were pretty much the only two climbers who were there.”

Anker hasn’t seen photos, and there hasn’t been a conclusive test, but he’s already convinced. “We’re pretty sure it’s them,” he says.

Unlike the remains of climbers that are sometimes found high on Everest, the bodies of Lowe and Bridges are in a place where they can be recovered. (The body of guide Scott Fischer, a casualty of the 1996 storm on Everest that spawned Into Thin Air, remains on the mountain in line with the wishes of his family.)

Conrad, Jenni, and the three boys, now grown, are now planning to travel to Tibet during the summer monsoon. They’ll recover the bodies (they haven’t yet been in touch with Bridges’s family) and most likely return to Nyalam, Tibet, the closest town, to hold a ceremony.

“The proper thing to do will be to take care of his body according to local practices,” says Anker. “They’re still frozen into the ice.”

“It’s never something you look forward to,” says Jenni. “To see the body of somebody you loved and cared about. But there is a sense that we can put him to rest, and he’s not just disappeared now.”

This spring, like the last three, has been exceptionally warm and dry in the Himalayas. The increasingly common wind storms that deposit heat-absorbing dust on the glaciers have sped up melting even more. Everest Base Camp, at the head of the Khumbu Glacier in Nepal, has seen running streams and climbers relaxing in shorts and flip-flops, something that usually doesn’t happen until May. That’s one possible explanation for why the bodies could have melted out so quickly.

For Conrad and Jenni, the event seemed to have added significance, given the recent events in Nepal. “Whether it’s fate or coincidence or timing, you never know,” says Conrad. “The Khumbu is still bereft of tourists, and people in Nepal are still suffering,” says Jenni. “The people there are still so hopeful that there’ll be a good season on Everest and that tourism will return. For us to be up there was a bright spot for them and for us. Conrad made an appearance at Base Camp, and that was meaningful to them and all the people that have worked with us on KCC. And then to have [Alex found on] the very last day. … I thought that was kind of serendipitous. It was like Alex appearing in a way to say, Hey, good work. I’m done. I’m done now.”

*Update: An earlier version of this story misspelled Kristoffer Ericsson's name.